Death Omens Of Ireland by Aoife Sutton-Butler

‘Long ago the Banshee was heard crying. She cries for a lot of families’: The Death Omens of Ireland.

Ireland has been an island long associated with stories of death, traditions, and folklore. As far back as primary school, children are told everything about the Banshee and her screams. Many still attend traditional Irish wakes of loved ones, interacting with the dead body itself as part of the bereavement process. Death is an important part of Irish heritage and identity. In Dr Marie Cassidy’s book Beyond the Tape: The Life and Many Deaths of a State Pathologist - memoir which recounts her years as Ireland’s State Pathologist between 2004 and 2018, one statement in her book stands out. ‘The Irish are obsessed with death’, Cassidy states. She goes on to say that attending funerals in Ireland is a national sport and instead of checking your horoscope, the Irish listen to the death notices on the radio - this conjures up so many memories from the author’s own childhood. The Irish feeling comfortable with death has often been linked with the history and tradition of the island, including stories of folklore and mythology. Traditions and stories may have been implemented in Irish culture as a way to deal with the loss of a loved one, or as a way to manage the fear of dying, particularly in a time before the widespread availability of modern medicine. Today, Irish people still often bring their loved one home to their house after their death, allowing them to be waked at home. They still draw the curtains and put black on the door in the house where the deceased rests. Coffins are still anointed in holy water and cleansed with incense – we still go through the traditional rituals of death in a society when alternative death plans are on the rise and becoming more widespread.

Premonitions of death are strongly associated with Irish folklore. Using the National Folklore Collection (duchas.ie) discussion will be made on death omens in Ireland surrounding three of the main well-known omens – The Banshee, The Death Coach, and The Fetch. But are these omens strictly associated with Irish culture? Are there similar death omens found in other parts of the world? Omens of death have been part of the human experience for centuries, particularly in times before the emergence of scientific thinking, but that’s not to say that signs of demise in beliefs haven’t plagued imaginations in recent years. Omens of death are important aspects of culture, as they often give insight into our own fears surrounding the loss of loved ones and the inability to avoid something we all must face. Death is a universal reality across time and regions, so it is no wonder we have looked for signs of our impending demise.

The Banshee (Bean Sidhe)

Green, in the wizard arms

Of the foam-bearded Atlantic,

An isle of old enchantment,

A melancholy isle,

Enchanted and dreaming lies;

And there, by Shannon's flowing,

In the moonlight, spectre-thin,

The spectre Erin sits.

- From ‘The Banshee’ by John Todhunter, 1888.

