The Haunting of Christmas Nights

In the long, dark winter months of old Britain, the heart of the home was the hearth, where families gathered for warmth and comfort. Yet, it wasn’t just the glow of the fire that pulled them close. It was the stories—the ghostly tales spun from lips quivering not just with cold but with the thrill of dread. For centuries, these were the tales that marked Christmas, a time when the line between the living and the dead seemed thinner, when ancient spirits brushed against the world of the living.

In those times, Christmas was not the twinkling holiday we know today. It was a solemn, mystical season, tied to the natural world and the cycles of death and rebirth. Yule, the ancient pagan festival, marked the longest nights of the year when the spirits of the dead were thought to wander. As the year grew old, the earth seemed to die with it, and the veil between the worlds became porous. These were times of cold, darkness, and introspection. And what better way to confront these forces than by telling tales of those who had crossed over, of spirits who lingered?

Robert Burton, in the 17th century, remarked on the enduring custom of telling 'merry tales' at Christmas, but these were no light-hearted stories. They were of witches, fairies, and goblins—creatures that roamed the night, unseen but felt, ready to seize a careless soul. The stories may have been 'merry' in the sense that they were shared over good company and good cheer, but their subjects were anything but.

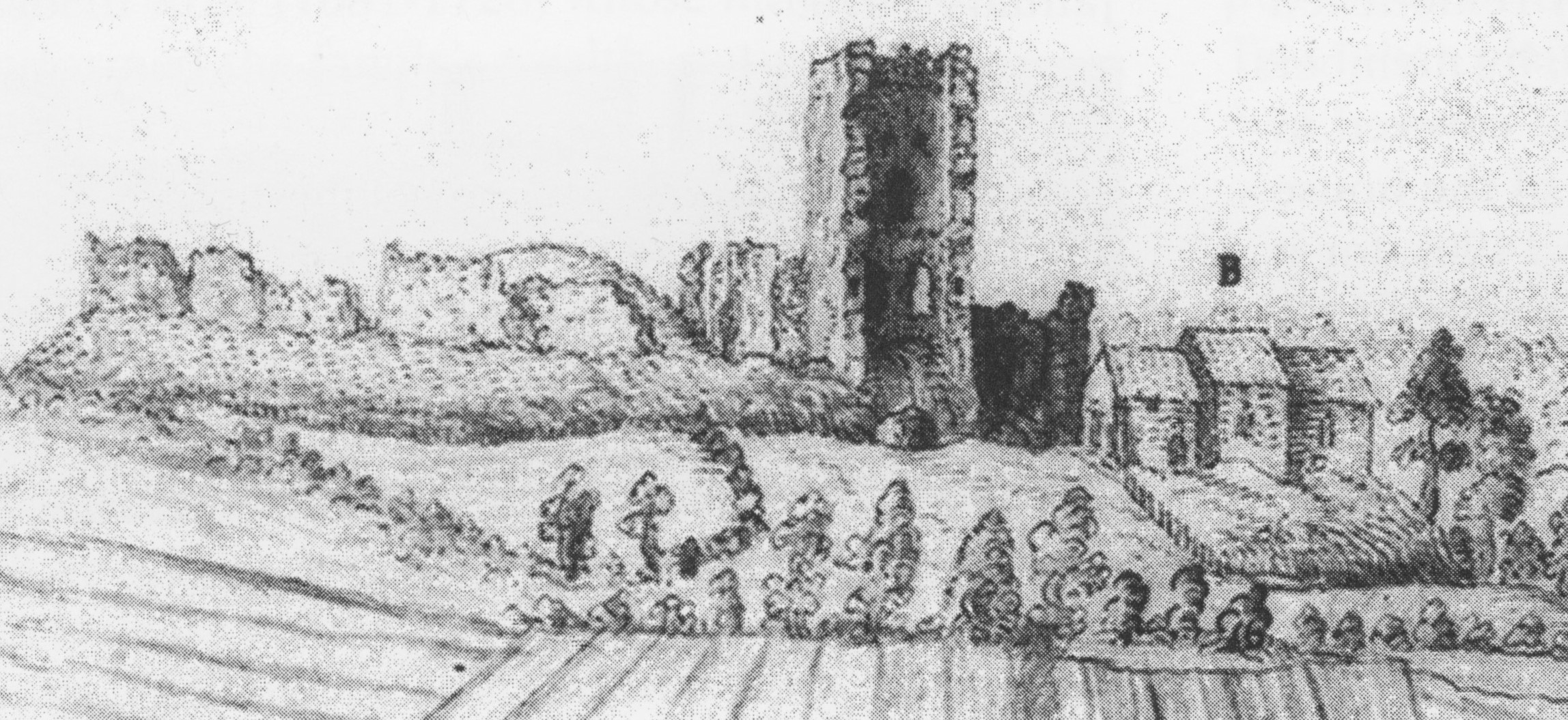

In the shadow of such a tradition is the tale of Bramber Castle, a ruin now, but once the seat of the powerful de Braose family. In the early 13th century, William de Braose, the fourth lord of Bramber, made the fatal error of crossing King John. His lands were seized, his family pursued relentlessly by the king’s forces. Of all the tragedies that could befall a noble house, perhaps none is darker than the fate of William’s children.

