Mysteries of Warwickshire Witchcraft

Warwickshire, a picturesque county in the heart of England, is renowned for its charming landscapes, historic towns, and associations with notable figures from the world of magic and witchcraft. From the birthplace of the infamous occultist Aleister Crowley to the founding grounds of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn by William Wynn Westcott, Warwickshire has long been a hub for stories of magic and the supernatural. As we delve into the enigmatic world of witchcraft and explore the mysteries surrounding this area uncovered are cases that attracted the attention of Scotland Yard and occult luminaries like Margaret Murray and Gerald Gardner.

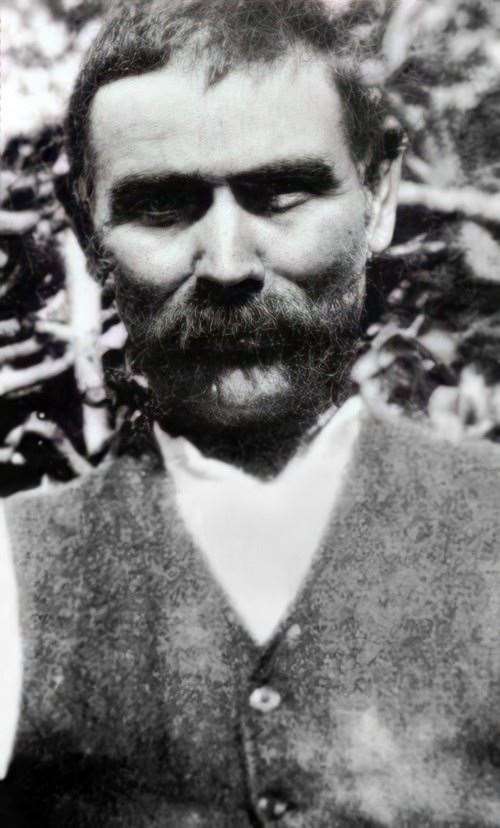

On a chilling St. Valentine's Day in 1945, the quaint village of Lower Quinton in Warwickshire, England, was gripped by a murder mystery that would baffle investigators for generations. Charles Walton, an unassuming 74-year-old farmer and lifelong resident of the village, met a gruesome end on that fateful day. His body was later discovered twisted on the idyllic slope of Meon Hill. Walton’s throat had been slashed deeply by his own trouncing hook and his body pinned to the floor by a protruding pitchfork, and a cross carved into his chest. His murder would become one of the most perplexing cold cases in the annals of the Warwickshire Constabulary.

The murder of Walton was the moment “witchcraft made it into the daily newspapers”, according to the BBC’s now out-of-print 1971 documentary, The Power of the Witch. The investigation was also the final case for retiring chief inspector Robert Fabian, an ageing celebrity detective of the era who bought into the hype that he was the reincarnation of Sherlock Holmes.

The Murder of Charles Walton: The Unsuspecting Victim

Charles Walton was a man of routine, known for his solitary nature and humble existence. A man who was quiet and solitary, known for his reclusive nature and his preference for a life of seclusion in the countryside. He lived in a small cottage at 15 Lower Quinton with his 33 year old niece, Edith Isabel Walton, whom he had adopted and cared for since she was three years old after the death of her mother. His day-to-day life revolved around casual farm work, particularly for Alfred John Potter, the manager of The Firs farm. Walton provided Edith with a modest weekly allowance, covering their housekeeping expenses, rent, coal, and meat. In addition to his occasional farm work, Walton received a meagre old-age pension of 10 shillings a week.

In the 1920s, folklorist and historian J. Harvey Bloom was told of how, in 1885, a young lad from Lower Quinton named Charles Walton ‘met a dog nine times on successive evenings…on the ninth encounter a headless lady rustled past him in a silk dress, and on the next day he heard of his sister’s death’. The incident seems to have left Walton widely mistrusted and even feared in the area, attitudes no doubt exacerbated by his solitary demeanour and the time he devoted to playing with toads, a traditional pastime of witches in the popular imagination.

