There once was a young man at Nunhead,

Who woke in a coffin of lead;

“It is cosy enough,”

He remarked in a buff,

“But I wasn’t aware I was dead.”

The Perils of Premature Burial (1905)

Cemeteries gain a reputation for being haunted for reasons that include premature burial, desecrations of corpses, unmarked graves, grave robbers, disturbance of plots and other disasters.

During the nineteenth century, Taphophobia- the fear of being buried alive- was quite common, and it was tragically justified. Far too many people lived with an abiding fear of being mistaken for dead and waking trapped in a coffin, six feet below the ground.

To be buried alive is, beyond question, the most terrific of these extremes which has ever fallen to the lot of mere mortality… the boundaries which divide Life from Death, are at the best shadowy and vague. Who shall say when one ends and the other begins?

Edgar, Allan Poe, The Premature Burial

Stories and accounts fueled the public imagination and made for scandalous and chilling reading material. ‘Bloods’ or ‘Penny Dreadfuls’ featured tales of human combustion, murder, torture and cannibals. Another popular subject was premature burial, described in hideous detail.

The uncertainty of the signs of death was once a source of emotional suffering. Stories about being accidentally buried alive dated back centuries. In 1308, a man named Johannes Duns Scobus was mistakenly thought to be dead and was interred in his tomb. When the crypt was later reopened, Scotus was found outside of his coffin. HIs hands were torn and covered with blood from his futile effort to escape the grave.

In 17th century England, it is documented that a woman by the name of Alice Blunden was buried alive. As the story goes, she was so knocked out after having imbibed a large quantity of poppy tea that a doctor holding a mirror to her nose and mouth pronounced her dead. (Tea made from dried, unwashed seed pods would have contained morphine and codeine, which are sedatives.) Her family quickly made arrangements for her burial, but two days after she was laid in the ground, children playing near her grave heard noises. Their school master went to check the gravesite for himself. He found that Blunden was still alive, but it took another day to exhume her. She was so close to death that she was returned to her grave, where a guard stood by before deserting his post. The next morning, she was found dead, but only after struggling to free herself once more.

The ‘Lady With The Ring’ is a story about premature burial popular across Europe. Versions of the story have been found to exist in almost every European country, including Germany, the Netherlands, France, Scandinavia, Italy, England, Scotland, and Ireland. The story is also told about a former resident of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, Canada.

The most famous version of the story is from Cologne, where the woman has been popularly identified as Richmodis von Aducht, the wife of Menginus von Aducht. The incident was said to have occurred during the Black Death in 1357, though other versions claimed that it occurred in the 16th century. In Richmodstraße in Cologne one can find "Richmodis House", birthplace of the composer Max Bruch, where—according to legend—the Aduchts had lived. From a tower two sculpted horseheads look out of a window. These heads by sculptor Wilhelm Müller-Maus were installed in 1958 as a replacement for the wooden ones by Christoph Stephan (1797–1864) that had not survived the bombings of WWII.

In 1920, an ethnologist determined that there were nineteen cities in Germany that claimed that a version of the Lady of the Ring had occurred there, including Hamburg, Dresden, Freiberg and Lübeck. In eleven of the cases, there were horse sculptures that commemorated the strange ending to the story.

The signs of death have always been discussed in medical writings. Not, however, until the 1740s in France were the comments of the ancients and recent physicians, assimilated into a debate over the certainty of the signs of death. In 1742, a distinguished French doctor named Jacques Benigne Winslow wrote his book ‘The Uncertainty of the Signs of Death.’ It was a book that examined the medical professionals' difficulty in recognising signs of death which often resulted in medical ailments of patients presenting to a doctor as someone deceased and thus a patient could find themselves pronounced dead too early. It was an experience Winslow himself was all too familiar with given he had been declared dead and placed in a coffin not once- but twice prematurely as a child. Winslow’s work was translated from Latin to French by his student Bruhier. The famous French surgeon Louis also published important works during this period on the subject of the signs of death which were produced in Latin, French, German, English, Italian and Spanish.

