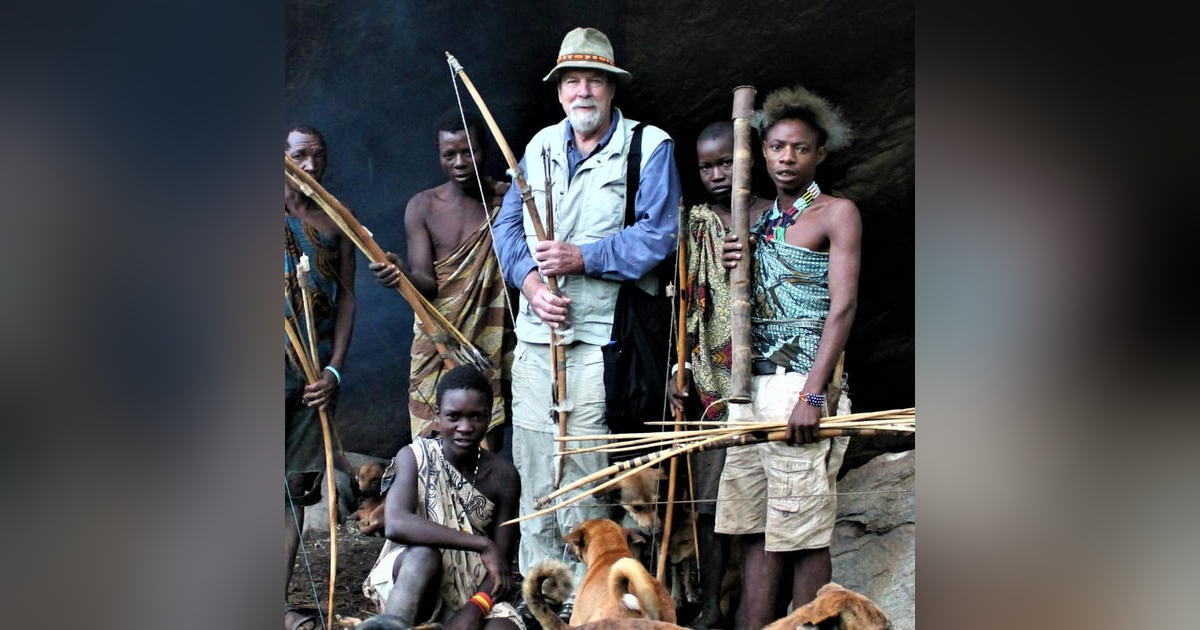

James Dorsey Encounters the Hadza Tribe in Western Tanzania

Guest: James Michael Dorsey

- Award-winning author, explorer, and lecturer

- Has spent over three decades researching remote tribal cultures in over 50 countries

- Resident naturalist for 22 years at a whale sanctuary in Baja, Mexico

Episode Summary:

In this episode, Andrew speaks with James Michael Dorsey, an award-winning author and seasoned explorer. James shares a remarkable travel story from his journey to western Tanzania, where he encountered the Hadza, one of Africa's last true hunter-gatherer tribes. From facing thrilling tests of trust with the tribe to becoming "bait" in a dramatic hunt, James' experiences reveal the deep cultural insights he gained while documenting vanishing cultures. He also discusses his parallel passion for cetacean research, which led him to a whale sanctuary in Mexico. Listen in to discover the adventures and insights that have shaped his career.

Topics Covered:

- Introduction to James Michael Dorsey

- The Hadza Tribe: Last True Hunter-Gatherers in Africa

- Preparing for Remote Expeditions: Permits, Planning, and Survival

- First Encounters and Tests of Trust with the Hadza

- Facing an Angry Baboon: James’ Most Unforgettable Travel Story

- Insights on Cultural Preservation and Storytelling

- Cetacean Research and Whale Encounters in Baja, Mexico

- Reflections on a Life of Adventure and Exploration

Resources and Links:

- James Michael Dorsey’s website: jamesmichaeldorsey.com

- The Lagoon: Encounters with the Whales of San Ignacio by James Michael Dorsey

Call to Action:

- Check out our website at oneofftravelstories.com

- If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe, rate, and review the podcast.

- Share your favorite travel stories with us on social media using #OneOffTravelStories.

00:00 - None

00:23 - Intro

02:01 - Meeting James

07:51 - Story Background

17:46 - James finds the Hadza

22:00 - The Hunt

31:42 - Leaving Tanzania

38:28 - Conclusion

Speaker 1

[00.00.00]

And suddenly everything's very quiet. I'm all alone and maybe 20ft in front of me. I hear commotion coming through the brush, and, uh, all of a sudden this enraged baboon breaks cover like 20ft in front of me. And he is really angry. He's baring his teeth. He's pounding his fist on the ground. A baboon can kill a man. It stands four feet tall.