Legends persist that the de Braose children were taken by the king and starved to death in the cold, stone walls of Windsor Castle. It is said their cries for food echoed through the castle’s corridors, unanswered, until silence finally claimed them. But that silence did not last long.

In Bramber, far from Windsor, on the quiet, mist-shrouded roads that wind through the village, the ghosts of these children are said to roam. Ragged, gaunt, and pale, they are seen by those unfortunate enough to pass by after dark. They chase travellers, begging for food, their bony hands reaching out, their faces hollow with hunger that no meal could ever satisfy.

During the Christmas season, when the chill in the air cuts sharper and the nights stretch long, the children return to Bramber Castle itself. They stand, a boy and a girl, watching over the crumbling ruins of their former home. Their eyes are hollow, their gazes empty, but there is something mournful in their vigil. Villagers whisper that they are waiting—for what, no one knows. But each year, the stories come back, and with them the same sense of dread. Perhaps it is not the cold that raises the hairs on the back of the neck, but the knowledge that something old and hungry still lingers in the village.

Across the country, in the wilds of Scotland, another haunting tale unfolds. Penkaert Castle, nestled in the rugged landscape of Lothian, stands as a testament to centuries of history. Its stones have weathered wars, sieges, and the brutal winds of winter, but its darkest story comes not from battle, but from a single cold night in the 17th century.

On that night, a beggar named Alexander Hamilton, worn and haggard from his travels, knocked on the heavy wooden door of the castle. He asked for food, for shelter from the biting wind. But the laird’s family, their hearts as cold as the winter air, turned him away. They wanted no part of his misery, no part of his curse, for that was what he left them with as he trudged back into the night. Alexander Hamilton, they said, spat on the threshold and muttered dark words under his breath—a curse on the family that had refused him.

Days later, the lady of the house and her young daughter fell ill. It was a sickness like no other, swift and cruel, and no healer in the land could cure it. They withered away, their bodies racked with fever, until death finally took them. In the village below, whispers began. They said it was the beggar’s curse, that he had returned from the grave to claim his revenge.

The laird, desperate to rid his house of the evil, had Hamilton tried as a witch. The trial was no more than a formality, and Hamilton was swiftly executed. His body was burned, his ashes scattered. But even in death, the beggar found no peace. His spirit lingered in Penkaert Castle, forever tied to the injustice done to him.

In the years that followed, strange things began to happen in the old laird’s mansion. The halls, once filled with the sound of laughter and music, now echoed with footsteps that belonged to no living soul. Doors creaked open on their own, shadows flitted at the edge of sight, and in the dead of night, a low, mournful wail could be heard.

But it was on Christmas night in 1923 that the most chilling event took place. The laird’s descendants had gathered in the castle’s grand music room, the air filled with the warmth of a fire and the sound of carols. As they sang, the carved wooden family crest that hung above the fireplace began to move. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, it leaned forward away from the wall. The singing faltered as one by one, the family members noticed it. There was a moment of eerie silence as the crest paused, suspended as if caught between worlds. And then, just as slowly, it returned to its place.

No one spoke of it that night, but the next morning, as they sat around the breakfast table, the conversation inevitably turned to the strange occurrence. Each of them had seen it, each of them had felt the chill that came with it. Some said it was the ghost of Alexander Hamilton, still wandering the halls, still seeking retribution. Others whispered that it was the spirits of the laird’s wife and daughter, forever bound to the place of their untimely deaths.

The castle, they said, had become a place of restless souls, a place where the past refused to stay buried. And so, each Christmas, as the family gathered once more, there was always a sense of unease, a feeling that they were not alone.

These stories, these whispers of the past, are more than just tales to pass the time. They are the echoes of a world where the living and the dead are never far apart, where the cold breath of winter carries with it the sighs of those long gone. At Christmas, when the days are shortest and the nights are longest, when the world holds its breath in anticipation of the new year, it is as though the old spirits take one last chance to make themselves known.

Perhaps it is in the telling of these tales that we honour them, that we remember those who came before, those who suffered, those who were wronged. Or perhaps it is something more. Perhaps in the cold, dark nights of Christmas, we come closest to understanding the thin line that separates the living from the dead, the fleeting nature of life itself.

So, as you gather by the fire this Christmas, remember the old ways. Remember the stories of ghosts and spirits, of curses and hauntings. For in the telling of these tales, we keep the ancient traditions alive, and with them, the spirits of Christmas past.

For more ghostly tales this Christmas you can listen to Owen Staton share some Welsh tales from around the firepit : https://www.podpage.com/haunted-history-chronicles/christmas-ghosts-by-the-firepit-tales-with-owen-staton/