Eddowe’s Journal of August 1844, tells of a child who was accidentally buried alive. While the sexton was filling in the grave, he was startled to hear the boy calling for help. Quickly the coffin was uncovered and the boy was rescued. The boy thankfully made a full recovery but the account finished on a sombre note recalling, “not long ago, in making a grave in the same cemetery, a coffin was broken into, and it was found that the occupant had revived after burial, and had gnawed the flesh of both wrists before life was finally extinguished.”

William Tebb’s Premature Burial and How It May Be Prevented, With Special Reference to Trance, Catalepsy, and Other Forms of Suspended Animation, published in 1896 was more than 500 pages in length. Owing to “a distressing experience” in his family, Tebb dedicated himself to stamping out the scourge of premature burial and other “death-counterfeits”; “the danger,” he wrote, “is very real.” By his estimate, in England and Wales alone some twenty-seven hundred people were annually “consigned to a living death.” A stern epigraph from Professor Alexander Wilder drives this point home: “The thought of suffocation in a coffin is more terrible than that of torture on the rack, or burning at the stake … When we neglect precautions against a fate so terrible, our tears are little less than hypocrisy and our mourning is a mockery.”

The book’s most gripping sections are given over to accounts of internment gone awry, along with the many anxieties of the nineteenth-century deathbed. There’s the man who sank into such a prolonged lethargy that he was thought dead until he “broke into a profuse sweat” in his coffin; the young woman whose corpse was exhumed for reburial only to be discovered “in the middle of the vault, with dishevelled hair and the linen torn to pieces … gnawed in her agony”; the man whose fear of premature burial was so severe that he instructed his family to leave his body undisturbed for ten days after death, “with the face uncovered, and watched night and day. Bells were to be fastened to his feet. And at the end of the second day veins were to be opened in the arm and leg.”

Tebb draws some of his most abject cases, fittingly enough, from The Undertakers’ and Funeral Directors’ Journal, a veritable storehouse of medical malfeasance. The Journal ran at least one story of a pregnant woman who gave birth in the grave. It also has an episode with one of the only happy endings in the whole book:

“Mrs. Lockhart, of Birkhill, who died in 1825, used to relate to her grandchildren the following anecdote of her ancestor, Sir William Lindsay, of Covington, towards the close of the seventeenth century:—‘Sir William was a humorist and noted, moreover, for preserving the picturesque appendage of a beard at a period when the fashion had long passed away. He had been extremely ill, and life was at last supposed to be extinct, though, as it afterwards turned out, he was merely in a “dead faint” or trance. The female relatives were assembled for the “chesting”—the act of putting a corpse into a coffin, with the entertainment given on such melancholy occasions—in a lighted chamber in the old tower of Covington, where the “bearded knight” lay stretched upon his bier. But when the servants were about to enter to assist at the ceremonies, Isabella Somerville, Sir William’s great-granddaughter, and Mrs. Lockhart’s grandmother, then a child, creeping close to her mother, whispered into her ear, “The beard is wagging! the beard is wagging!” Mrs. Somerville, upon this, looked to the bier, and observing indications of life in the ancient knight, made the company retire, and Sir William soon came out of his faint. Hot bottles were applied and cordials administered, and in the course of the evening he was able to converse with his family. They explained that they had believed him to be actually dead, and that arrangements had even been made for his funeral. In answer to the question, “Have the folks been warned?” (i.e., invited to the funeral) he was told that they had—that the funeral day had been fixed, an ox slain, and other preparations made for entertaining the company. Sir William then said, “All is as it should be; keep it a dead secret that I am in life, and let the folks come.” His wishes were complied with, and the company assembled for the burial at the appointed time. After some delay, occasioned by the non-arrival of the clergyman, as was supposed, and which afforded an opportunity of discussing the merits of the deceased, the door suddenly opened, when, to their surprise and terror, in stepped the knight himself, pale in countenance and dressed in black, leaning on the arm of the minister of the parish of Covington. Having quieted their alarm and explained matters, he called upon the clergyman to conduct an act of devotion, which included thanksgiving for his recovery and escape from being buried alive. This done, the dinner succeeded.’”