Speaker 2

[00.00.24]

Hello, and welcome to one off Travel Stories. I'm your host, Andrew Towers. Trynna hear each episode I chat with someone about one of their favorite travel stories, that one story they've told countless times to friends and family around the dinner table. We'll hear captivating and sometimes unbelievable travel tales and learned a little bit about the locations where they happened. Today we're joined by James Michael Dorsey. James is an award winning author, explorer and lecturer who has spent three decades researching remote tribal cultures in over 50 countries. He has a separate passion for work with cetaceans as a naturalist on whale boats in California and Mexico. A parallel career he's pursued for over three decades. These two passions combined have resulted in over 800 published essays and articles and four books. There's lots of information on his website James Dorsey. Com. What they've also resulted in is a lot of amazing travel stories. And today he's going to tell us one of his favorites. He's going to tell us about visiting western Tanzania. He was in search of a specific tribe, the Hunza tribe. He'll tell you more about them during the podcast. And without giving too much away, let's just say he ended up on a hunt and the results were interesting. But let's jump into it and I'll let him tell you more. Hi, James, welcome to the podcast.

Speaker 1

[00.02.03]

Good morning. Thank you for having me.

Speaker 2

[00.02.05]

Yeah. It's, uh, I'm really I'm really excited to have you on. Um, usually what I like to ask first is, where are you calling in from? Where are you today? I

Speaker 1

[00.02.15]

live in a little town called Marina, which is five miles north of Monterrey, on the central coast of California.

Speaker 2

[00.02.21]

How beautiful. Beautiful. Um, obviously, it's, uh. I guess that that area is probably known for its lovely weather. How's it today?

Speaker 1

[00.02.31]

It's a beautiful summer day, which is a little unusual here. We usually have a lot of wind, but it's calm as can be right now.

Speaker 2

[00.02.38]

Oh, that's that's excellent. Um, so, James, I, I, uh, I've been doing a little research about you. Um, and I know, and I assume you live there, and you've been you're sort of deep into cetaceans, which are whales, dolphins, um, those types of marine mammals. Um, is that what sort of brought you to Monterey? And you still. Is there a lot of focus on on that sort of research and activity there?

Speaker 1

[00.03.06]

That was part of it. Yeah. I've worked on the water most of my adult life. I have two separate professions, actually, remote exploration and the cetaceans, and I kind of alternate between the two. But yeah, that was a big factor in moving here. That and uh, I used to live in LA and couldn't stand the traffic anymore. So that's one thing that drove me up here. And I feel like now I'm living in Paradise, so it's great. I, I love it there. I've been through many years ago, I did the, the typical drive down the coast, um, at that time San Francisco down to LA. Um, is that the the Pacific 101 or is it the. Yeah, just highway one?

Speaker 2

[00.03.48]

Yeah. Highway one. Sorry. Thank you. Um. Absolutely gorgeous. Uh, absolutely beautiful. Is it is it where is the again, this is many years ago. There's an aquarium like a famous. Is it Monterey? Where there's the big aquarium.

Speaker 1

[00.04.02]

It's in Monterey, about five miles from my home, and I go there often. I'm a member, and in fact, I'm on a volunteer waiting list to help them track wild otters. So we'll see about that in the future.

Speaker 2

[00.04.15]

Super interesting. Yeah, I again, I was young, I remember seeing it must have been the seals, the big tank there swimming around. That was kind of a formative memory for me and coastal wildlife anyway. So anyway, a beautiful place. Um, I know you've got a story for us today that actually has more to do. And maybe this is what you said, splitting your time between cetaceans and explorations. Um, you've got you've got a book out specifically on your time with cetaceans, but you've also, I believe, got books about tribal cultures. So, like, how did you end up with this split and interests, um, throughout your life?

Speaker 1

[00.04.56]

Uh, well, I've always been interested in cetaceans. That that came first, but I never really worked with them until I was 40 some years old. Um, the exploration part came about when I was offered a membership in both the Explorers Club and the Adventurers Club, and that opened up a worldwide network of people. And I started traveling with some of these guys who were into documenting vanishing tribal cultures, uh, people that had no written languages. And that just fascinated me. I just got hooked going out with other explorers doing that, and eventually made it almost a full time effort. And I've produced three books, which are all personal narratives about my interaction with these people in places in remote tribal areas.

Speaker 2

[00.05.42]

I've done a lot of reading about it, but I haven't had a lot of, um, chance to speak to folks that I guess more on the anthropologist side that have done the work and done the exploration. So I've got a bit of a trend then with the explorers Club. You'll be my second guest from the Explorers Club itself. I that was I asked uh, it was J.R Harris the first one him to explain it. But maybe you can give your like what is the Explorers Club in your words.

