For centuries, the figure of the highwayman has occupied a prominent place in British folklore. These daring outlaws, who preyed upon travellers along the country’s roads, have been both feared and romanticised. Their exploits have been immortalised in ballads, books, ghost stories and later, in the pages of history. While some highwaymen were nothing more than common thieves, others became legendary figures, their names etched into the annals of criminal lore. This post delves into the world of highwaymen and women across the United Kingdom, exploring who they were, what they did, and the punishments they faced. It also tells the tale of one of the unluckiest highwaymen, Horace Wright, whose misguided aspirations led him down a tragic path.

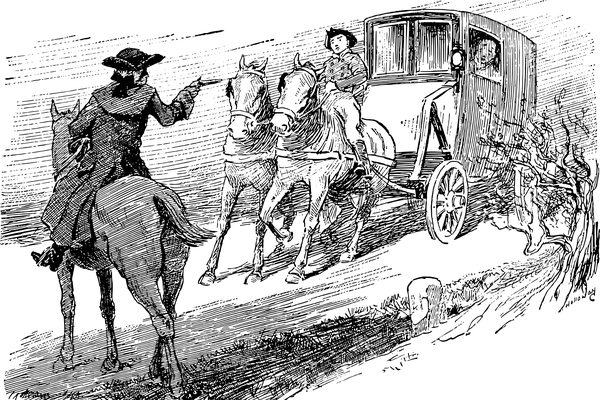

Highwaymen were robbers who plied their trade on the country’s roads during the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries. They typically targeted wealthy travellers, merchants, and stagecoaches, demanding money or valuables under the threat of violence. While most highwaymen were men, there were a few notable women who also took up this dangerous profession.

Highwaymen were often portrayed as dashing, charismatic figures, thanks to the popular literature of the time. Stories of their daring exploits, chivalry, and stylish appearance captured the public’s imagination. Many were depicted as noble robbers who only targeted the rich, sharing a portion of their ill-gotten gains with the poor. However, the reality was often far less glamorous. Highwaymen were criminals, and their actions frequently involved brutal violence.

Highwaymen operated throughout the United Kingdom, from the remote Scottish Highlands to the rolling hills of the English countryside. They were particularly active on the main routes leading into London, where they could ambush wealthy travellers heading to and from the capital. The methods they used varied, but the most common involved lying in wait along secluded stretches of road or in wooded areas.

One of the most famous highwaymen was Dick Turpin, who became a legendary figure in British folklore. Turpin began his criminal career as a member of the Essex Gang, a group of cattle thieves. He later turned to highway robbery, earning a reputation for his audacity and ruthlessness. Turpin’s most famous exploit was his supposed ride from London to York on his horse, Black Bess, in a single night to establish an alibi for a crime. Although this tale is likely a fabrication, it cemented Turpin’s status as a folk hero.

Another well-known highwayman was Jack Sheppard, who gained fame not just for his crimes but for his numerous escapes from prison. Sheppard was a skilled carpenter who turned to theft and robbery. He was captured multiple times but managed to escape from custody on four occasions, earning him the nickname "The Gentlemen's Thief." His exploits were celebrated in popular ballads, and he became a symbol of defiance against authority.

In contrast to these celebrated figures, many highwaymen were ordinary criminals who met with swift and brutal justice. They were often pursued by local constables or soldiers, and when caught, they faced severe punishment.

The British legal system was harsh on highwaymen. Once captured, they were typically tried in the local assizes, where the evidence against them was often overwhelming. The punishment for highway robbery was usually death by hanging, a sentence carried out publicly to serve as a deterrent to others.

Execution was not the only punishment meted out to highwaymen. In some cases, they were sentenced to be "hanged in chains," a particularly gruesome form of post-mortem punishment. Their bodies were left to rot in iron cages suspended from gibbets, often at the site of their crimes, as a warning to others. This practice was known as "gibbeting" and was intended to instil fear in the population.

In other cases, highwaymen were transported to penal colonies in Australia, where they faced a life of hard labour in harsh conditions. This was seen as a more lenient sentence, but for many, it was effectively a death sentence, given the brutal conditions they endured.

The exploits of highwaymen captured the public’s imagination, and their stories were spread through ballads, pamphlets, and later, novels. These stories often exaggerated or romanticised the deeds of these criminals, turning them into folk heroes. The tales of Dick Turpin, Jack Sheppard, and others were retold in countless forms, from broadsheets to penny dreadfuls, contributing to the myth of the noble highwayman.