In 1849, a severe cholera epidemic killed 199 people. An older woman who oversaw the cholera wards stated that as soon as patients died, they were placed into wooden coffins, and the lids screwed down. They were then moved outside into a small shed so that would be out of the way. She later told authors William Tebb and Edward Vollum, that sometimes, “they’d come to afterwards, and we'd hear them kicking in their coffins, but we never unscrewed them, because we knew they had to die.”

The Lancet, November 27, 1858, p. 561, cites a remarkable case which was afterwards corroborated in all its details by the surgeon who attended the patient, Mr R. B. Mason, M.R.C.S., of Nuneaton.

“The girl, whose name is Amelia Hinks, is twelve or thirteen years of age, and resides with her parents in Bridge Street, Nuneaton. She had lately appeared to be sinking under the influence of some ill-explained disorder, and about three weeks since, as her friends imagined, she died. The body was removed to another room. It was rigid and icy cold. It was washed and laid out with all due funereal train. The limbs were decently placed, the eyelids closed and penny-pieces laid over them. The coffin was ordered. For more than forty-eight hours the supposed corpse lay beneath the winding-sheet, when it happened that her grand-father, coming from Leamington to assist in the last mournful ceremonies, went to see the corpse. The old man removed a penny-piece, and he thought that the corpse winked! There was a convulsive movement of the lid. This greatly disturbed his composure; for, though he had heard that she died with her eyes open, he was unprepared for this palpebral signal of her good understanding with death. A surgeon is said to have been summoned, who at first treated the matter as a delusion, but subsequently ascertained stethoscopically that there was still slight cardiac pulsation. The body was then removed to a warm room, and gradually the returning signs of animation became unequivocal. When speech was restored, the girl described many things which had taken place since her supposed death. She knew who had closed her eyes and placed the coppers thereon. She also heard the order given for her coffin, and could repeat the various remarks made over her as she lay in her death-clothes. She refused food, though in a state of extreme debility. She has since shown symptoms of mania, and is now said to have relapsed into a semi-cataleptic condition.”

In July 1889, a particularly gruesome case was recounted in ‘Undertaker’s Journal and Funeral Directors’ Review.’ The article recalled a New York case from 1854 in which a baker placed the coffin of his deceased daughter in a temporary vault, so that the girl’s older sister had time to arrive for the funeral from St. Louis. This was testified to by an undertaker who had performed the service who had stated that preservation of the body was possible given her death had taken place in winter and the cold wintry temperatures of the season would prevent severe decomposition. When the sister finally arrived for the service, the vault was once again opened for the funeral and the lid of the coffin removed. Inside lay a grim discovery. Buried alive, the young girl had torn her clothes to shreds and the ends of several of her fingernails had been torn away as she tried to claw her way out of the wooden coffin.

Physician Franz Hartmann, published a book called ‘Premature Burial’ in 1895 in which he had collected over 750 cases of people being buried alive. It was a book universally condemned by other doctors from the medical profession who feared the public’s response.

The Daily Express, of March 20, 1903, and the Daily Mail, of the 9th, give details of the supposed death of a well-known lady, who, with her family, had long resided in the village of Woore, near Keele, North Staffordshire, and who, after having been certified as dead by the local physician, was laid ready for interment:

“All preparations for the funeral had been made, and friends and relatives assembled to take a final farewell. As the mourners watched, the eyes of the lady were seen to open and her lips to move. Life had returned to the supposed corpse. The news of the strange event spread throughout the village and district, and produced the greatest excitement.”

The London Globe, October 26, 1896, mentions the following case:

“A soldier’s wife was reported by a military surgeon to have died during her confinement. She was buried on his certificate of death; but about two days afterwards the baby to whom she had given birth was also reported dead. The mother’s coffin was then disinterred and opened, with the view of placing the deceased baby in it; but, horrible to relate, it was discovered by only too evident signs that the woman had been buried alive, and had recovered consciousness after burial.”

