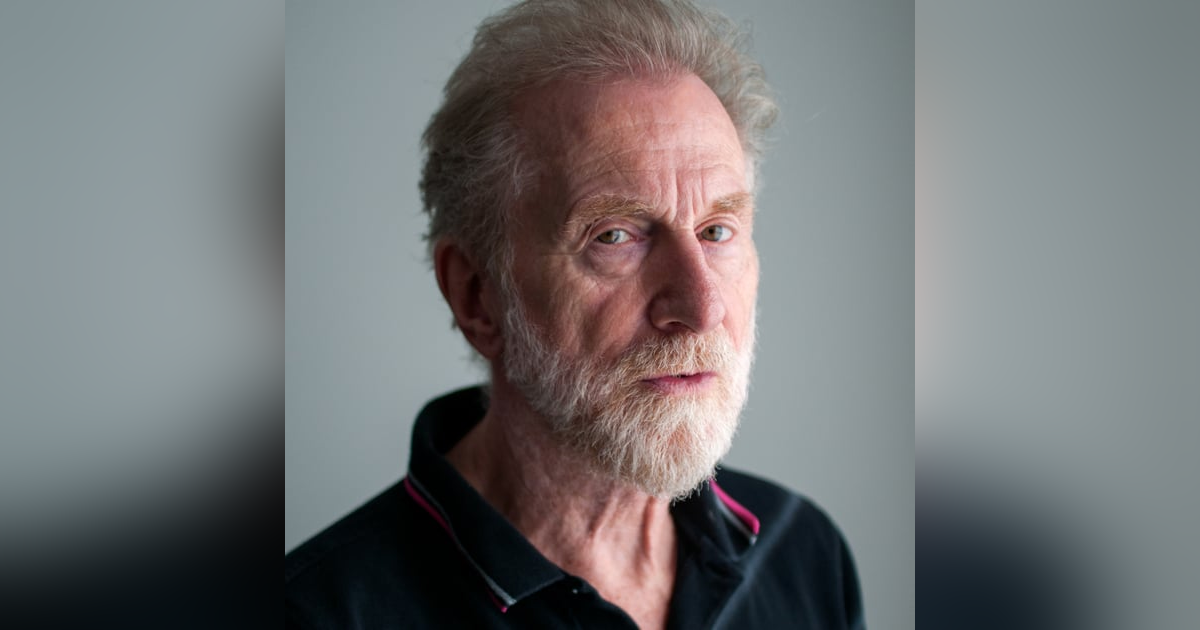

Andrew Loog Oldham

LP catches up with Andrew Loog Oldham. Andrew managed and produced the Rolling Stones until 1967, started Immediate Records, and then went out to lunch for many years.

The longtime manager and producer of the Rolling Stones, Andrew Loog Oldham promoted and nurtured the group's notorious reputation as the bad boys of the British Invasion, orchestrating their ultimate rise to prominence as the "world's greatest rock & roll band."

Andrew currently hosts "podchats" on his own podcast called Sounds & Vision. He's featured conversations with Mick Rock, Jerry Schatzberg, May Pang, Danny Goldberg and others there.

You can also read more about Andrew through his 3 books, STONED, 2STONED, and STONE FREE, all available on Amazon, Abe Books, and from your favorite book shops.

Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Lawrence Peryer: Good morning.

Andrew Loog Oldham: Well there’s an engineer called Glen Johns, have you heard of him?

LP: – Of course, yeah.

ALO: OK. And there’s a producer called Shel Talmy who produced The Who and the Kinks in the early – some early David Bowie stuff when he was Davie Jones. And he somehow had – Shel had a number plate from a friend of his and it was LP, LP1. And when John said, “Could I use that for a few weeks, the Eagles are coming into town and I want to look good?” And one of the first, it think it was probably Desperado, those things; at Olympic in London. Anyway Glen never returned the plates. Yeah, once an engineer, always an engineer.

LP: Well he wasn’t one of those white lab coat engineers was he?

ALO: No, he was not, no. he was – I'm one of you. Yeah addressed to, yeah hey, you know what’s the act we’re in this week? OK, that looks good, I’ll do that. Use the shadow, I mean look it’s not that bad, but there’s no – the light in Vancouver that way you can see I'm vaguely here. OK, good now back to where it was. The – no man – and he actually produced The Rolling Stones before I did, which was one of the reasons that when interviewed by somebody for me for one of my books, he said – and wrote him, he couldn’t produce juice out of an orange. Right? But he was very good friends with the sixth Rolling Stone, the – Ian Stewart who I technically got rid of, which is not really true. And he had recorded – are we on now, yeah we’re good?

[Audio Gap, 00:02:01 - 00:02:04]

ALO: He – because this bit doesn’t get – but as we’re celebrating – I was going to say, celebrating the anniversary of Brian Jones death. But anyway, oh God they’ll be down on me for that. The – Glen and Stu, Ian Stewart who was the sixth Rolling Stone, knew each other very well. And there was a very forward looking studio in London at that time on [Portland Place] above the BBC, called IBC. And one of the owners was an orchestra leader and the other one did the business and Glen, who was an apprentice there, persuaded the studio, they said, “Listen, give this group I like, The Rolling Stones, time – free studio time to do three or five things. And what do you want?” And they said, “Well we want an option on them for six months to go and place their stuff with a record company.”

