Victorian Mourning Superstitions and Traditions

“Ring the bell softly,

There’s crape on the door” J.M Hunt

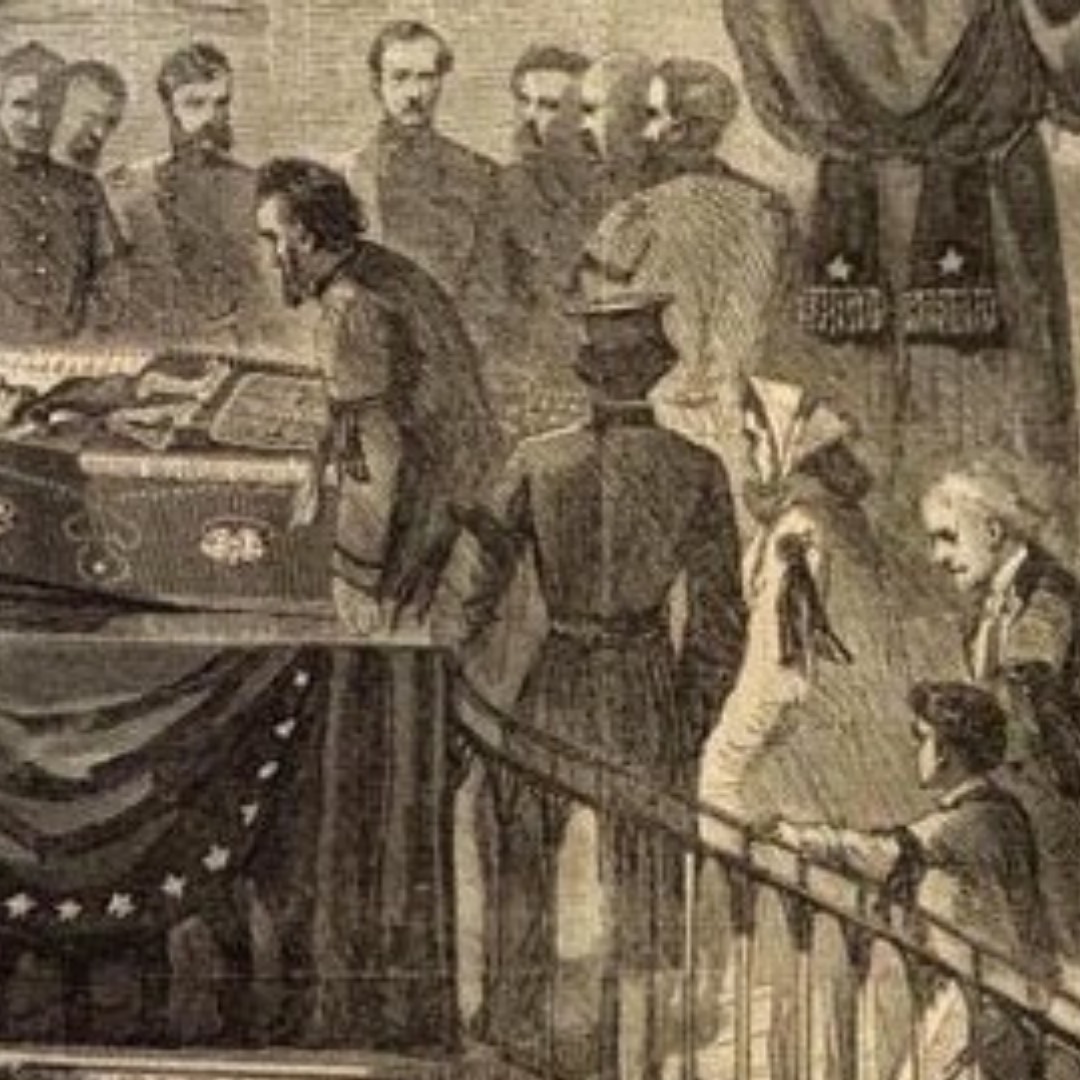

The Victorians are known for their rituals and traditions and our Christmas customs aren’t the only things that we have inherited from this particular period. Our weddings, christenings, and funerals are all marked by this era. For the Victorians, these were events of incredible import, and since the mortality rate, particularly for children, was so high, funeral traditions gained particular importance as the century progressed.