The Undertakers’ Journal, November 22, 1880, relates the following:

“An extraordinary story is reported from Tredegar, South Wales. A man was buried at Cefn Golan Cemetery, and it is alleged that some of those who took part in carrying the body to the burial-ground heard knocking inside the coffin. No notice was taken of the affair at the time, but it has now come up again, and the rumour has caused a painful sensation throughout the district. It is stated that application has been made to the Home Secretary for permission to exhume the body.”

Author Rodney Davies, who sadly passed away in 2023 wrote in his book The Lazarus Syndrome accounts of a London cemetery damaged by a German bomber during WWII which unearthed coffins and bodies that exhibited signs of having been buried alive. Fingernails split, broken or town away; skin damaged; fists clutching town clothing in their hands.

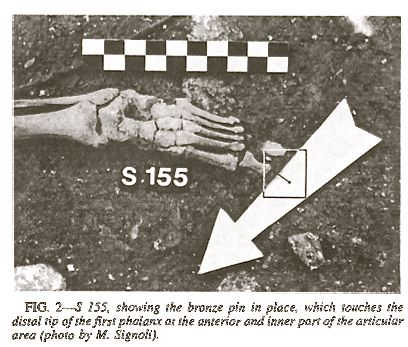

Beginning in the eighteenth century, medical literature on the signs of death reveals physicians’ knowledge of the signs, disagreement about them, and professional insecurity. To prevent two frightening possibilities- premature burial, and premature cessation of medical intervention- eighteenth and nineteenth century physicians proposed a variety of safeguards: legislation, mortuaries, mechanical devices, Humane Societies, and the presence of a physician at the time of death. Fear of premature burial created an exhaustive list of tests and measures to check for death. It was accepted that corpses would fear no pain and so therefore methods of inflicting pain on the corpse was used to see if the person would wake up. Evidence obtained for one method used in the verification of death during the Great Plague of Marseilles in 1722 was gathered during the excavation of a mass grave dating from this epidemic, and is based on two adjacent interments. The technique used at that time was the implantation of bronze pins into the toes post mortem. This method is precisely described in the medical treatises dating from this period, which list different death verification methods. The fear of "false death" and the burial of still living people characterised the end of the 17th and the 18th centuries. This discovery was the first anthropological evidence of the use of this forensic method to verify the fact of death.

Jean Jacques Winslow hoped to discover a definitive surgical test. He concluded that pinpricks and incisions were helpful but inconclusive. His student Bruhier drew a more radical conclusion: all signs of death, except for putrefaction, were inconclusive. Bruhier insisted that the corpse be dissected, embalmed, or buried only after putrefaction. This approach known as the ‘uncertainty thesis’ posed great dangers during times of war, epidemic or civil disorder when it was difficult to wait for putrefaction

A doctor named Josat invented a pair of sharp forceps that were used to pinch the nipples or tongue of someone thought to be dead.

Tobacco smoke enemas were commonly employed in 18th-century Europe to try to resuscitate the apparently dead. Smoke—blown through a pipe into the rectum using a bellows or from the mouth of an unflinching rescuer—was thought to bring people back from the brink of death. Drowning victims were subjected to smoke enemas after being hauled from the water, with occasional, and coincidental, success.

There were a series of inventions in the 19th century, which would aid someone, who was buried alive, to escape, breathe and signal for help.