Speaker 1

[00.06.11]

Uh. Well, mostly membership is based on, uh, fieldwork, uh, publications, scientific research, that sort of thing. Um, I don't have a degree, but I have written and published three books and about 800 essays on these vanishing cultures, which got me a fellowship in the Explorers Club. Uh, the Adventurer's Club that I also belong to is quite different. Um, that's based on pure adventure. It's not any exploration or anything. So like I said, between them, it gives me a worldwide network of people that can help me on these expeditions and point me in the direction I want to go and make local entrees for me, because I can't just walk into some of these remote villages unannounced. The people would either disappear or get an arrow in the back. So I always do a lot of homework before I go somewhere.

Speaker 2

[00.07.03]

And that that makes sense. That makes sense. Um, I find it incredibly interesting, really motivating as well to do some to do travel. That is a little I mean, just just a little different than I think what we, uh, we might see these days on reels and TikToks and whatnot. So, um, yeah. That's incredible. Uh, as I sort of prefaced with earlier, I know you've got a a story to tell. Um, and this podcast is about long form storytelling of a travel story that was sort of unique, um, made an impact on you, um, or on on the folks that I interview. So with that said, um, yeah, I'd love to jump into it. And a great place to start is usually context, you know, tell me what year it was, what year it was, or what year you're taking us to, uh, what, uh, what you were up to and, and where you were traveling to.

Speaker 1

[00.08.00]

I believe it was 2009, but I am not exactly sure of the date at this point. It was it took place in western Tanzania, and I specifically went there to find what has been called the last true hunter gatherer group in all of Africa. They're known as the Hadza or Hadza people. And so I wanted to see these guys. Um, if anybody knows about the sone Bushmen in Namibia, the Hadza are their cousins. And they both speak the speak this Khoisan click language that, you know, like, it's very strange sounding. So I wanted to see these people. And, uh, a friend of mine who has a safari company in Africa, his name is Ellen Feldstein. And he set me up and gave me a driver and a car. And, uh, from where I was in western Tanzania, I was on a place called Lake Lake Iasi. From there, I could see the southern caldera of Ngorongoro Crater for a reference point at geographically. And we drove all night to get into this forested area where we knew these nomadic houses were living. Uh, we got to this big open field, and, uh, the driver just stopped and he pointed in a general direction. Because being nomadic, there's no guarantee of where these people are traveling. I was even told when they make a kill, the entire clan will relocate to the dead animal rather than bringing it back. That's how nomadic they are. So we drove all night through a heavy rain, and, uh, I started walking through the bush and I started seeing rock formations that had animal skins drying on them. I ran into a few women who totally ignored me, and I climbed up this ridge to what looked like a big cave entrance. And when I came over the top, there were six hods huddled around a tiny fire. And being inside that cave and where I was just made me feel like I was looking at first man

Speaker 2

[00.10.00]

before. Before you get too deep into the story, I'd love to know. Um. I'd love to know how you. So. How did you come across this? I mean, maybe it was just in your research. Maybe you've known them forever. How did you come across this group? The Hadza? Um, known as the last true hunter gatherers. And what do you do to sort of prepare? I mean, you talked about, um, speaking to someone you knew. Maybe it was through the Avengers clubs, but, like, preparing for a trip like this. I know you've been in a lot of them, but I'd love to know your sort of thought process, uh, going into the trip.

Speaker 1

[00.10.36]

Well, the way I found out about them was there was an old movie decades ago called The Gods Must Be Crazy. And it was a story of a San Bushmen who found a Coke bottle in the middle of the Kalahari Desert and decided God had dropped it from heaven, and he was going to take it back to God. That was the premise of this movie, and I was fascinated by that, because I learned that this little bushman ended up, uh, managing a hoodie, a farm for a British pharmaceutical company in South Africa. And I just started doing research on the sand People and found out that they had, uh, cousins known as the Hadza, who had broken away 3 or 400 years ago and migrated to western Tanzania. So these are two factions of basically the same ethnic group. And like I said, there they are listed now, as is believed to be the last two hunter gatherers in Africa. So that's how I heard about them, as opposed to, uh, preparing for a trip like this. Um, like I said, I have a friend with a safari company. He hooked me up with local people who went in and said, this guy is coming because I had to get permits to enter that land. These are right. Yeah. Um, they don't just let anybody walk in. They're protected, for one thing. I mean, outside diseases could wipe people like this out, so, you know. That that was a lot part of it. The rest of it is planning for food, because when I'm in these areas, I don't want to take a chance on getting ill by eating things. I don't know what. They are so right. I carry lots of power bars and trail mixes to live on if I have to, that sort of thing. And that's just basically the preparation. No more than that. Just that and being physically fit because there's no medical evac from these places. If you get in trouble, you're on your own.

