The Art Of Dying

In the midst of the religious and spiritual fervour of the medieval era, a literary and artistic movement emerged that focused on the art of dying, known as the ‘Ars Moriendi’. This Latin term translates to "The Art of Dying," and it encompassed a collection of texts and visual depictions that aimed to guide individuals through the spiritual and psychological challenges of approaching death. These works, composed during the 15th century, offered practical advice and spiritual insights to individuals facing their mortality. ‘Ars Moriendi’ addressed the anxieties surrounding death, offering guidance on how to maintain faith, resist the temptations of the Devil, and ultimately achieve a peaceful passage to the afterlife.

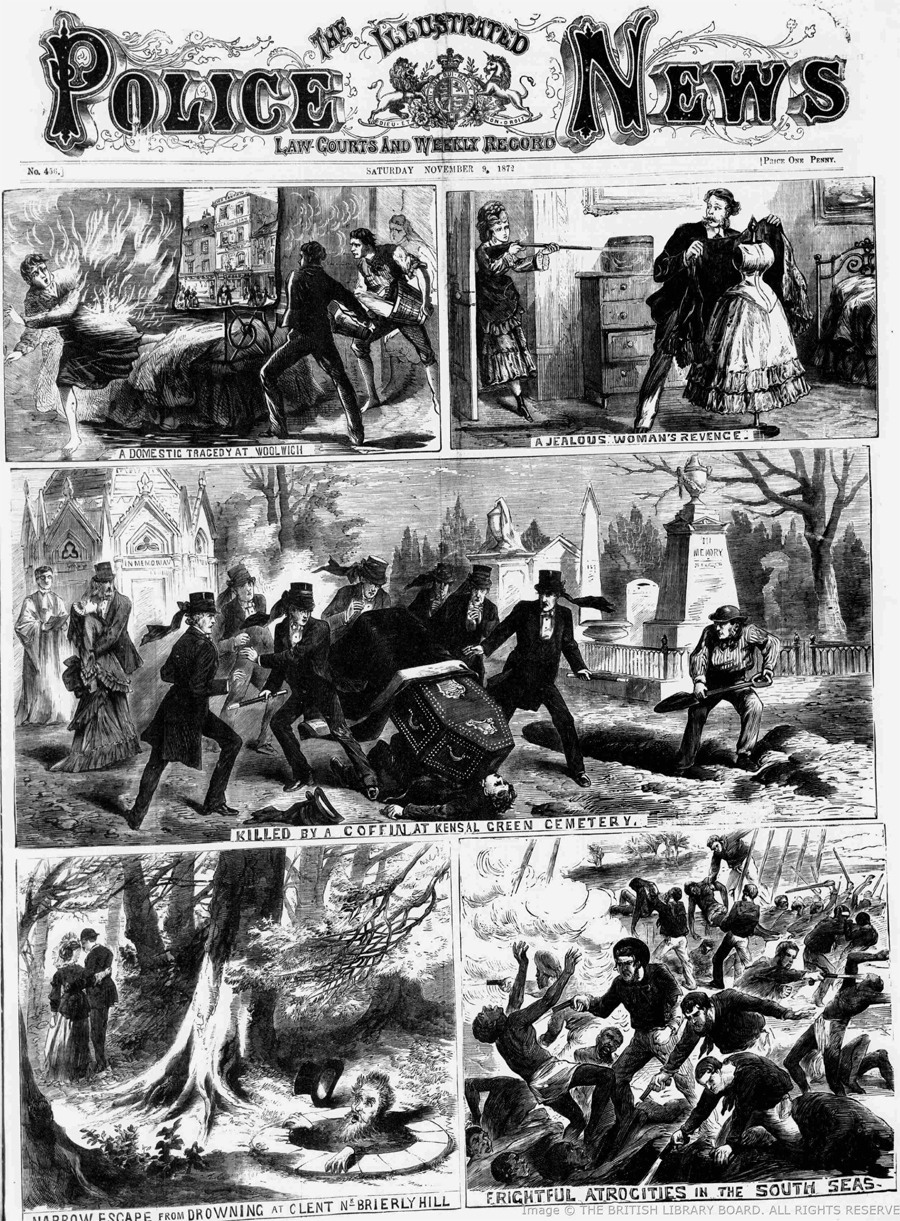

Fast forward to the Victorian era, a period marked by a fascination with death and elaborate mourning rituals. The significance of Victorian burials, mourning, and treatment of the deceased was deeply intertwined with the prevailing beliefs about the afterlife. The ‘Ars Moriendi’ tradition found resonance in Victorian culture, which placed a heavy emphasis on the concept of a "good death." The rituals surrounding death and mourning were believed to have a direct impact on the soul's journey to the beyond. The elaborate funerals, meticulous mourning attire, and even the practice of post-mortem photography were all part of the effort to ensure a peaceful transition of the departed's soul to the next realm.