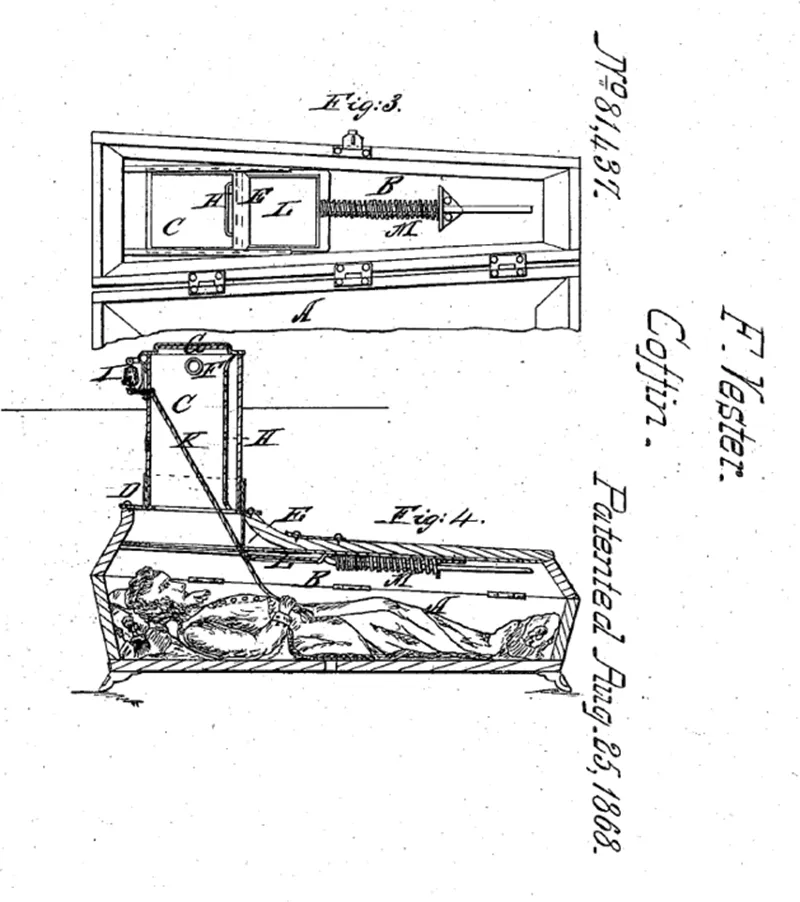

Patent No. 81,437 granted to Franz Vester on August 25, 1868 for an “Improved Burial-Case”

The tomb is equipped with a number of features including an air inlet (F), a ladder (H) and a bell (I) so that the person, upon waking, could save himself. “If too weak to ascend by the ladder, he can ring the bell, giving the desired alarm for help, and thus save himself from premature death by being buried alive,” the patent explains.