Speaker 2

[00.12.29]

Hmm. I know you say you know, physically and there's no more than that. That actually seems like maybe you've done you've probably been doing it for a long time. From what I understand, that seems like a pretty long list of things to do to prepare, not just kind of getting on a plane and going, how much of that do you? So when you get there, do you have to organize all the equipment on on that side upon arrival?

Speaker 1

[00.12.52]

Normally I would in this case the the safari company took care of all that. I had a car, I had a driver, uh, they knew the general area where these people were. And so it was just up to me to hike through the forest and, and find them, which I did.

Speaker 2

[00.13.08]

And how long do you usually. Well, I guess in this particular case, how long did you how long did you think this trip was going to take? I guess you don't really know going in. That's the.

Speaker 1

[00.13.18]

Yeah, I don't really know. I usually allow myself several days of unplanned activities before I have a return flight from anywhere because, I mean, if a car breaks down or whatever. Uh, yeah. And most of this I was walking to. So, uh. You know you can only plan so much. The rest is pure adventure and exploration, and it's always a roll of the dice.

Speaker 2

[00.13.42]

Yeah, exactly. All right. And last question, and I'll I know I jumped in at a kind of an exciting point, but, um, you mentioned, uh, well, you mentioned disease. Basically the fact that, you know, we'll have different, um, exposure than folks that have been living in this nomadic lifestyle. How do you how do you avoid that? Um, yeah. How do you avoid passing? What's the general, um, planning around that side?

Speaker 1

[00.14.11]

First of all, I make sure that, uh, I test myself for Covid before I go in anywhere these days, and I wear a mask at first contact. Um, uh, after that, I. Since we're outdoors, I don't have to worry about that much. I'm not getting that personally close to these people. But one thing also that's very important is, uh, I know a lot of trekkers believe in giving gifts when they get to these places, and that's a huge mistake. I found out because you upset the tribal balance of things. You can't give one person a gift and not the whole tribe. And they don't understand that concept because they share everything. So I bring something. It's it's for everybody. You know, I made a mistake once of bringing balloons for children, and that turned into a huge debacle. And, uh, I don't do that anymore. So it's just a little pick up when you're when you're traveling in these places, what you can and what you can't do, and talking to other people that have been there before to find out customs, like, you know, some people, you don't touch them on top of the head, you don't show the soles of your feet to them, that sort of thing.

Speaker 2

[00.15.20]

Yeah. So important. These are cultural. You have to know the cultural nuances to go into these areas. So I mean, when I'm not traveling, I'm reading. If I'm not reading, I'm talking to people. This is just my life and I love it. Um, to me, it's it's ongoing education, learning about all these other people around the world. Most of them are going to vanish in my lifetime. And so my writings are giving them a little public voice to tell the world, hey, we existed. You know, the people come and go, and and the great anthropologist named Wade Davis said that 50 years ago, there were 35,000 languages spoken on Earth. Today, there are fewer than 6000. And of those, fewer than a thousand are being taught in schools.

Speaker 1

[00.16.07]

So in the last speaker of a language dies, an entire culture goes with it. And in Africa, they say, with these oral societies, that's like a library burning. All that knowledge is gone. So that's what I'm doing. I'm kind of doing a little part to keep that knowledge alive and share it with the world.

Speaker 2

[00.16.25]

That's beautiful. I. It's a good point. Um, a lot of I mean, because we live in a digital age and we already pass through much more print, but a lot of these societies, they pass on their knowledge, their history, their culture through through stories, correct through oral tradition, like from one person to another.

Speaker 1

[00.16.44]

The the more remote areas you go into, the better the storytellers they have, because that's the way of life. They're not sitting around a television at night or on the internet. They're telling their stories and they're missing their legends to each other.

Speaker 2

[00.16.57]

Yeah. Uh, I've got to track someone down to have them on the podcast, because that's the kind of, uh, storytelling that I'm looking for. Um. Great points. Um, and as I said, so I jumped in. But I think that this gave us really interesting insight and context. So by this point, I mean, you've been doing this before. You've got your steps laid out. You know, you're prepared. Um, so anyway, we can jump back into, I believe you were walking into a cave and there were some people huddled around a fire. Yes,

Speaker 1

[00.17.31]

there were six hods. There were diminutive people. They stood little over five feet tall, wearing assorted castoffs, I would say, from whatever previous trekkers may have left there. And they saw me at first and kind of ignored me. So when that happens, I just start photographing until somebody tells me not to. Okay. Um, and so I was approaching these guys, and as I got closer, they kicked out the fire with their feet and they motioned for me to come close and squat down. And using friction, they started a second fire. They wanted me to watch this. Okay, so