Victorian Burials and the Passage to Eternity

The Victorian approach to burials and mourning was heavily influenced by the belief that the manner in which a person was laid to rest and the rituals observed could influence their fate in the afterlife. The elaborate funerals, complete with ornate coffins, horse-drawn processions, and grand monuments, reflected the society's desire to show respect and honour to the deceased. These practices were thought to be instrumental in securing a soul's safe passage to eternity.

Mourning rituals and attire were also meticulously observed during the Victorian era. The strict codes of dress, including the wearing of black garments and veils, were not merely symbolic; they were seen as acts of devotion that would aid the departed soul in its journey. The ‘Ars Moriendi’ ideals of maintaining faith, avoiding despair, and embracing a peaceful death found parallels in the Victorian emphasis on maintaining decorum and exhibiting stoic acceptance of loss.

In essence, the significance of Victorian burials and mourning practices was deeply rooted in the belief that proper observance could influence the fate of the departed in the afterlife. Just as the ‘Ars Moriendi’ provided guidance for a virtuous passing, the Victorian culture sought to ensure that the deceased's journey to eternity was one of honour, respect, and spiritual peace. This interconnectedness between belief systems, rituals, and the treatment of the deceased underscores the profound ways in which cultural and spiritual ideals shaped the approach to death during these eras.

The emphasis on a "good death" and the intricate belief systems surrounding the afterlife in the Victorian era gave rise to a booming funeral industry. As society became increasingly invested in ensuring a peaceful transition for the departed, funeral practices evolved into elaborate and meticulously planned events. Funeral directors, embalmers, and mourning outfitters catered to the growing demand for services that aligned with the prevailing spiritual beliefs. This surge in demand not only led to the expansion of existing funeral-related businesses but also spurred the emergence of new enterprises specialising in various aspects of the funeral process. The funeral industry, once a relatively modest trade, became a thriving economic sector, marked by advertisements offering a range of funeral options and mourning paraphernalia. From the grandest funerals attended by large crowds to the more modest burials for the working class, the funeral industry catered to all levels of society, reflecting the pervasive influence of the Victorian culture's intricate beliefs about death, the afterlife, and the journey in between.

Victorian funerals were a thriving industry. Indeed, funerals catered to all echelons of society. At their most extravagant, they had the power to bring even the grand metropolis to a standstill. Upon the passing of the Queen's Consort, Prince Albert, the entire realm entered a period of mourning. Not only did church bells toll across the land, but many churches also conducted special services, and numerous shops in towns remained closed. Following the demise of the Duke of Wellington, a crowd exceeding 65,000 individuals gathered to pay their respects as he lay in state. On the day of the funeral itself, the bells in the Tower Hamlets tolled at minute intervals throughout the day. According to The Times, a staggering ninety percent of shops were entirely shuttered, while the remainder were only partially open.

That the funeral business was an excellent trade can hardly be doubted. One writer in Leisure Hour in 1862 describes the business as extortionate.

“In numberless instances the interment of the dead is in the hands of miscreants, whom it is flattery to compare to the vulture, or the foulest carrion bird… the morality is, in their hands, to use a plain word, robbery.”

The grieving often found themselves coerced into spending more than what was either necessary or prudent, resulting in inflated prices paid for no purpose other than to augment the profits of those within the industry. However, not everyone reaped benefits from the funeral business. When a funeral evolved into a major occasion, it had consequences for tradespeople as well. A linen-draper, writing to The Times on 4 June 1830, observed that upon King George IV falling ill, his flourishing trade in "coloured silks, prints, ribbons, and every kind of fancy and coloured goods" had come to a halt. He lamented that "all my hopes are blighted." Three weeks later, the King passed away, and a 45-day period of general mourning was declared. As this period concluded on 11 August, it was "clearly... influenced by a considerate regard to the damage which the manufacturers... suffered due to the event." Furthermore, upon the death of the Duke of Wellington, letters surfaced in The Times on 24 September 1852, highlighting the economic impact that a period of mourning would have on trade. Similarly, following the passing of Queen Victoria, the Secretary to the Drapers' Chamber of Trade penned a letter to The Times on 26 January 1901. He proposed that the twelve months of Court Mourning would significantly affect the retail drapery trade, which orders its goods three or four months in advance. He further recommended that the Earl Marshall establish a shorter period for public mourning, suggesting a duration of three months.