On the evening of 14th February 1945, the eve of St. Valentine's Day, a gruesome murder took place on the slopes of Meon Hill, near the village of Lower Quinton in Warwickshire, England. The victim of this heinous crime was Charles Walton.

Walton's routine was that of a typical rural worker. He walked with a stick due to his rheumatic joints, but he sought casual farm work wherever he could find it. For the past nine months leading up to his murder, he had been working for Alfred Potter, the manager of The Firs farm, where Walton had been slashing hedges on that fateful day.

On the morning of the murder, Walton left home equipped with a pitchfork and a slash hook, both tools commonly used in farm labour. Strangely, he left his purse behind on this particular day, a detail that would later arouse suspicion. He was last seen passing through the churchyard between 9 am and 9:30 am. His usual routine was to work continuously until around 4 pm, and Edith expected him to be home by that time. However, when she returned home around 6 pm, there was no sign of her uncle.

Concerned for his well-being, Edith sought the help of her neighbour, Harry Beasley, an agricultural worker. Together, they went to The Firs to alert Alfred Potter, Walton's employer. Potter claimed to have seen Charles earlier in the day, working in Hillground, a nearby field. The three of them set out to search for Walton and eventually discovered his lifeless body near a hedgerow.

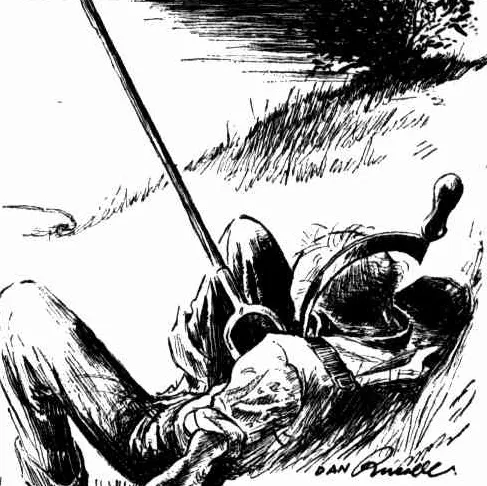

The scene they encountered was nothing short of horrifying. Charles Walton had been brutally murdered. His assailant had beaten him over the head with his own walking stick, slashed his neck open with the slash hook, and driven the prongs of the pitchfork into the sides of his neck, effectively pinning him to the ground. The pitchfork's handle had been wedged under a hedge cross member, and the slash hook had been buried in Walton's neck.

Edith was overcome with grief and shock, and she began to scream loudly. Beasley tried to console her and keep her away from the crime scene. At that moment, another man, Harry Peachey, happened to be walking nearby. Potter called out to him, drew his attention to the gruesome sight, and instructed him to go and notify the police.

Alfred Potter stood guard over the murder scene until the police arrived. The first officer on the scene was PC Michael James Lomasney, who arrived at 7:05 pm. Members of the Stratford-upon-Avon CID arrived later that evening, and at 11:30 pm, Professor James M. Webster from the West Midlands Forensic Laboratory arrived to examine the body. The body was eventually removed at 1:30 am.

The Investigation Unfolds

As the investigation into Charles Walton's murder began, suspicions naturally fell upon Alfred Potter, the man who had last seen him alive and who was his employer. Detective Inspector Tombs took a statement from Potter on 14th February, the day of the murder. Potter had been at The Firs farm for about five years and had known Walton for the duration of his employment there. He stated that Walton had worked for him casually for the last nine months, primarily on hedge-cutting duty. Potter knew Walton's routine well, noting that he typically stopped for lunch around 11 am and worked until approximately 4 pm. He described Walton as an "inoffensive type of man but one who would speak his mind if necessary."