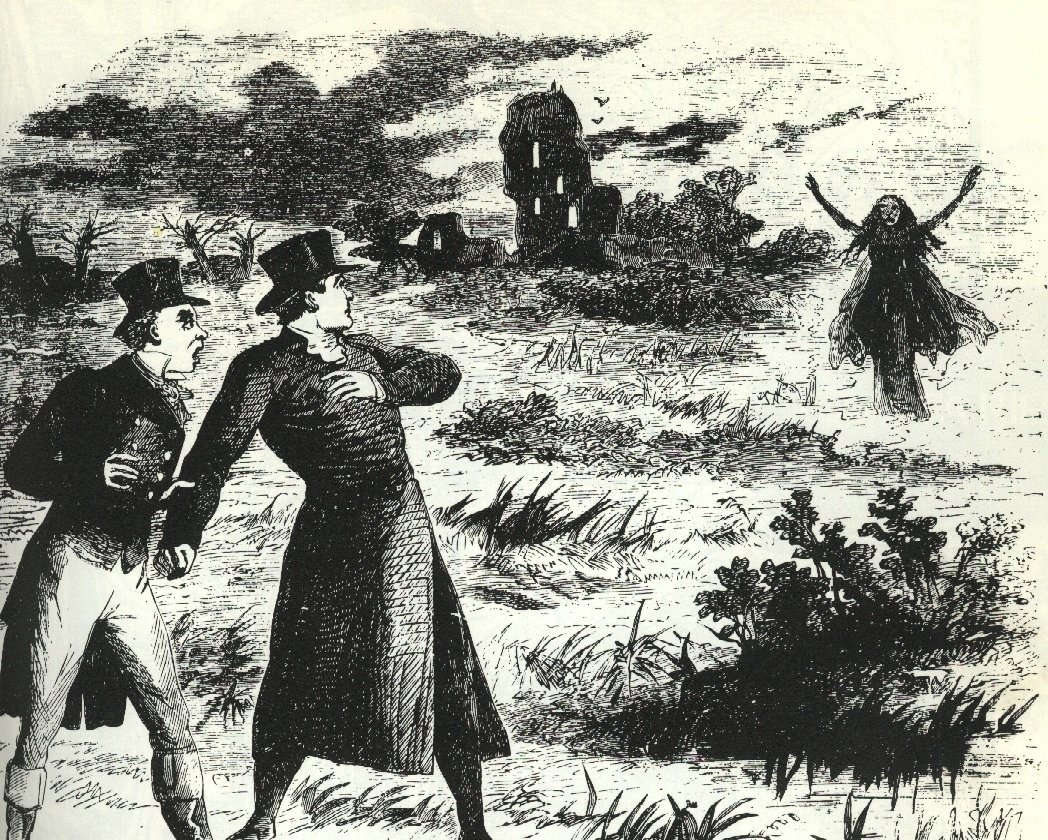

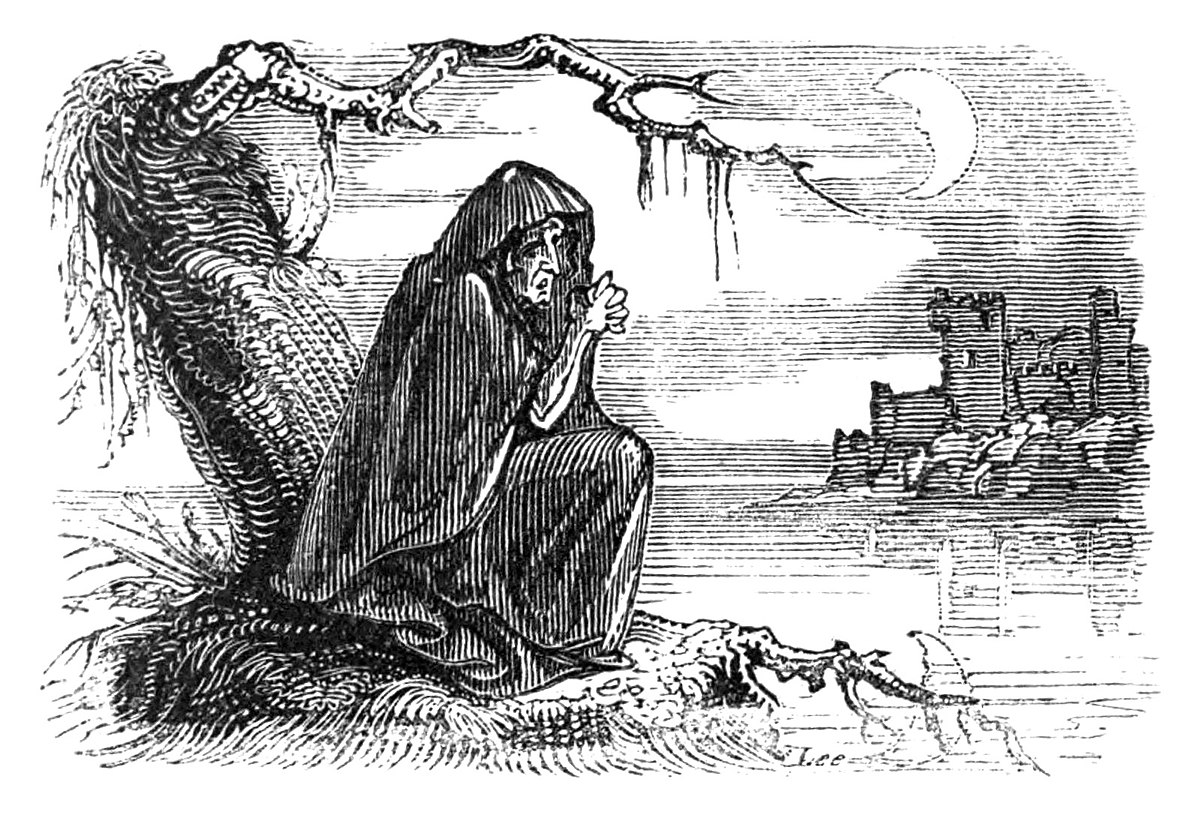

Perhaps the most famous of all Irish legends associated with death is the Banshee or Bean Sidhe, meaning ‘woman of the fairies.’ Most children in Ireland know about this legend, usually told by grandparents or other family members to scare them around Halloween or Samhain. There are endless sources on the Banshee, but all stating she is a supernatural being whose scream foretells the death of the hearer or of one of their loved ones. She usually wears a dark cloak, has a ghostly complexion and has flowing red or white hair. There are conflicting ‘first-hand’ accounts of her age, either stating she is young or siren-like, or old with a hag-like appearance – either a maiden or a crone. It is her cry or scream that terrifies anyone who crosses her path, with Irish families with O’ or Mac/Mc as part of their surname most likely to become a victim to her shrieking. Sometimes she is known as a patron of a clan who paradoxically protects the family by warning of their death. One example in history is the Banshee called Aoibheall who was thought to have forewarned members of the O’Brien family of their deaths at the Battle of Clontarf. The example of Aoibheall also demonstrates that some Banshees were named in history. Other Banshees associated with families included Cliodhana of the MacCarthys and Una of the O’Carrolls.

The Banshee often combs her long hair and will often turn violent or aggressive if someone finds her comb and steals it. Many were often told as a child not to pick up any comb if found near a graveyard as it was likely the Banshee’s. Keening women or bean chaointe (as Gaeilge) were a part of Irish mourning tradition and may have associations with the origins of the Banshee legend. Keening is a physical