Speaker 2

[00.18.09]

it did. Then they kicked out the second fire and they pointed at me. They wanted me to make a fire. I was being tested before. They were just going to say, come on in, all right. They wanted me to make the fire. So I used their fire starter and a stick and friction and a little moss. And I made a small fire. I thought, this is cool. Now I'm in. And because this is kind of normal in a lot of these societies, they do test you a certain way before they just accept you. And I thought, okay, great. Well, now they pulled out a bone pipe full of ganja. And also, I have found over the years that a lot of entrees to a remote society means you have to sit and smoke with the headman. Sometimes it's tobacco, other times it's ganja or got or whatever the local is. This happened to be really powerful stuff, and I did not want to get stoned at that point, because I was there to document what they were doing. But if I didn't do this, I wouldn't be accepted. Right. I smoked

Speaker 1

[00.19.09]

with them and that that just kind of got out of hand for a while. The longer I was there, I realized these guys smoke around the clock. It wasn't just a ceremonial thing. I mean, they smoked enough to kill Willie Nelson, and I was I couldn't do it.

Speaker 2

[00.19.23]

Their tolerance was a different place than yours. Yeah.

Speaker 1

[00.19.27]

I wasn't expecting all this, so I passed two tests. Now they pull out a bow and arrow and they want to see me shoot. Okay, these guys are really five feet tall. They're pulling a six foot bow that'll drop an elephant in its tracks. They're so powerful. I could barely pull this bow, but I managed to embed an arrow in a tree, so thank God that was the third and final test. They said, you know, motioned for me to follow them, and they took off like rabbits. And they're all carrying bows and arrows. The only way I kept up with them, because they lost me quickly. I was following their tracks in the mud because it had rained all night. And every now and then one of them would pop out of the bushes and give me a hand signal directing me which way to go. So I thought, okay, there they I don't know where they are, but they're keeping track of me and I just want to get there in time to see them make a

Speaker 2

[00.20.16]

kill. Before you move on from the three tests, because that's fascinating. I'm curious, when was the last like, when was the last time you had to make a fire from from friction or shoot, shoot, bow and arrow like. Yeah, probably around 1970, in my army training, uh, I had to make a fire. Bows and arrows. I've shot sporadically over my lifetime, but I've never been an archer. If you say that. I mean, all I had to do was show them that I could actually do it. And I stuck an arrow in a tree, and that was good enough for them. I mean, they didn't. Expressive.

Speaker 1

[00.20.54]

Yeah. They didn't expect me to, uh, hunt with them. They just wanted me to pass these things to say, okay, this guy's legitimate. He's not here. Just some tourist, you know? Yeah, yeah, I mean, I maybe did it, you know, at camp. So that's why I was wondering. I feel like most people now, you take for granted the fact that, you know, we'll have a lighter or matches or something. Um, so anyway, my feeling was you must your heart rate must have been up, like, okay, let's. Oh, yeah. Yeah, let's get this done. And these guys were dead shots. I mean, I they also carried wooden tipped arrows. Uh, if they're not sophisticated enough to do metal work. So they get, uh, metal tips for their arrows from a local tribe called the barb eggs. And these are blacksmiths, and they they make their arrow points for these people in exchange for meat and pelts. Yeah. And, uh, then the Hadza coat them with a neurotoxin made from boiled roots, uh, that they have locally. I'd have to look up my notes to get the name of this stuff, but it does work. It's a paralyzing, uh, toxin

Speaker 2

[00.22.02]

for paralysis. It's.

Speaker 1

[00.22.04]

Yes, it is. And so anyway. Now. I'm following these guys, and I'm getting signals of, uh, which way to go. And suddenly everything's very quiet. I'm all alone and maybe 20ft in front of me. I hear commotion coming through the brush. And, uh, all of a sudden this enraged baboon breaks cover like 20ft in front of me, and he is really angry. He's baring his teeth. He's pounding his fist on the ground. A baboon can kill a man. It stands four feet tall. Before I had the second to react. This animal's got two arrows in it. It's on the ground. It's twitching because the neurotoxin is killing it. And I realized at this point, there's a heads on either side of me with another arrow knocked in their bow, ready to fire a second time, huh? So I didn't even have time to react at that

Speaker 2

[00.22.57]

point. Did you know they were there? The Hadza?

Speaker 1

[00.23.00]

That's the point. I never knew they were there. They were. You know, they were giving me hand signals every now and then and then disappearing again. But they were paralleling me without my knowledge. So all of a sudden I'm shaking. I mean, I'm going into shock because I realized I was almost attacked by a wild animal that could easily kill me.