Potter had an alibi for the day of the murder. He stated that he had been at the College Arms with Joseph Stanley, a local farmer, until noon. Afterward, he had gone directly to a field adjacent to Hillground, where he had spotted Walton working some distance away. He noticed that Walton had about 6-10 yards of hedge left to cut when he last saw him, which would have taken about half an hour to complete. Potter believed that Walton would have finished his work and headed home as per his usual routine.

The decision to involve the Metropolitan Police, commonly known as "Scotland Yard," was made early in the investigation. The Deputy Chief Constable of Warwickshire sent a message on 15th February, the day after the murder, requesting assistance:

"The Chief Constable has asked me to get the assistance of Scotland Yard to assist in a brutal case of murder that took place yesterday. The deceased is a man named CHARLES WALTON, age 75, and he was killed with an instrument known as a slash hook. The murder was either committed by a madman or one of the Italian prisoners who were in a camp nearby. The assistance of an Italian interpreter would be necessary, I think. Dr. Webster states the deceased was killed between 1 and 2 pm yesterday. A metal watch is missing from the body. It is being circulated."

The missing pocket watch described in the message added to the intrigue of the case. The watch was identified as a gents plain white metal pocket watch with a snap case at the back, featuring a white enamel face inscribed with "Edgar Jones, Stratford on Avon." It had a second hand and English numerals, valued at 30 shillings.

The initial suspicions that an Italian prisoner of war might have committed the murder were due to the presence of a nearby internment camp housing Italian POWs. However, this theory did not hold up as the investigation progressed.

Detective Inspector Tombs continued to interview potential witnesses and gather statements. More than 500 residents of Lower Quinton and the surrounding area were interviewed, including employees of Potter's farm and anyone who had been in the vicinity on the day of the murder. The local police, assisted by mine detectors from the Royal Engineers, conducted an exhaustive search of the area in the hopes of finding Walton's missing pocket watch or any other significant clues.

As the investigation deepened, Detective Inspector Tombs and his team realised the need for additional expertise. They requested the assistance of Scotland Yard, drawing the attention of Chief Inspector Robert Fabian and Detective Sergeant Albert Webb. Detective Sergeant Saunders, fluent in Italian, was also dispatched to Long Marston to interview Italian prisoners of war.

The Post-Mortem Examination

The post-mortem examination of Charles Walton's body was conducted by Professor James M. Webster on 15th February 1945. The examination revealed gruesome details about the injuries sustained by the victim.

- **Tracheal Incision:** The most significant injury was the incision of the trachea (windpipe) from the back. This injury was consistent with a brutal cut to the throat, which ultimately resulted in Walton's death.

- **Chest Bruises and Broken Ribs:** Walton's chest exhibited severe bruising, and several ribs were broken. These injuries were indicative of significant force applied to the chest area, likely from a physical struggle.

- **Defensive Wounds:** Walton's hands and forearms displayed defensive wounds, suggesting that he had attempted to defend himself against his attacker. These wounds were consistent with a struggle involving two different weapons.

- **Head Injuries:** There were indications of head injuries consistent with a beating. Walton's own walking stick was found near the crime scene, with blood and hair adhering to it, serving as a possible weapon used in the assault.

Based on the examination, Professor Webster estimated that Charles Walton had died between 1 pm and 2 pm on 14th February 1945. The brutal nature of the injuries indicated a violent and frenzied attack.

Alfred Potter's Account

Alfred Potter, who had been the last person to see Charles Walton alive, faced intense scrutiny as a potential suspect in the murder. Detective Inspector Tombs and PC Lomasney, who personally knew the Potter family, observed Potter closely for any suspicious behaviour.

Potter's account of the events on the day of the murder was as follows:

- **Time of Sighting:** Potter stated that he had been at the College Arms pub until around noon. He then proceeded to a field adjoining Hillground, where he saw Charles Walton working in the distance.

- **Appearance:** Potter noted that Walton was dressed differently on that day than usual, wearing only his shirtsleeves instead of his customary overcoat.

- **Return Home:** Potter claimed to have returned home around 12:40 pm. His wife corroborated this timing.