As the 19th century began, Britain began to see the emergence of a financially stable middle class, and with it, came improved life expectancies.

Early deaths were viewed increasingly as tragic and deserving of elaborate and grand-scale mourning. Funeral and mourning practices were further ritualized when Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Consort Alfred, died. She went into deep mourning for the remainder of her life and set a precedent which many of her British subjects followed. Death practices (and related superstitions) became more elaborate as the century progressed; however, toward the end of the 1800s, the ostentatious show had begun to diminish, and by the 1890s, funerary practices were relegated to a prescribed set of social rules.

Even though the life expectancy was improving for the middle and upper classes, death unfortunately was still around every corner for the lower classes. To try and counter high mortality rates these individuals took whatever precautions (effective or not) to protect themselves by ensuring that the deceased’s spirit found its way to the afterlife and did not linger to take anybody else with them. This period of history saw the clash of science and spirituality with the question of what was next in the afterlife debated and investigated by academics and people of note from a variety of professions. It is no surprise to see that with this would come a wealth of folklore and superstitions regarding the deceased and proper mourning.

Bodies were mostly held in the home for days after a death, so the wellbeing of a soul in the lead up to the funeral was of paramount concern and so many practices were incorporated to aid the transition. At the moment of death the family of the deceased would draw the curtains and stop the clocks at the time of death to mark the exact moment the deceased had passed away. In mourning customs, it was commonplace to drape all reflective surfaces with black fabric, but mirrors would receive special treatment and so crepe or veiling would be used to cover the mirrors throughout the house to avoid trapping the spirit of the deceased in the looking glasses. Only after the body had left the house and entered the earth could the mirrors finally be revealed to the household.

Family photographs would be turned face down throughout the house to prevent the deceased person’s spirits from possessing relatives and friends. If several members of the same family passed away then everyone that entered the house would wear a black ribbon to prevent the deaths spreading even further. This practice would even apply to dogs and chickens. The family would hang a wreath of laurel and yew or boxwood, tied with black crepe or ribbons, on the front door as a signal to neighbors and visitors that a death had occurred. The bell knob or door handle would also be draped with black crepe, and tied with a ribbon – black if the deceased were married or aged and white if he or she were young or unmarried. When the time came for burial the body was removed from the house head-first in order to prevent the soul from calling others to follow it.

Further considerations and superstitions would extend all the way through to the burial itself with funerals not being delayed. The longer the delay, the more likely someone else in the family would die. It was considered bad luck to happen upon a funeral procession and if you found yourself in this predicament then etiquette determined you doff your cap or avert your eyes and bow your head to avoid the bad luck. The funeral procession would take alternate routes to and from the churchyard so as to prevent the soul returning home- the feet of the deceased often being tied so as to prevent the soul from wandering also. If by chance the lost soul did manage to return home however they would find their rooms often rearranged. The belief that the movement of fixtures and fittings being something that would cause confusion and result in the spirit leaving again. Funerals would be organised with an even number of mourners so as to prevent the departed soul reaching out to take a companion with them. Rain on the day of the funeral would be considered lucky and a sign that the deceased would make it into heaven- an old rhyme says,

Happy is the bride

That the sun shines on

Happy is the corpse

That the rain rains on.

The rumble of proceeding thunder at a funeral was the sign that the soul had in fact been accepted.

Today mourning rituals still play a similar role. While today’s mourners may not be quite like Victorian traditions, our own traditions continue to help all who have lost loved ones find strength in unity. From funeral attire to funeral songs, these rituals help us find peace.

Sources

The Encyclopedia of Superstitions

By Richard Webster