The Breath of Life: Exploring the Origins, Physiology, and Mysteries of the Soul

The concept of the soul is as ancient as humanity itself, tracing its roots to the dawn of civilization. Across cultures and epochs, the soul has been interpreted through many lenses, but common threads have emerged, linking the soul to breath, life force, and spiritual essence. From the Sanskrit "atman" to the Latin "fumus" and the Greek "psyche," linguistic connections reveal that many words for the soul derive from terms related to air, breath, or smoke. This linguistic evidence offers us a glimpse into how ancient peoples understood the soul—primarily as something ethereal and invisible, yet crucial to life.

The physiology of the soul and its relationship with the body has perplexed philosophers, theologians, and medical scholars for millennia. Where exactly does the soul reside? Is it located in the brain, the heart, or another organ? How does it enter the body, and where does it go after death? Through an examination of ancient texts, cultural traditions, and scientific inquiry, we will explore how different civilizations conceptualised the soul, the body, and the relationship between them.

The word "soul" in various languages often traces back to the idea of breath or air. In Sanskrit, "atman" refers to the inner self or soul, derived from a root word meaning "breath." This association with breath as the essence of life is mirrored in many ancient languages and cultures.

In Latin, "fumus" means "smoke," another word that suggests something transient and intangible, rising into the air much like breath leaving the body. In Greek, the word "psyche" also means both "soul" and "breath," while "thymos" and "pneuma" represent concepts of spirit or life force tied to the act of breathing. The Hebrew term "ruach" similarly means "breath" or "spirit," while the Arabic "nafasun" refers to breath as the animating force within a person.

In Old Slavic, the term "dhuma" carries the meaning of "smoke" or "breath," further cementing the connection between the soul and the ethereal. Across these ancient linguistic landscapes, we find a common theme: the soul is intimately tied to the most basic act of life—breathing. Without breath, there is no life, and without the soul, there is no essence.

In ancient times, understanding the relationship between the soul and the body was a complex and often spiritual undertaking. Early civilizations believed that the soul resided in specific organs, with various theories emerging in different cultures. The ancient Egyptians, for instance, believed the heart was the seat of the soul, and during mummification, they preserved the heart while removing other organs, signifying its vital connection to the afterlife.

Greek philosophers also wrestled with the concept of the soul's location within the body. Aristotle viewed the soul as the form of the body, essential to its function, while Plato saw the soul as distinct from the body, residing temporarily in the physical form. For Plato, the soul was immortal, pre-existing before birth and continuing after death. He located different aspects of the soul in various parts of the body—the rational soul in the brain, the spirited soul in the chest, and the appetitive soul in the stomach or liver. This tripartite model deeply influenced Western thought for centuries.

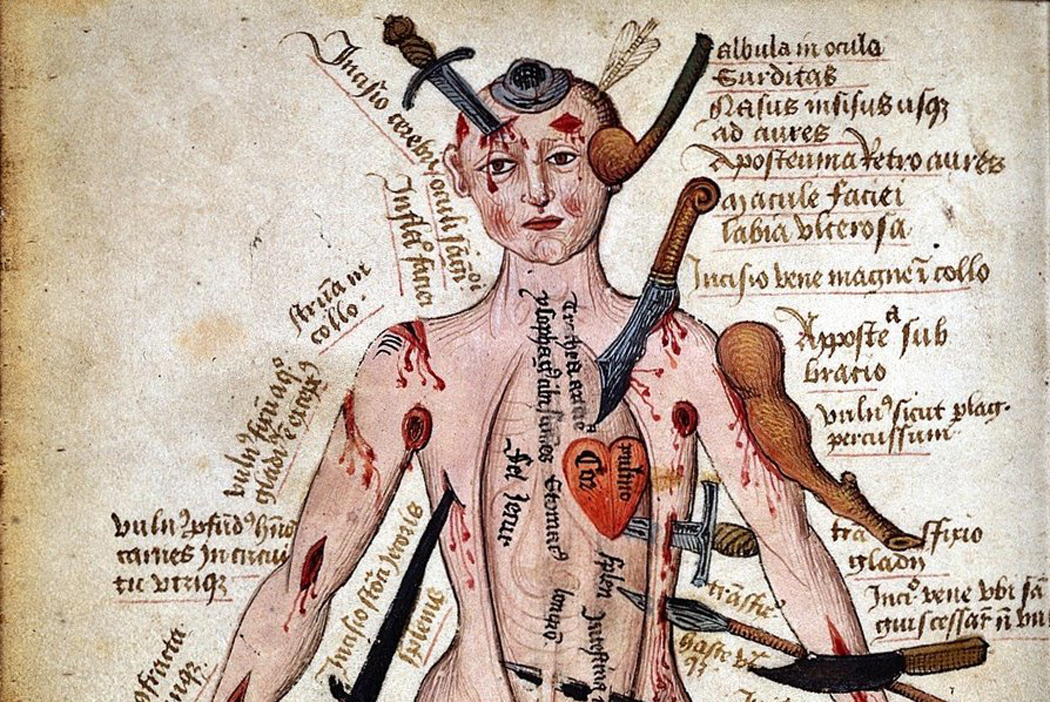

In Rome, Galen, a physician and philosopher, contributed to the idea that the soul was connected to the body's vital functions. He linked the soul to the bodily humours—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile—which were believed to control a person's temperament. For example, a sanguine temperament was associated with an abundance of blood, while melancholy was linked to an excess of black bile. The balance or imbalance of these humours was thought to affect not only physical health but also the state of the soul.