Speaker 2

[00.23.22]

Yeah, those they're powerful. I've, um. yeah. And

Speaker 1

[00.23.27]

following right on top of that emotion, I started getting extremely angry, realizing these guys had set me up. They had used me as bait because they knew where this baboon was hiding, and they put me over there so it would attack me where they could kill it. So I went from shaking fear to rage at what they had done. And then all of a sudden it occurred to me that I just got the greatest travel story I could ever have. And so I wasn't angry anymore. At that point, I thought, I'm alive and look what I've got here. This is amazing. One of the most amazing experience I've ever had, and I don't think anything could ever top that. Um,

Speaker 2

[00.24.09]

being bait,

Speaker 1

[00.24.10]

a photo of me with these guys is the cover of my third book, and it's called baboons for lunch. Uh, because that, uh, after they killed the baboon, they decapitated it. They smeared the blood on my face because I was part of the hunt. They field dressed it, took it back to the cave where they seared it, and I had to eat the first piece, which was tough and stringy and tasteless. But I did it.

Speaker 2

[00.24.37]

Okay. But the fascinating thing about this story was about. Two months after I returned home, I was just reading this long term DNA study that I believe was published by Stanford in 2007, that claimed this distinct group of Hadza people were possibly one of three three separate generic groups in which all of mankind is descended. Wow.

Speaker 1

[00.25.03]

No, I don't know if that's true. I haven't done any more research on that to validate it. But if that is. I mean, my own family set me up as bait on a baboon hunt.

Speaker 2

[00.25.16]

So

Speaker 1

[00.25.18]

that's the story.

Speaker 2

[00.25.19]

I'm. I'm super curious. Like, it seemed like they they acted quite quickly. Right? Like you, as you said, you came in, you were taking pictures. They sort of tested you. And then immediately they were like, okay, let's let's head out on the hunt. Like they had a plan. Obviously they had a

Speaker 1

[00.25.36]

plan and they used me. They, you know, they they wanted to see what I was going to do. I mean, how did I react if I had backed off everything and didn't smoke or didn't shoot an arrow, I they probably would have walked off and left me in the cave. So, you know, I have to be interactive with these people if I'm going to get the story. And in this case, I got a great story.

Speaker 2

[00.25.56]

How, um, how long did you end up spending with the heads of people?

Speaker 1

[00.26.01]

Only a couple of days. That that was the end of a of a longer trip, and I kind of tacked it on and I saw everything I could. I mean, there wasn't any more to see. Uh, I could not communicate with these people, which normally I have a local interpreter, but in this case I didn't. It was just me and them and using hand signs and what have you. And body language is the best I could do. So I got what I needed and then I left.

Speaker 2

[00.26.30]

Other than using you as bait, did you feel safe throughout the time interacting with them?

Speaker 1

[00.26.36]

Absolutely, yeah. I have never felt threatened by any remote tribal people anywhere. In fact, most of them are at least curious about me. Uh, or at best, a lot of them. Like I traveled in the Sahara with Tuareg nomads. They considered it an honor that I wanted to enter their society. And they dressed me in their robes, and they gave me a camel. And I rode with them through the Sahara. That that they were happy to do that. And that's mostly the reaction I found from these remote peoples.

Speaker 2

[00.27.11]

That's interesting. Um, yeah, it. Yeah, it makes sense. I mean, I think we end up hearing about the 1 or 2 tribes where something bad goes wrong, but otherwise it makes sense that they would just be as curious as maybe you are, um, seeing someone arrive from a faraway land, as it were. And a lot of times there's just no interest at all. I mean, they just tolerate my presence because their world is so small. Uh, they don't know what to talk about. They don't know questions to ask. They're they they just, you know, one thing I do run into is why I'm away from my family. That's something hard for these people to understand. Why you would leave your family if you didn't have to. And another thing is, I always carry a small locket with a picture of my wife and my dog in it, and when they ask me, well, where's your family? I show them this and and they think I'm joking because I have a picture of my dog.

Speaker 1

[00.28.12]

You know that that's not family. You eat those. But, I mean, fortunately, I don't know of any people who still eat dogs. Uh, but. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Too long

Speaker 2

[00.28.24]

ago. They eat what they have too, right? Um, yeah. Uh, did you stay for the, I guess maybe the 1 or 2 nights you were there? Did you stay with them? Were you in the village or did you have.

Speaker 1

[00.28.38]

No, it was just it just inside the cave there. We just slept on the ground. Okay. Yeah. There was no houses. Overall, there's something like 3000 houses. Right? And of those, probably 300 of them are still the hunter gatherers. The rest assimilated somewhat into the modern world. They have taken over prefabricated housing the government's provided and food and all that kind of stuff. But this little particular clan, and they're broken up into subclans. Uh, that's the ones I spent my time with. And there were only six of them in this group, so. Gotcha.