Now this is when they were under the mantel of an impresario in very loose quotes called Giorgio Gomelsky. And he – and that was really, I think the studio was very – you know there weren’t many studios in the middle or August of 1962 who would do that, you know give you free time, don’t – or even were thinking in terms of let me – all right we’ll take a chance on this, with this rhythm and blues or whatever. And then I came along and cut to, so we don’t spend the whole time just discussing this particular aspect of them. I'm training Brian Jones on the corner, now look I’ve – we’ve given him 90 pounds because we work out, that’s what the studio will claim they’ve got in it. Oh, – I was – The Rolling Stones and I were already in love and they go, “Oh, by the way, we’ve got this small problem, this contract with this IBC Studio.”

“Oh, well thanks for telling us,” fortunately Brian Jones was the only one who’d signed it, so I'm training him on the corner – “These actors got to be – I'm so fed up with these Rolling Stones, man. This band they’re not professional, they’re really not – I’ve got an opportunity to go and join.” And I said, “Brian, don’t say the Yardbirds, but have the words, the Yardbirds in your mind,” so you look believable and one of them is really good in the room, right. And he goes in and I'm waiting on the corner and they take the money and then The Rolling Stones were free. But –

LP: ALO, why do you think the label – the studio owners at IBC had – what would make them say we’ll take that six-month option? Other than it being easy to say, were people at the time thinking there were bands everywhere and everybody might make it or –?

ALO: – No.

LP: I don’t think that was the case –

ALO: – No, it’s true, it’s early, it’s like – this is like God where did I meet – I met them April of ’63, so they had made this tape in and around October or November, I'm not even sure of Charlie Watts was on it, because I don’t think he joined until January. Bill had joined the previous – because you don’t ask when you meet a group, “How long have you been in the band?” You’re a band, you know. And – no this was very forward looking, either they liked Glen, either Glen was nice and pushy or I sort of think – I kind of think because one of the owners of the studio was a band leader, that might’ve helped, I don’t know, diminish his prejudice against this new wave, this COVID wave that was coming up to take over the music business, you know.

LP: Equally as filthy and transmittable.

ALO: Indeed, indeed.

LP: What became of Gomelsky?

ALO: Gomelsky, well Gomelsky was sort of like – he was great, I’ve known, and I'm sure you have, people from Austria or Germany in America who just kept the accent because it helped the gig, you know. And Giorgio was one of those, Giorgio was like, I don’t think it would anymore, man but then, oh well how charming. But Giorgio was full of revolutions and all this stuff, but I don’t think he could ever handle anything that would – could play into – in a room of more than three people. Yeah I think he ended up – he only died a few years ago –

LP: – He already came to the states.

ALO: Yeah in New York, yeah. And he used to hold gatherings, I mean we’ve met, great, we met a few of those nutcases when I was doing the radio for Steven Van Zandt, you know they would – also from another universe, God bless you I’ll say. And he just held – I think he held fourth in New York, OK, he had Julie Driscoll and Brian Auger, he had that for the hip period. He drank with the right people of Polidor, which is how Robert Stack would go in, guy called Roland Reny, if you could go the whole – if you could drink all day with this guy, you had a deal.

LP: Fair enough.

ALO: And he lived until he was, I don’t know, close to 80, which is fine, he said approaching it himself.

LP: Looking to blow past it, I'm sure.

ALO: Yeah, right, exactly, exactly. But he –

LP: – Let’s not talk about your mortality, let’s talk about your immortality, I’d prefer to have that discussion.

ALO: OK. All right.

LP: Well there – and I’d prefer to not – I'm much more interested in you as a figure, who I'm a similar way, has been around and has always been – it’s very appropriate to me that you’re sitting there lurking in the dark, in the shadows on this call because you’re always there and you’ve always been there. And you – and like locusts you surface every few times a generation. But you're always in the background and sometimes in the foreground. And one of the things that’s interesting to me, I’ve gone back and retroactively created a narrative where we have several things in common. And one of the things –

ALO: – Connecticut.

LP: Yeah Connecticut, yeah. And having spent time in the – in [unintelligible 00:08:54] –

ALO: – Oh, oh dear, right. OK. Did you live in Connecticut?

LP: I did, I grew up in Hamden, Connecticut and – which is a little bit south of Langford, a suburb of New Haven. And when I was a wee teenager, I had a band and what I learned was at a few weeks, I took the audio engineering course at [unintelligible 00:09:18] I could get free and discounted studio time. And so it seemed like over the winter investing eight or 10 weeks once a week to go do that, would pay off in free studio time. And so that’s what I did and recorded my band and a bunch of other bands –

ALO: – Yeah, I lived in Wilton from ’69 to ’73, that’s how I got to Connecticut.