The belief in the four humours dominated medieval and Renaissance medicine and philosophy. The humours were not only considered bodily fluids but also as connected to one's personality, emotions, and soul. Sanguine (blood), choleric (yellow bile), melancholic (black bile), and phlegmatic (phlegm) temperaments were tied to the balance of these fluids, and this balance was seen as a reflection of the health of both body and soul.

Thomas Walkington, an English theologian and philosopher, once wrote: "In the elements consists the body, in the body the blood, in the blood the spirits, in the spirits the soul." This encapsulates the belief that the soul is both separate from and intrinsically linked to the physical body. The soul’s health was reflected in the body’s physical state, and an imbalance in the humours could signal a troubled soul.

Walkington’s assertion was not unique. The idea that the soul was a kind of subtle vapour or spiritual substance within the blood was shared by many early scholars. This concept also extended to religious practices, where blood sacrifices were seen as a way to communicate with the gods or the afterlife. Blood, being a vehicle of life, was also thought to carry the soul.

One of the greatest mysteries surrounding the soul has been the question of its entry and exit from the body. In many traditions, the soul was believed to enter the foetus at a specific point in development. Aristotle suggested that the soul entered male foetuses at 40 days and female foetuses at 90 days, a belief that was later adapted by various Christian theologians. The idea of "quickening," when a pregnant woman first feels the foetus move, was also seen as evidence of the soul’s arrival.

As for the soul's departure at death, different cultures developed elaborate rituals to ensure a smooth transition to the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians believed that the soul would be judged by Osiris, with the heart weighed against a feather to determine its purity. In Greek mythology, souls crossed the River Styx to reach the underworld. In Christianity, the soul’s destination—Heaven or Hell—depended on one’s faith and deeds in life.

The question of the soul’s location in the body was often debated, with many scholars suggesting that the brain might be its primary seat. This theory was championed by thinkers like René Descartes, who believed that the pineal gland in the brain acted as the point of connection between the soul and the body. However, others, like Vesalius, one of the fathers of modern anatomy, were unable to find conclusive evidence of a specific “organ of the soul” during dissections, leaving the question unresolved.

In medieval Europe, questioning the nature of the soul could lead to accusations of heresy. The soul was considered the most vital aspect of human existence, and to dispute its nature was to challenge religious doctrine itself. The case of Michael Servetus, a Spanish physician and theologian, is an example of how dangerous these debates could be. Servetus questioned the doctrine of the Trinity and proposed radical ideas about the nature of the soul. For his views, he was burned at the stake in 1553.

The idea that the soul could die with the body was also considered heretical. Such beliefs were seen as a denial of the Christian promise of eternal life. Nevertheless, these ideas persisted, often underground, influencing later developments in philosophy, literature, and science. The soul became a point of contention, not just in religious circles, but in the emerging world of scientific inquiry.

By the time of the Renaissance, the debate over the soul had become a crisis of thought in Christian Europe. Anatomical dissections revealed nothing of the soul, and yet religious faith demanded belief in its existence. Figures like Andreas Vesalius and John Milton grappled with this paradox. Vesalius, though a pioneer in anatomy, never found evidence of a soul during his dissections, yet he remained a believer. Milton, in his epic poem Paradise Lost, portrayed the soul as the eternal essence of humanity, tied to both divine grace and human frailty.

The invention of the novel and modern drama allowed for new explorations of the soul's nature. Characters in plays and novels became vessels for exploring inner life, morality, and the eternal struggle between body and spirit. Witchcraft, heresy, and the search for the soul's true nature were all part of this cultural landscape, reflecting society's deeper anxieties about the afterlife, identity, and the nature of existence.

From ancient beliefs linking the soul to breath and smoke, to modern debates over its existence, the soul has remained a profound and elusive concept. While we may never fully understand the soul’s nature or its exact location within the body, its enduring presence in religious, philosophical, and scientific thought testifies to humanity’s eternal quest for meaning. The soul, like breath itself, is both invisible and essential—a reminder of life’s fragility and the mysteries that lie beyond.

You can discover more via the following podcast with guest Dr Richard Sugg:

Link to The Smoke Of The Soul by Dr Richard Sugg: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Smoke-Soul-Science-Religion-Invention-ebook/dp/B08HDJNWV8