While Potter was initially cooperative with the police, certain details about his actions raised suspicion. He had neglected to mention initially that he had touched the handle of the slash hook and possibly the pitchfork when he first discovered the body. This revelation unsettled his wife, who feared that his fingerprints on the murder weapons would implicate him.

Throughout the investigation, Potter maintained that the murder was the work of an Italian prisoner from the nearby camp, fueled by news of an Italian detainee being arrested. His focus on this theory seemed to grow stronger as the days passed.

Gerald Gardner's Perspective

During the investigation into Charles Walton's murder, the case attracted the attention of Gerald Gardner, a prominent figure in the modern witchcraft movement. Gardner's interest in witchcraft, folklore, and the occult led him to comment on the case in his book "The Meaning of Witchcraft," published in 1959.

Gardner acknowledged the murder and the attention it had received but did not delve deeply into the details of the case. Instead, he used it as a reference to discuss the broader topic of witchcraft, its history, and its relationship with the modern witchcraft revival.

In his book, Gardner explored various aspects of witchcraft, including its historical roots, rituals, and beliefs. He also addressed the misconceptions and stereotypes surrounding witches and their practices. While he acknowledged the existence of witch trials and persecution throughout history, he argued that modern witchcraft was a revival of ancient pagan traditions rather than a continuation of malevolent witchcraft.

Margaret Murray, another influential figure in the study of witchcraft, would also contribute her opinion on the Charles Walton murder, adding an academic perspective to the case.

Margaret Murray's Involvement

Margaret Alice Murray, a prominent Egyptologist and anthropologist, was well-known for her controversial theories on witchcraft and the witch trials. Her work on the witch-cult hypothesis, which proposed that witchcraft was the survival of an ancient pagan fertility religion, had a significant impact on the study of witchcraft in the early 20th century.

In the context of the Charles Walton murder, Murray was drawn into the investigation due to the public's fascination with the occult and the possibility of an occult ritual connection to the crime. Her expertise in witchcraft and folklore made her a sought-after authority on the subject.

Murray's involvement in the case likely centred around providing an expert opinion on whether there were any occult or ritualistic elements involved in the murder. Her perspective would have been valuable in either confirming or dispelling the notion that witchcraft played a role in the crime.

As the investigation continued, the combination of police work, forensic analysis, and expert opinions would shed light on the circumstances surrounding Charles Walton's murder. While the murder weapon, the pitchfork, seemed to add an eerie dimension to the case, investigators would ultimately seek to uncover the motive behind this brutal and perplexing crime.

The Pitchfork as a Murder Weapon

One aspect of the Charles Walton murder that generated significant attention and speculation was the use of a pitchfork as the murder weapon. The pitchfork's association with rural labour and its seemingly ritualistic appearance fueled rumours of witchcraft involvement in the crime. Some believed that the choice of weapon and the manner of the attack were indicative of occult practices.

However, it's essential to address the practicality of using a pitchfork in a rural setting. In farming communities like Lower Quinton, pitchforks were commonplace tools used for various agricultural tasks, including haymaking, straw handling, and clearing debris. The presence of a pitchfork at the scene of the murder might not have been as sinister as some believed, given Walton's occupation as a farm labourer.

It's also worth noting that the pitchfork had pragmatic utility as a weapon. Its long handle allowed for reach, and the prongs could inflict puncture wounds that might be perceived as ritualistic but could have also been the result of a frenzied attack.

James Hayward's Influence

To understand the broader context of witchcraft beliefs in the area, we must delve into the story of another individual from Warwickshire: James Hayward. His beliefs and actions would play a role in connecting the murder of Charles Walton to the idea of witches in the community.

James Hayward, a farm labourer, was known for his fervent conviction in the existence of witches in the vicinity of Lower Quinton. His beliefs were not merely superstitious; they bordered on obsession. Hayward firmly believed that witches were responsible for his misfortunes, particularly his poor work performance and perceived bewitchment.

