Dogsygen: Celebrating The Secret Lives Of Dogs By Richard Sugg

My new book, Dogsygen, celebrates the Secret Lives of Dogs in a number of different ways. ('Dogsygen' is dogs + oxygen: the whole daily ecology of dog fun, sociability and delight in nature which dogs offer us all across the world.) It showcases some more or less forgotten dogs, once justly famous, such as Bamse of the Norwegian navy, William Butler's sled dog Cerf Vola, Colonel Rawlinson's devoted rescue dog, George, and the strange little dog Stickeen, who shared the greatest adventure on a glacier with the Father of Ecology, John Muir. It recovers the old-school wandering dogs who travelled as freely as cats, in country and city - and in the process made dog friends, or rescued adults, children, and dogs and cats. It also brings back into the light some unjustly neglected dog-lovers: the flamboyant Victorian novelist Ouida, the epically popular working-class prizefighter Tom Sayers, and the celebrity illusionist and friend of Houdini, the Great Lafayette.

It probes into the secret depths of love and devotion which made some dogs give their lives to save children; prompted them to bring food to dogs in distress; saw them wait months or years for a dead owner; pay their last respects at funerals; or simply die of grief when bereaved of their special human. It also reveals levels of intelligence, strategy, reasoning or calculation which all too often have been vaguely degraded to the level of 'instinct'. It recovers the astonishing pride and sense of duty in working dogs, such as Bamse or Just Nuisance, who night after night rounded up drunken sailors and soberly shepherded them into bed.

And Dogsygen leads us into uncanny animal territory in various intriguing ways. We take a glance at dogs who walked back home many miles, using some inexplicable cosmic compass. We meet similar abilities in dogs which somehow always caught the right trains or buses, from Bamse and Just Nuisance through to Railway Jack and Owney, the American postal dog. Certain of these routine homing animals also seemed to know the exact time to be home for breakfast or supper. In the realm of the outrightly ghostly, we join a dog which reacts to a procession of phantom monks seconds before Mrs Joseph Conrad sees them; a Newfoundland which haunts both Dublin cathedral and the grave of his dead master; a dying dog which comes to say goodbye to the little girl she loves in her dream; and the ghost dog of famous breeder and author Albert Payson Terhune, seen by two different friends and one of Terhune's living dogs.

For many people, dogs which actually talk veer between the uncanny or the downright preposterous. Yet a surprising number have made large sums of money, or been vouched for by sceptical journalists, scientists and vets. With the eerie canine calls of 'Hungry', 'I want one', 'I'm clever' and 'Hello my mum' echoing in our ears from Britain to Germany, Italy to America, we also shake paws with non-vocal dogs who display startling levels of intelligence. The Airedale terrier Rolf of Mannheim does sums and holds numerous rational dialogues by rapping his paw for numbers or letters, giving his opinions on World War One and displaying a cheeky sense of humour when bored. Presently his daughter Lola takes up Rolf's knack for arithmetic and conversation, as well as somehow telling the time without the use of a clock.