The romanticization of highwaymen was not without consequence. For some, these tales inspired real-life criminal activity. The idea of living outside the law, thumbing one’s nose at authority, and gaining fame and fortune through daring exploits was appealing, particularly to those who felt marginalised or disenfranchised by society.

One such individual was Horace Wright, a young man whose obsession with the highwaymen of old led him down a path of crime and ruin. Born in the mid-19th century, Horace Wright grew up reading sensationalist literature that glorified the lives of highwaymen like Dick Turpin and Jack Sheppard. These stories captured his imagination, and he became determined to emulate his heroes.

Horace’s first attempt at highway robbery occurred on November 5, 1868, when he hired a horse in London and set out for Oxfordshire. His target was an ironmonger named Frank Strange Copeland, whom he encountered riding a cart with his wife near Henley. Wright, dressed in a costume inspired by the illustrations of 17th-century highwaymen, pointed a loaded pistol at Copeland and demanded money.

However, Copeland’s reaction was not what Horace expected. Instead of handing over his valuables, Copeland asked if Horace was joking. The sight of the young man in his outdated, dandyish outfit likely seemed more ridiculous than threatening. Realising that he had chosen his victim poorly, Horace rode off.

Undeterred by his initial failure, Horace attempted another robbery later that day, this time targeting a man named Richard Cripps Lloyd near the village of Shiplake. Once again, his efforts were thwarted when Lloyd informed him that he had no money. Frustrated, Horace fled the scene.

Horace’s ineptitude as a highwayman did not go unnoticed. He was arrested the next day at the Red Lion Inn, a few miles from Henley. When police searched him, they found a loaded pistol hidden in his jack boots, along with a black mask in his pocket—a clear sign that he had intended to commit further robberies.

During his trial, Horace’s defence was that he had been in a state of great excitement and that his actions were a result of a foolish obsession with the highwaymen of old. He pleaded guilty to the charges but claimed that he had no intention of going through with the robbery. The jury, recognizing his fragile mental state, recommended mercy. The judge sentenced Horace to one month of imprisonment, hoping that the young man would learn his lesson.

Unfortunately, Horace Wright did not learn his lesson. Less than a year after his release, he was arrested again for highway robbery, this time in Cambridgeshire. His method had not improved; he once again attempted to rob travellers but took "no for an answer in a very peaceable, not to say sheepish, manner," according to the Oxford Times.

During his trial at the Cambridgeshire assizes, Horace’s defence attempted to delay proceedings to gather medical testimony regarding his sanity, but the judge refused. Horace was found guilty and sentenced to nine months of imprisonment with hard labour.

Less than a year after completing his sentence, Horace was in trouble with the law again. This time, he was charged with stealing £30 from his employer, Mr. Samuel Cropper of Cheapside. Rather than making the payment as instructed, Horace used the money to hire a horse and absconded. He was eventually tracked down and arrested at a labourer’s cottage in Cambridgeshire.

During his trial at the Middlesex Assizes, Horace expressed remorse for his actions, but he also admitted that the allure of the highwayman lifestyle had once again overwhelmed him. He was sentenced to 18 months of imprisonment.

After his third imprisonment, Horace Wright’s name disappeared from the headlines. It is unclear what became of him, but it is likely that his repeated brushes with the law and his obsession with highwaymen left him a broken man. His story is a cautionary tale of how the romanticization of crime can lead vulnerable individuals down a dangerous path.

The stories of highwaymen and women across the United Kingdom are filled with adventure, crime, and, often, tragedy. These figures have been both feared and romanticised, their exploits immortalised in folklore and literature. While some, like Dick Turpin and Jack Sheppard, became legends, others, like Horace Wright, serve as reminders of the darker side of these tales.

Highwaymen were not noble outlaws but criminals who preyed on the vulnerable. The harsh punishments they faced reflect the severity with which society viewed their crimes. Yet, the myths surrounding them continue to capture our imagination, a testament to the enduring power of storytelling and the complex relationship between history and legend.

For more tales and ghostly accounts of highwaymen make sure to listen to the podcast episode here: https://www.podpage.com/haunted-history-chronicles/spectral-highwaymen-ghosts-of-the-open-road/