In an effort to confirm his suspicions, Hayward sought the guidance of a local Cunning Man and Water Doctor known as Manning, whose real identity was traced to Robert Manning of Alcester. Manning instructed Hayward in a peculiar method of identifying bewitchment: inspecting his urine. According to Manning's instructions, if bubbles rose to the top of a bottle or phial filled with Hayward's urine, it indicated that he was under a spell.

This belief in bewitchment and Hayward's determination to break the alleged curse led to a tragic incident that would be mistakenly linked to the murder of Charles Walton. Hayward's case demonstrates the extent to which belief in witchcraft persisted in the region. Using the inquest report and an article from the Stratford Advertiser reporting upon the murder, the facts of the case of poor Ann Tennant show how much water the bewitching charge, discredited as the ravings of a madman, actually holds. Here we may discover the origin and source of many of the stories associating this part of Warwickshire with witchcraft.

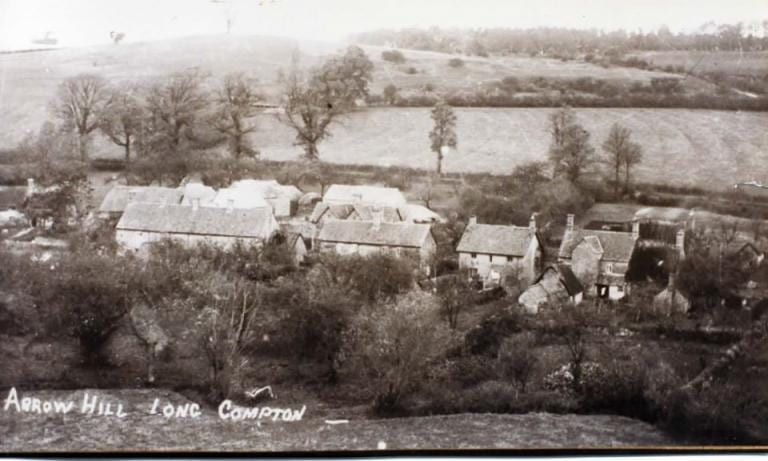

The Quiet Village of Long Compton: The Brutal Attack

On Wednesday 15th September 1875, a farm labourer returning home from a day's work viciously attacked an elderly lady. The attack left Ann Tennant bloody and dying, while the assailant was arrested for her murder. James Hayward showed no remorse for attacking Ann Tennant, insisting that she was the leader of a coven of fifteen other witches in the area, all of whom he could name and would deal the same treatment if he would be allowed. Moreover, he expressed his lack of concern that she could die from her wounds.

On the fateful day in 1875, James Hayward had been working with others in a harvest field and was returning home at around eight o'clock in the evening. Sadly, Ann Tennant was also on the turnpike road after fetching a loaf of bread, and upon seeing the elderly lady, Hayward struck Tennant several times with a two-pronged fork, inflicting fatal wounds upon the 79-year-old.

When the police constable arrived and arrested Hayward at the scene, the inquest reports that the assailant remarked:

"There are fifteen more of them in the village that I will serve the same. I will kill them all."

Hayward blamed his poor work in the harvest field that day on Ann Tennant, who he claimed had possessed him and, at the sight of her, he stabbed her in the legs with his fork before witnesses restrained him. The comparison with the murder of Charles Walton, and the idea of a ritual method for disposing of a witch, is here diminished by the testimonies of the many witnesses at the Coroner's Inquest, held at the Red Lion Inn the following Friday.

A Closer Look at the Murder

There is no mention of a bill-hook (a hedge laying tool) or the slashing of Tennant as Hayward was concerned with nothing other than drawing blood upon the old woman. It appears that Hayward lost control of his wits and was thrown into a violent rage after the first blow landed. One is inclined to believe that it was not the original intent, however fleeting that may have been, to murder poor Tennant. There is irrefutable evidence to the effect that he had declared no regret should the old lady die during his arrest, even suggesting that there were more women he might kill if opportunity afforded him the chance. However, these seem to be the ravings of a man in the grip of a fury, his wits having left him entirely. It is clear from later remarks to the Police Superintendent that he hadn't meant to "kill her outright," but rather he was acting spontaneously. Hayward's erratic behaviour and irrational accusations made it clear that he was suffering from delusions related to witchcraft.