Speaker 2

[00.29.18]

And they're all in Tanzania?

Speaker 1

[00.29.20]

Yes. Western. The western part. Right. It's an area called the Manara Highlands.

Speaker 2

[00.29.27]

Okay. And I think you touched on this a few point, and it's something I've read about before. Um, but maybe you can can give your view because you've definitely done more research and you've, you've met with these, these peoples. But, uh, from what I understand, they don't their society is not hierarchical the same way that ours is. And I think that goes back to what you were saying about gift giving. There's not necessarily like one person to give a gift. Everything is shared. Is is that sort of what you found?

Speaker 1

[00.29.57]

For the most part, yes. These people have no chiefs. Um, most of these remote societies been very egalitarian, I think. Mhm. In fact, uh, when I was with the Tuaregs in the Sahara, I was surprised to find, um. I mean, they're Muslim, but they're the only sect in Islam that I know of. When the men cover their faces and the women do not. Mhm. And, uh, the women are absolutely equal with the men. In fact, they handle all the money. Uh, they're treated with great respect. It's there's no classes between the people. They're all the same.

Speaker 2

[00.30.38]

Interesting. Yeah. I always found that, um, again, I've looked into or researched it before, and it seemed like it just some point in society when you get large enough, you need to organize a bit more top down for decision making. But if you're in small, tight knit, mostly family groups, um, it's just interesting that things stay more egalitarian and there's more sharing that happens. And to your point, like. It would seem crazy to them that you would leave your family. Um, if if that was the kind of society that they lived in, right?

Speaker 1

[00.31.15]

Right. I mean, most of these people I have visited have no concept of what I'm actually doing. Then I'm. I'm there to try and tell the world. This is what I saw about these people and this is what they do. And to them, it's just life. So they don't really comprehend why I'm there. I'm most of them just accept me.

Speaker 2

[00.31.37]

Yeah. So, um, after after that, that was that. Towards the end of your trip, did you, did you have a long hike in or out, or was it pretty seamless?

Speaker 1

[00.31.48]

It was just a couple of miles. I made my way back to the clearing where the driver dropped me off, and we had arranged a pick up time and all that. Yeah, and what I forgot to mention, while I was first looking for these people, I came upon this big, thick tree. It was hung with animal skulls. So that's how I knew I was in the general area. And at night they would put their bows and arrows on these skulls to hang them there and take the power from the animals they killed for themselves. That was the belief they killed that animal. So now they have its power and they get it by hanging their bows on this tree. It was like the voodoo soul of the clan.

Speaker 2

[00.32.30]

Right, right. I mean, um, just coming across. That would be. It would leave an impression, I think, if I was walking through the, well, Sahara or forest or whatever. Um, and I saw a tree with skulls and bows like that. That would be so quite something.

Speaker 1

[00.32.48]

It is, and I have a vast image collection. So I, I give talks and presentations about this all the time. And the people are kind of amazed by most of the trips I've been on. Uh, and like I said, uh, there's not a lot of people doing what I do, at least not that I know of

Speaker 2

[00.33.08]

so well. It certainly makes for some amazing stories. As I said at the beginning, I it's very interesting because, um, you know, this isn't just not the typical travel that you hear about every day. Um, and I like I mean, I personally am very I find the research angle of the travel very fascinating as well. So getting out there with sort of a purpose, if you will. Um, yeah. Yeah.

Speaker 1

[00.33.34]

For me, this is simply ongoing education. I know I never went to college. I don't have any degrees. I'm not an anthropologist. Although I guess you could say that's what I'm doing. Uh, and the most amateurish way. But, uh, to me, I'm just gathering knowledge as I go through life, and I don't ever want to stop doing that.

Speaker 2

[00.33.59]

I love that, and, uh, you know, I'm an amateur, so, um, maybe I don't have the right perspective, but it doesn't seem that amateurs to me. You did, uh, you did pass the three tests, and, uh, I don't think that most people would have been able to just, uh, start a fire and, uh, shoot the arrow, and, uh. Oh. What was the second one that they made you do?

Speaker 1

[00.34.23]

Oh, I had to smoke with them.

Speaker 2

[00.34.25]

Smell smoke. That's right. Most people could probably do that one. That's. But, uh, holding their own would be a different story.

Speaker 1

[00.34.34]

I think you can see this. This is the firestarter that those people used to create a friction fire. I kept this. This is a fire starter from the two hunter gatherer group in Africa. One of my prized little mementos from this trip.

Speaker 2

[00.34.50]

So cool. And because we're only audio, it's a it's basically a little a little stick with a, with a circular groove in it for the, I guess, the other piece of wood that you would rotate back and forth quickly, and it has a little gap where you put a little starter underneath that. Hopefully I'm explaining that correctly.