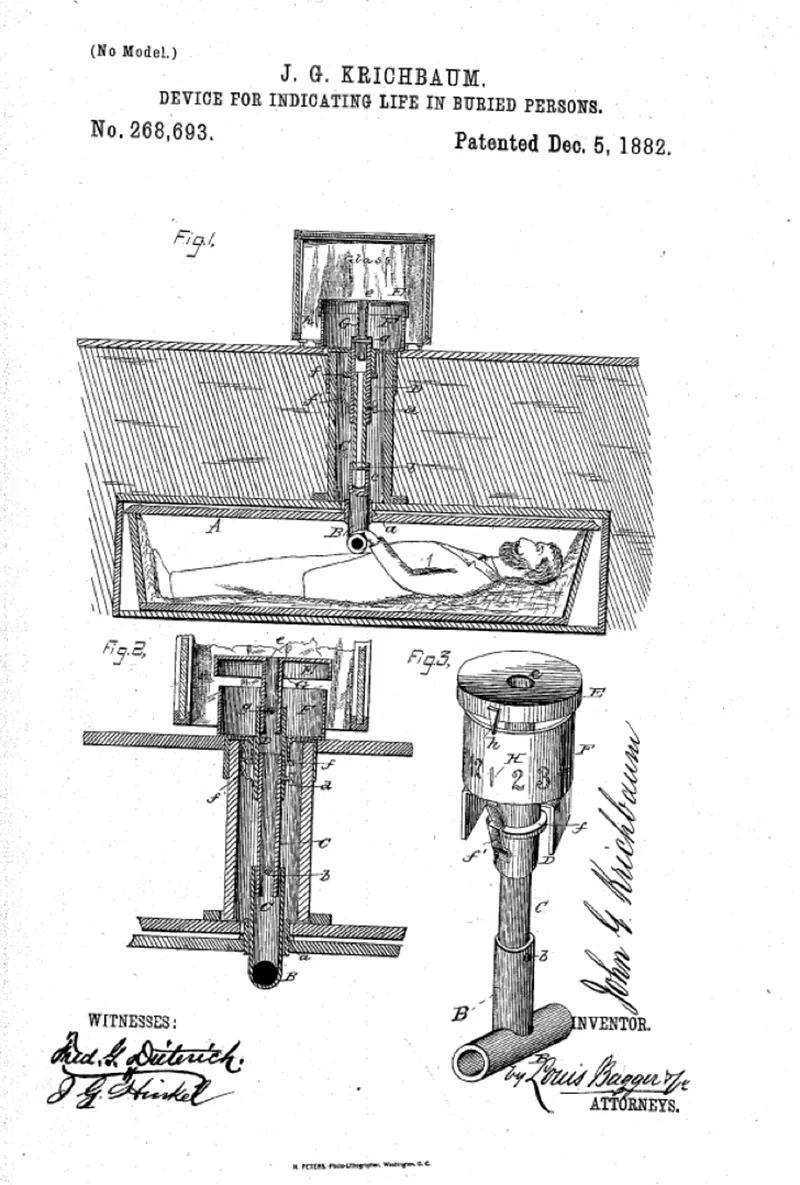

Patent No. 268,693 granted on December 5, 1882 to John Krichbaum for a “Device for Indicating Live in Buried Persons”

The device has both a means for indicating movement as well as a way of getting fresh air into the coffin. The disclosure states that “It will be seen that if the person buried should come to life a motion of his hands will turn the branches of the T-shaped pipe B, upon or near which his hands are placed.” A marked scale on the side of the top (E) indicates movement of the T, and air passively comes down the pipe. Once sufficient time has passed to assure that the person is dead, the device can be removed.

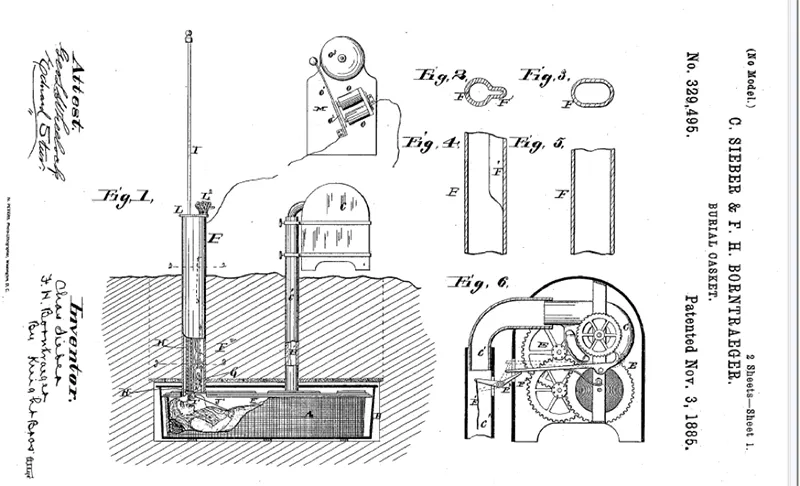

Patent No. 329,495 granted on November 3, 1885 to Charles Sieler and Fredrerick Borntraeger for a “Burial-Casket”

The invention provides for improvements in the important components of previous “buried alive” inventions. In this instance, motion of the body triggers a clockwork-driven fan (Fig. 6), which will force fresh breathable air into the coffin instead of a passive air pipe. The device also includes a battery-powered alarm (M). According to the patent, “When the hand is moved the exposed part of the the wire will come in contact with the body, completing the circuit between the alarm and the ground to the body in the coffin,” the alarm will sound. There is also a spring-loaded rod (I), which will raise up carrying feathers or other signals. Additionally, a tube (E) is positioned over the face of the buried body so that a lamp may be introduced down the tube and “a person looking down through the tube can see the face of the body in the coffin.”

Safety coffins addressed the primal fear of premature burial by incorporating design features such as air tubes, strings linking the body’s hands and feet to an above-ground bell, flag or lights and, for coffins installed in vaults, spring-loaded lids. Despite the rash of patents and production, there are no reported cases of the left-for-dead being saved by such contraptions.