While grand funerals were, naturally, a rarity, it appears that a funeral was accessible to individuals from all walks of life. This is evident in a mid-century advertisement found in The Times, which presented a selection of six categories of funerals. These ranged in price, starting from 21 pounds for a first-class burial and descending to 3 pounds and five shillings for the sixth class. Even these prices could be reduced further, “by dispensing with the funeral cortege through the streets of London.” Instead, the Necropolis Company suggested that the body be taken by special train from their private station to Woking Cemetery, “to relieve the public from unnecessary and costly display.”

By the middle of the century, funerals had evolved into a significant industry, prompting Mr Punch to offer his commentary. Alluding to the proliferation of advertisements for funeral services, he remarked that there surely must be, “different qualities of grief… according to the price you pay.”

“For £2 10s., the regard is very small. For £5, the sighs are deep and audible. For £7 10s, the woe is profound, only properly controlled; but for £10, the despair bursts through all restraint, and the mourners water the ground, no doubt, with their tears."

Writing in Curiosities of London Life (1853), Charles Manby Smith had few positive words for the industries catering to funerals.

“Here, when you enter his gloomy penetralia, and invoke his services, the sable-clas and cadaverous- featured shopman asks you, in a sepulchral voice- we are not writing romance, but simple fact- whether you are to be suited for inextinguishable sorrow, or for mere passing grief; and if you are at all in doubt upon the subject, he can solve the problem for you, if you lend him your confidence for the occasion… Messrs. Moan and Groan know well enough, that when the heart is burdened with sorrow, considerations of economy are likely to be banished to the memory of the departed; and, therefore, they do not affront the sorrowing patrons with the sublunary details of pounds, shillings, and pence…. For such benefactors to womankind- the dears- of course no reward can be too great; and, therefore, Messrs. Moan and Groan, strong in their modest sense of merit, make no parade of prices. They offer you all that in circumstances of mourning you can possibly want; they scorn to do you the disgrace of imagining that you can drive a bargain on the very brink of the grave; and you are of course obliged to them for the delicacy of their reserve on so commonplace a subject, and you pay their bill in decorous disregard to the amount. It is true, that certain envious rivals have compared them to birds of prey, scenting mortality from afar, and hovering like vultures on the trail of death, in order to profit by his dart; but such “comparisons,” as Mrs Malaprop says, “are odorous,” and we will have nothing to do with them.”