Speaker 1

[00.35.11]

Yeah. You can, you can watch castaway with Tom Hanks and see how he makes fire. I mean that that's that's the whole thing right there. It's a lesson in fire making.

Speaker 2

[00.35.22]

Amazing. Well, um, I, I'm curious to ask before we wrap as well. Like, what are are you still are you still doing trips like this? Um, that was that was 2009 ish. Um, it's 2024. Like, what are you up to these days?

Speaker 1

[00.35.38]

Well, I'd have to say my my travel these days is a little more luxurious. I, I have made so many of those trips sleeping on the ground or of sleeping in the sand or in a mud hut. Uh, I now prefer hotel rooms because I'm getting up there in age. I'm still traveling a lot. Uh, and and I'm focusing more on the cetacean end of things because, uh, I am paying a price at this point. I have pushed my body hard on these trips for many, many years, and so I can't travel that way as much as I would like to anymore. But

Speaker 2

[00.36.14]

I want us. All right?

Speaker 1

[00.36.15]

Yeah, yeah, it was all worth it. It's been a great life, and I'm very grateful that it's still going.

Speaker 2

[00.36.22]

That's amazing. Before we, um. Before we wrap the second time, I'm saying it, but, um, I know you work with cetaceans. I know you also have a book that you released. Uh, the lagoon, if you want to say any any words on that. I think it's also really fascinating. We didn't really talk about it today because we were focused on, uh, you being bait for for a hunter gatherer tribe, but, um. Yeah, again, if you if you want to mention a few words about it, it's it's super interesting work.

Speaker 1

[00.36.51]

Yes. It's a memoir of 22 years. I was a resident naturalist in a gray whale sanctuary in southern Baja. And, uh, there are three great lagoons in Mexico. I worked in San Ignacio Lagoon, and it's the only place on Earth where wild animals in their natural habitat routinely seek human touch. Hmm. Most people say that's not possible, but I've asked people in many years if anybody can dispute that, please do so because it's a fact and this is going to be next. Next February will be my 27th year going down there. I now lead an annual travel with the author trip because the book is a memoir of all my time in that lagoon, and it's a definitive history of central Baja, the natural history of the indigenous people. And it's kind of a definitive work on great whales, too. So that's the whole package right there. And it's called The Lagoon, and it's available anywhere on any major bookseller.

Speaker 2

[00.37.50]

That's amazing. Well, thank you, James. Thank you for publishing and doing sort of this work. I can speak personally that I, I read I read books like yours. Uh, it's also how I found J.R., and I find it super motivating to do, um, other types of travel, but just to be curious about cultures and, and places to visit that I wouldn't have thought of. And you've got two separate streams of really interesting work. So thank you and thank you for being on the podcast and and sharing with us today your your story.

Speaker 1

[00.38.25]

Thank you very much for giving me the opportunity, I am grateful.

Speaker 2

[00.38.29]

All right. Have a great day, James. You too. A big thank you to James for coming on the podcast and telling us this wild story. Um, I'm really starting to appreciate these adventure type travel stories you can really get into, um, some unique and amazing scenarios. Please go check out his website, James Michael dorsey.com, and definitely check out his latest book, The Lagoon Encounters with the Whales of San Ignacio, if you're interested in the topic. If you have an amazing travel story that you'd love to tell, uh. Also please feel free to reach out to me. It's a one off travel stories dot com.

James Michael Dorsey

Explorer, author, lecturer

James Michael Dorsey is an award-winning author, explorer, and lecturer who has spent three decades researching remote tribal cultures in fifty-eight countries. His personal narratives give a small voice to those who otherwise would vanish from the earth with few people ever knowing they existed. His separate passion is working as a cetacean naturalist on whale boats in California and Mexico, a parallel career he has pursued for three decades. These combined journeys have resulted in over 800 published essays and articles and four books.

He is a former contributing editor at Transitions Abroad and has written for United Airlines, The Christian Science Monitor, Lonely Planet, Perceptive Travel, California Literary Review, Colliers, Los Angeles Times, BBC Wildlife, BBC Travel, Geographic Expeditions, Wanderlust, and Natural History, plus several African magazines. His fourth and latest book, “THE LAGOON” is a memoir of his years spent in San Ignacio Lagoon in Baja. He was the SOLAS Grand Prize winner in 2016. His work has appeared in two volumes of “Best Travel Writing,” from Travelers Tales and the Lonely Planet Literary Anthology.

He is a member of the American Cetacean Society, a fellow of the Explorer’s Club, and member emeritus of the Adventurer’s Club.

www.jamesdorsey.com