outpouring of grief, a lament (The Caoineadh) that was formally performed by women in Irish society up until the lament ritual died out in the mid-20th century. The Caoineadh was a formal mourning for the deceased, a ritual carried out in the presence of the corpse and at the graveside. There are some suggestions that the Banshee was a keening woman in life, now taking on the role in death. Some suggest the Banshee is a woman who did not perform the keen properly in life, now a Banshee in death as punishment.

Many writers state she cries for families such as the O’Briens, the O’Connors, the O’Neills, and the O’Gradys to name a few. Sometimes she is described as a washer woman (bean nighe) seen washing the blood-stained clothes of the family member about to die. The idea of a washer woman Banshee associated with death (bean nighe) also has strong links with Scottish folklore. In 1938, an account of the Banshee in Lough Hackett in 1929 was recorded. After a man had drowned in the area many had heard the Banshee crying, and there were reports of her washing her clothes at the spot in which he drowned. An interview collected in the 1970s features an elderly woman in Westmeath who recounts her own encounter with the Banshee. She recounts how she saw the Banshee on a bright night, hearing her wails and seeing her long flaxy hair. The woman talks about how her own mother-in-law was a keening woman and that the Banshee was often thought to be a keening woman herself. Another story from Galway discusses the comb and the Banshee. One night at around midnight, a man came upon the Banshee on his walk home. Startled, she left her comb behind. The man picked the comb up and brought it home with him. Later, he heard screeching outside his window that would not cease until he returned the comb to the Banshee.