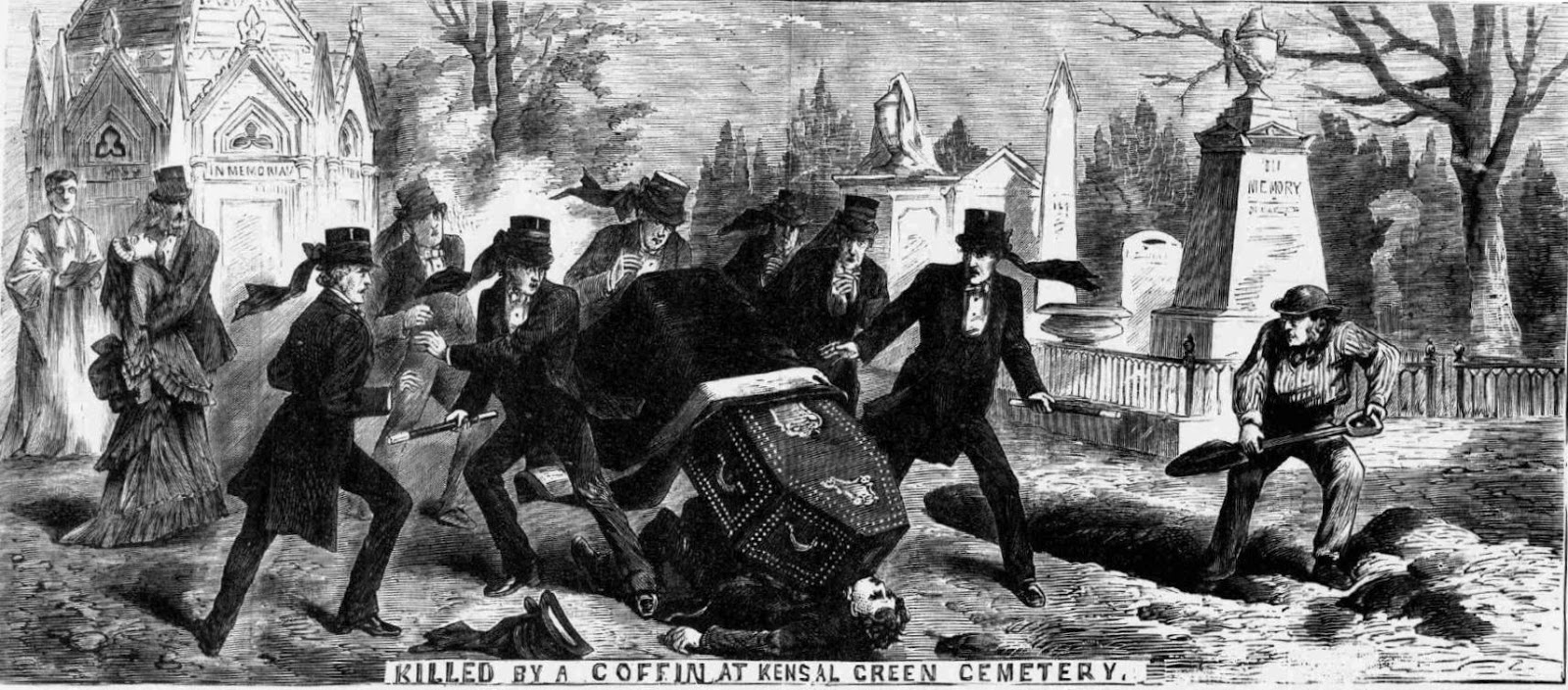

The Victorian era, with its intricate mourning rituals and elaborate funerals, was a time of solemnity and respect for the deceased. However, amidst the carefully orchestrated processions and meticulous preparations, there were instances when burials took an unexpected turn, revealing the complexities and challenges of handling the departed with care and dignity. One such incident that shook the Victorian community occurred on the fateful day of Saturday, 2nd November 1872, when the shocking death of pallbearer Henry Taylor made headlines, shedding light on the perils that could arise during the sombre act of burial.

The Background of the Unfortunate Event

During the 19th century, funerals were often grand affairs, involving multiple pallbearers responsible for carrying the heavy coffin. These individuals played a crucial role in ensuring a dignified farewell for the deceased, bearing the weight of the departed as well as the emotional responsibility of conveying their respect. However, on that fateful November day, the proceedings at this particular funeral took a devastating turn.

The Tragic Sequence of Events

The funeral procession was underway, with mourners paying their respects to the departed as the coffin was solemnly carried to its final resting place. Henry Taylor, one of the pallbearers entrusted with this solemn duty, took his position alongside his colleagues. As the coffin was being lowered into the grave, tragedy struck. An unforeseen mishap occurred, causing the coffin to slip from the grasp of those carrying it, plummeting downward with an unimaginable force.

The Horrific Outcome

The full weight of the coffin, along with the body it held, landed with brutal impact on Henry Taylor's jaw and chest. The crushing force was more than his body could bear, and the consequences were devastating. Henry Taylor's life was tragically cut short in a shocking accident that none could have foreseen. The incident left mourners and onlookers in a state of disbelief, as the sombre occasion turned into a scene of distress and chaos.

The Aftermath and Public Reaction

The news of Henry Taylor's shocking death spread rapidly, capturing the attention of the Victorian community. The incident highlighted the fragility of life even during moments that were meant to be dignified and respectful. It also drew attention to the physical challenges faced by pallbearers in fulfilling their duties, often in difficult and emotionally charged circumstances.

Front-Page Headlines

The tragic death of Henry Taylor made its way to the front pages of newspapers, serving as a stark reminder of the risks involved in the funeral industry. The press coverage brought attention not only to the unfortunate incident but also to the broader issues surrounding the safety and protocols of burials. The incident prompted discussions about how to prevent such accidents and protect both those involved in funerals and the sanctity of the ceremony itself.

Lessons Learned and Ongoing Impact

The death of Henry Taylor served as a turning point in the Victorian funeral industry, prompting a reassessment of safety measures and practices. While it was a tragic event, it led to a greater awareness of the importance of providing pallbearers with proper training and support to prevent similar accidents in the future.

The shocking death of pallbearer Henry Taylor on that fateful November day in 1872 exposed the vulnerabilities that could arise even during the most carefully planned and orchestrated funerals. This incident serves as a reminder of the challenges faced by those responsible for handling the deceased and the need for continuous improvement in safety protocols. As we reflect on this tragic event from the Victorian era, we are reminded of the fragility of life and the significance of ensuring that even in moments of grief and mourning, the utmost care and respect are extended to both the departed and those who carry them to their final resting place.