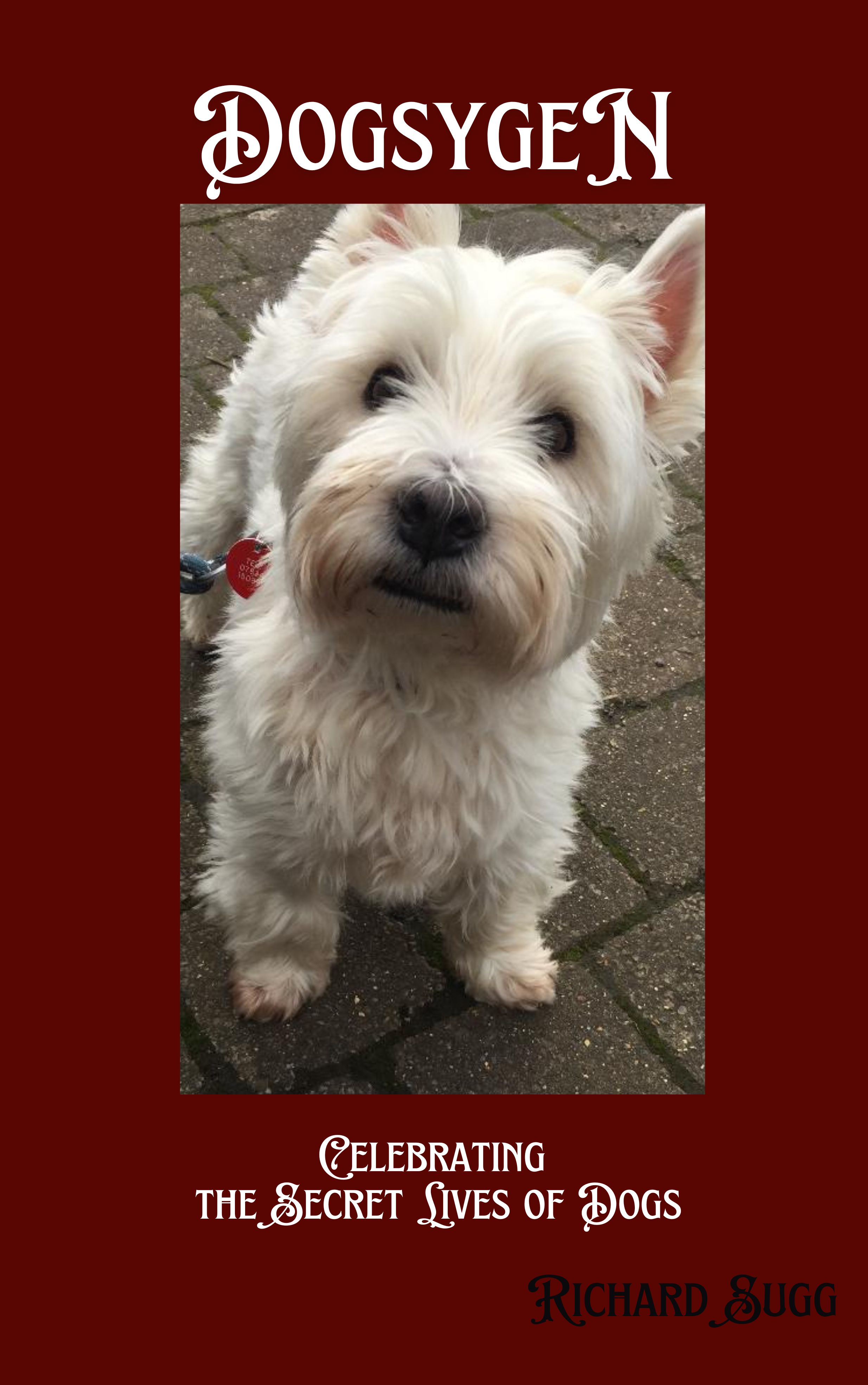

If you want just one animal book to make you laugh and cry, and blink with wonder, this might well be it. I include below a true ghost story in which the dog, Bers, may be alive or dead when she makes her last farewell to a little girl - but which is both uncanny and astonishing in its hints of love and attachment. Our cover star is my friend George of Llandaff, who also gave me an uncanny surprise a few weeks ago, apparently eavesdropping on a conversation about dogs.

- Bers Passes the Baton.

'Sir — in case you are not tired of dog-ghost stories, I can add a small and strange experience that befell us in India. We had two dogs, one a retriever called "Bers", and a pug called "Judy." Judy was a much newer pet than Bers, who had carried my little girl on her back often, and for almost three years had been the faithful slave of this little maid, good-naturedly allowing many liberties, and never resenting or showing boredom, it being harnessed or ridden upon, or rolled over and sat upon. Bers was, in fact, a faithful friend.

But poor Bers caught a chill, and her master took her to sleep in his dressing-room, before the fire, hoping to cure her. One night my little daughter woke at about midnight, and told me she had been "talking to Bers," and that Bers had said to her, "I can't play with you now, anymore, but Judy will play with you now, and be your friend." The next morning we heard that poor Bers had died quietly in the night; dragging herself to her master's side, she expired about midnight.

We have always thought this such a strange thing, for we had not let the child know that her favourite, Bers, was very ill, and even after her death we hid the fact from her for years, saying we had sent her away to get well. Yours, M.G. Crichton'.

Sydney Daily Telegraph, 6 Sept 1904.