A collection of folklore compiled by Irish school children in the 1930s give a sense of the types of stories told by Irish relatives. One boy recounts a story told by his grandfather about the Banshee who appeared at a railway bridge and was associated with the Cooney family. One of the family members – called Pierce - was leaving for America. After two members of the Cooney family passed by his then 15-year-old grandfather at the bridge as Pierce was leaving for the States, his grandfather reported that he, ‘started to hear a woman crying and clapping her hands in a small grove about a hundred yards away.’ He recounted that the sobbing voice said, ‘Don’t go’ and ‘you will be drowned.’ Three weeks later the family were told that Pierce had fallen overboard and drowned, his body was never recovered in the foggy weather. Other members of the same community had also reported that they heard the cries of the Banshee before a Cooney family member died.

The Banshee is also associated with other signs of death in Irish folklore, this includes the sound of three knocks at the door or the sighting of a candlelight in the dark. An example of an account of a knock as a signifier of death comes from Donegal from a woman called Mrs Gallagher who recounted that her grandmother had heard a knock two nights before her grandfather died. One account of death superstitions from Galway details that, ‘if you had a candle in your bedroom at night no fairy would come near you.’ In the 19th century, there were reports that knocks at the door as a death omen was also found in Scotland. The idea of a knock at the door suggests that death itself is looking for admission for the soul – perhaps in the form of the Banshee?

The Banshee Appears by R. Prowse (1862): https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Banshee_Appears_(1862).jpg

The Coiste Bodhar (Death Coach or Coach-a-bower)

We have other omens beside the Banshee and the Dullahan and the Coach-a-Bower. I know one family where death is announced by the cracking of a whip. Some families are attended by phantoms of ravens or other birds.

- From ‘Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry’ by WB Yeats, 1888.

The death coach in Irish folklore is often thought to be summoned by the wails of the Banshee. Some have suggested that the Irish wake traditions persisted to avoid the death coach by drawing the curtains and covering mirrors in the house where a deceased person had been laid out. In Dublin, graverobbers were thought to really push the story of the death coach as a way to keep people inside on dark nights, allowing them to roam the empty streets without trouble. A headless horseman drives the death coach, sometimes thought to carry a black coffin, and is pulled by headless horses (somewhat similar to the Legend of Sleepy Hollow). The headless horseman is thought to make an appearance in folklore tales as far back as the Middle Ages. Like the Banshee, the coach foretells the death of a loved one, and will only leave once it has claimed a soul, but there are instances of people hearing the coach as it travels to claim the person who is marked for death. Also, similarly to the Banshee, some suggest that the horseman who drives the death coach is a fairy of some sort. The creature known as the Dullahan drives the coach (sometimes called Gan Ceann as Gaeilge which means ‘without a head’), a headless male figure that is often said to carry their own rotting head with a hideous grin. Some suggest that the Dullahan is actually the male form of a Banshee. WB Yeats mentions the coach in his collection of Irish Folk Tales. Yeats states the coach will rumble to your door and, if you open it, blood will be thrown into your face. Yeats also states that as well as the coach and the Banshee, some families know death is near by the crack of a whip from the Dullahan or the attendance of ravens. The mention of ravens and death omens is also significant, as ravens have a long association with death and cemeteries in European folklore. Ravens are carrion eaters and of high intelligence, making them the subject of suspicion. In some areas in the southeast of Ireland, the Banshee was also thought to be both the harbinger of death and also associated with battle. Often, she was combined with the warrior goddess the Morrigan, who often took the form of a raven or crow.

The crack of the whip and the sound of the hooves could be heard in the case of the coach, but the Dullahan doesn’t always necessarily show themselves to the hearer. A report from Co Limerick over 100 years ago recounted a tale of two individuals looking up the road in a rural area around 11pm. The writer stated that they heard horse hoofs coming up the road with the noise of the carriage passing them without anything there. They said of the incident, ‘It was a very curious thing indeed and I’ve often thought about it since, but I could never find any meaning for it.’ Often it is stated that the coach travels so quickly it sets fire to the road, and that locks on houses and gates would not deter the coachman - the only thing to scare away the Dullahan was the sight of gold. Another account from a woman called Mrs Sullivan in Limerick in 1936 talks about the speed of the coach. She stated that her parents saw the coach and that, ‘it travelled like lightning and went around the same way three time’ on the main street.