Hayward's attack on Ann Tennant, while horrific, differed significantly from the murder of Charles Walton. His method of assault involved multiple puncture wounds to Tennant's legs, seemingly intended to draw blood but not to kill her outright. This act, driven by irrational beliefs, demonstrated the extent to which superstition and mental instability could influence an individual's actions.

The subsequent legal proceedings revealed Hayward's fragile mental state, leading to his confinement in Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, where he spent the remainder of his life. His case is a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked superstition and irrational beliefs, as well as the potential for tragic consequences.

The Belief in Bewitchment

Hayward's obsession with witchcraft is revealed in the inquest through several of his comments regarding witches. James Thompson, Police Superintendent, remarked that Hayward "...wanted to show me some witches that were in the jug of water... He said it was only those that had witches about them that could see them." The jury at the Coroner's Inquest recorded a verdict of "wilful murder," and the killer was to stand trial at Warwick Assizes. The witness statements confirmed that Hayward was excited and frenzied during the attack, while the victim's husband and daughter both confirmed a long acquaintance of some 30 years with the murderer, reflecting upon his persistent delusions about witchcraft.

James Hayward was not alone in his belief in bewitchment at the time, although he did display an unusual conviction in his behaviour towards what could be regarded as folk superstition. His fervent beliefs were frequently remarked upon in statements at the Coroner's Inquest, and such was Hayward's conviction that bewitchment was to blame for his misfortune that he had previously sought out that folk figure who is renowned for opposing witchcraft: the Cunning Man.

The local Cunning Man and Water Doctor, known enigmatically as Manning, apparently gave Hayward a method for identifying bewitchment by inspecting his urine. Once the cause was apparent, it has been speculated that the Cunning Man informed Hayward of the best way to rid himself of the problem. More accurately, the method of getting the better of the witch and removing their power is to draw blood on them. The story goes that Manning told Hayward to "turn upside down a bottle or phial filled with his urine. If bubbles came to the top, it would mean that he was, indeed, under a spell."

The Folklore of Warwickshire

The folklore of Warwickshire makes a number of enigmatic references to Long Compton witchery, including the story of a young man marking a circle and reciting the Lord's Prayer backward to summon the Devil. Just a decade before the murder of Ann Tennant, there was another victim attacked for bewitchment in nearby Stratford upon Avon, toward the south of the county. John Davies believed that the only sure way to rid himself of bewitchment was to draw the blood of the witch and was charged with assaulting Jane Ward after causing a gash in her cheek. So, the killer of Anne Tennant was not an isolated account of such a belief in the area. Charles Godfrey Leland in his "Etruscan Roman Remains" cites a similar belief among Venetians, that a witch loses their power if wounded and their blood spilt.

The Legend of Long Compton

The murder of Ann Tennant, James Hayward's obsession with witches, and the broader belief in witchcraft in Warwickshire contributed to the development of a local legend centred on Long Compton. The legend perpetuated the idea that the region was a hotbed of witchcraft and occult practices.

According to some versions of the legend, James Hayward was attributed with a statement that there were enough witches in Long Compton to pull a cart up nearby Meon Hill. This assertion, while made by an individual suffering from delusions, added to the mystique surrounding the area.

Belief in witches and superstitions surrounding them was not uncommon in the past, and stories like those of Hayward and Tennant reflect the lingering folk beliefs of the time. The legends and tales that have emerged from these events provide insights into the enduring fascination with the supernatural, but they should not overshadow the reality of these historical cases. Through these stories, we gain a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between magic, superstition, and the human experience in this enchanting corner of England.