The Death Coach driven by the Dullahan from the film, Darby O Gill and the Little People: https://longforgottenhauntedmansion.blogspot.com/2010/07/death-coach.html

Another entry from the school collection takes about the ‘Headless Coach’ which, ‘used to be called the Coiste Bodhar by the old people.’ The account of the Coiste Bodhar goes on to discuss how the coach was thought to be circular or more like a carriage and drawn by headless black horses. It was reported that a man called William had told the writer that he had seen the headless coachman and the coach about 65 years prior. William’s brother Denis had recently come back from Australia and was dying in his house near him. A few days before Denis died, William reported seeing men on the coach the night his sister-in-law fetched him as she feared her husband would not survive the night.

The most famous headless horseman is found in the tale, ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ by Washington Irving, 1820. The headless horseman in Irving’s tale features a Hessian mercenary who was beheaded by a cannonball. The horseman in death, like the Dullahan, brings death upon the community of Sleepy Hollow. It has been suggested that Irving was inspired by the headless horseman stories of Europe when he wrote the tale.

The Fetch

Entering the lonely house with my wife

I saw him for the first time

Peering furtively from behind a bush --

Blackness that moved,

A shape amid the shadows,

A momentary glimpse of gleaming eyes

Revealed in the ragged moon.

- From ‘Doppelganger’ by James A. Lindon, 1973.

In Ireland, a Fetch is a supernatural double of a living person – like that of a doppelganger. Sighting of a Fetch, particularly at night, is often thought to signify the death of that person. Percy Shelley is thought to have told his wife Mary about meeting his own Doppelganger not long before his own tragic drowning. The ‘Double’ or ‘Wraith’ has been reported in both Ireland and Britain throughout the centuries, and they are often reported as being seen mostly at night time (but they could appear in the day also). Some suggest the word ‘Fetch’ originates from the Irish word for seer or prophet (fáith) - other than that there is very little said about the origins of the term (it may also have some association with Norway and the old Norse language).

It is thought the term dates back as far as the 16th century but rose to prominence in the 19th century when mentioned in the gothic story ‘The Fetches’ by John and Michael Banim. The Fetch was also mentioned in the letters of Sir Walter Scott on Demonology and Witchcraft, 1830. Clodagh Tait discusses the ‘Fetch’ or ‘Wraith’ and reports that some who saw the ‘Double’ did not always die afterwards. Tait also states that often the ‘Fetch’ was considered to be a silent entity, unlike a ghost which would speak or make noise, very much in contrast to the screams of the Banshee.

A depiction of a Fetch from 1891: https://www.libraryireland.com/LegendaryFictionsIrishCelts/Contents.php

The school’s collection shows numerous accounts of Fetches and Wraiths. One entry from Monaghan states that, ‘If you meet a person’s Wraith on the road it is a sure sign he will die soon.’ Another entry from Co Leitrim recounts the story of a woman called Mrs Masterson. The account states that the Brady sisters saw Mrs Masterson driving cows about a mile from her house. As they walked down the road, they looked to Mrs Masterson’s house as they passed and saw her there, saying that she could not have possibly returned in the time it took to walk from the field. She died three days later. The sister’s conclusion was that ‘it was her ‘Fetch’ or ‘Wraith’ that was seen at the house.’ Another account from Donegal discusses the case of a woman called Sarah. It was stated that they thought another woman was staying in the house with her. After a woman actually staying with Sarah left, two men reported seeing another woman enter the house. The woman staying with her went back to check but it was only Sarah there. The story said of the case that, ‘people said that this was Sarah’s wraith or ghost.’

There seems to be some similarities between a ‘Fetch’ and a ‘Changeling’. In Irish folklore, a ‘Changeling’ is a fairy creature who has replaced a human baby that has been stolen by fairy folk. Like a ‘Fetch’, a ‘Changeling’ is a sort of double associated with death too. In pre-famine Ireland, a sickly baby or adult were sometimes considered to be this fairy creature that has been left behind in the place of the abducted. An unbaptised child was thought to be the most vulnerable to abduction, with many parents attributing weakness and illness to the fairy folk. The high rates of child mortality rates at the time and the lack of modern medicine no doubt contributed to the fairy abduction narrative. Fairy doctors were often consulted to help the ‘real child’ come back from the fairy world – herbs such as foxglove (digitalis) were used which no doubt caused harm to the afflicted. Many died because of fairy abduction remedies or simply due to conditions such as tuberculosis or some type of wasting disease. Again, we see a fairy creature– like in the case of the Banshee – associated with death and the time leading up to death.

The word ‘Doppelganger’ has German origins, translated sometimes as ‘double walker’ or ‘double goer.’ Like Irish superstitions, German folklore also suggests that seeing your Double or Doppelganger indicates your imminent death or perhaps of great misfortune. Like the knocks at the door in Irish folklore as a death omen, there were also reports in the 19th century that knocking was also a death omen in Germany, suggesting some links between Irish and German stories. Interestingly, there is also a psychiatric term for someone who sees their double – heautoscopy (HAS). The person experiencing HAS sees a double of themselves in the space around them. Some studies suggest experiencing such phenomena indicates a legion present in the brain. Whether or not that is the case in the examples of ‘Doppelganger’ sightings is hard to tell, considering the widespread sightings of such apparitions and the prevalence of them in folkloric tales.

Ireland and Foreseeing Death

It’s clear that Irish folklore is filled with tales of death and signs that suggest death is near. Although this is not just in Irish culture, with death omens found across the world, death does play a huge part in Irish stories and legends.

Omens of death in Ireland were widespread, with some omens more prominent in society than others. The Banshee, the Fetch and the Death Coach are three iconic tales that still linger in Irish heritage, as so often happens when these kinds of intangible tales are passed on from grandparent to grandchild. Perhaps the reason these omens are still being discussed is because the anxieties surrounding death are still as prevalent as ever. Or perhaps we still like to scare each other on a dark night.

May you be in heaven a full half-hour before the devil knows you’re dead.

- Irish Funeral Toast.

Bunworth Banshee, Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland by Thomas Crofton Croker, 1825: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Banshee.jpg

Sources

Bergen, F.D., Beauchamp, W.M. and Newell, W.W., 1889. Current Superstitions. I. Omens of Death. The Journal of American Folklore, 2(4), pp.12-22.

Blanke, O. and Mohr, C., 2005. Out-of-body experience, heautoscopy, and autoscopic hallucination of neurological origin: Implications for neurocognitive mechanisms of corporeal awareness and self-consciousness. Brain research reviews, 50(1), pp.184-199.

Cassidy, M. 2020. Beyond the Tape: The Life and Many Deaths of a State Pathologist. Hachette Books Ireland.

Harris, M., 2017. Daoine Sidhe: Celtic Superstitions of Death Within Irish Fairy Tales Featuring the Dullahan and Banshee.

Houlihan, M. 2022. Irish Fairies: A Short History of the Sidhe. Tipperary, Ireland.

Lysaght, P., 1974. Irish Banshee Traditions: A Preliminary Survey. Béaloideas, pp.94-119.

Nolan, B. 2020. The Anthology of Irish Folk Tales. The History Press.

Sayers, W. (2017) A Hiberno-Norse Etymology for English Fetch: “Apparition of a Living Person”, ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, 30:4, 205-209, DOI: 10.1080/0895769X.2017.1336073

Sutton-Butler, A. (2023) She is Death: Women as omens of death in paranormal and mythical Ireland. American Paranormal Magazine (October International Edition 2023), pp. 16-19.

Sutton, A. (2021) The Banshee: The female death omen in Irish heritage, The Feminine Macabre Journal (Volume II), Spook Eats Publishing (USA).

Tait, C. (2023) Spectres Across the Atlantic, c. 1820-1940: Communicating with the Dead Over Space and Time. Cultural and Social History, pp.1-18.

Authored by Aoife Sutton-Butler

https://pathologicalbodiesproject.home.blog/