LP: And how did you roll up into Connecticut, what – why Connecticut?

ALO: Let me think about that, oh, OK, yes I was a tax exile. Although I, excuse me, although I was not with The Rolling Stones by that time, we still had the same problems in that we spent everything. Let’s look as big as the Beatles, whatever. Right? And the British government wanted 88 or 93% whatever it was after you paid the third in America. But we were paying that, no mind, we had other problems, what I should just call, the problems of 1967. And so by ’69, OK, they went to different places and so and so. I went to – I love New York, man, I mean I had – from the time I got to New York in 1964, I kind of knew that in the Americas in general, I was home because – I’ve decided it was because my father was American.

And so I just felt great, man, you know. Engineers are not in white lab coats, you know they are enjoying their gain, they’re not – it’s not a 9:00 to 5:00 thing, there is a certain passion there with this music business almost like the seventh art of America, as opposed to what it is in France. But – and then ironically I only got the closing thread to this story later, I had done a deal for me and The Stones on a friendly collection basis with a producer called Bob Crewe. And just because, you know let’s go where we know the people. Along came a gentlemen called Allen Crime he was given that name by John Phillips. When I bumped into John Phillips on Third Avenue after he had come out of jail, opposite a place called Yellow Fingers in New York on Third Avenue opposite [unintelligible 00:11:54].

So we went in there to have a – they were [unintelligible] for drinks and had a drink and he said, “By the way,” he said, “Guess who I was inside with?” I said, “Go on.” He says, “Allen Klein,” and he said, “I call him Allen Crime now.” So John Phillips and Allen were in the same downtown Manhattan, Allen was making the 22 salads a day he had to make and then he was allowed his phone calls, but – to run his empire. And – I mean one of the – there were many, many advantages to Allen Klein, I think one of them is that once you’ve known him, you know all you need to know about Donald Trump.

LP: He was a Trump of his day?

ALO: Well it’s a New York thing. You know it’s not a criticism, so hold the lawyers, Jodi. It’s just an actuality, there’s a certain, what are they saying about me? Did he recognize me?

LP: It’s funny you say that, that people don’t realize or I think America at large doesn’t realize that as east coasters and as New Yorkers, we’ve been dealing with Trump for a lifetime and everybody knew exactly what he was, how he was, there’s been no surprises really that you would take a New York gangster and put him on the international stage and he’s going to behave exactly as he been –

ALO: – Exactly, exactly. I mean there’s another great figure in our business, a guy called Donnie Kirshner, right, now when I was speaking at Allen Klein’s funeral, I saw Donnie in the audience, first it’s the red tie. They’ve all got red ties and blue – dark blue suits and I saw him there, so I threw him into the bit when I was starting to name drop. People are – and he just came up to me and, “Oh, ALO, I'm so glad you remembered me,” you know but that’s the wonder of New York, what is he saying about me, yeah.

LP: Yeah. The place in New York where I didn’t see you and I supposed it might offend you, by telling you it disappointed me to not see you was at the Hall of Fame induction. And I always wondered if you made so much noise about going because that’s what you do, and it was a way to generate more attention to your induction or if you were truly put upon by the notion of the Hall of Fame.

ALO: Well, to start with, I don’t do honors’ well, I – even when my trainer is training me, if they paid me a compliment, I fuck up the next four repetitions.

LP: Sadly I know that, I know that about you –

ALO: – I need a witness and then they go well done and then I'm out – them I'm sort of out of sync. And basically it’s the same thing Steven Van Zandt from the best of – for all good reasons, I mean he was in the business of resuscitating whatever he decided I was. And – but from all, from the heart and all good [unintelligible 00:15:08], I'm going to get you into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. I'm going to get you in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. I said, “Don’t bother,” right, now I knew him very well, but I didn’t want – I didn’t even know myself what on earth I could say, I won’t handle it well. Because if you coupled it together with the fact that it was now no longer a private party where Keith and I could go up and Keith would be my backup when I would go out to Village Old and go, “Billie, please to meet you,” to start with. But how do you write songs by yourself?

And he didn’t know what the fuck we were talking about, because to him that’s his day job and he does it. To me and I think somewhat to Keith from knowing how Keith – promote knowing how the process had started for him and Mick and for others. It was curious, man, because, when do you stop? Who – what brick wall, what white wall in your apartment or ex-wife or ex-business manager said, “That’s great, it’s a hit,” do – So I was, in that I am totally about the power of the song, protecting you from everything. I was curious, but he just like, [unintelligible 00:16:39] what the fuck are these guys talking about? But anyway, so that was – so in those days filled with three bodyguards and – on the stage and the actual musical free for alls at the end, I could’ve handled it maybe in that environment.

I’d like to turn down an honor from the queen because it’s just a fucking family business, man, you know. As it is, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. And I didn’t – OK, the year before, they were seemingly allowing the people like Quincy Jones and Lou Adler to pick who was inducted and who did their music. When I spoke to very sweet people at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and I said, “OK, who is going to play the music of the Beatles and The Rolling Stones?” And they said, “I wouldn’t worry about that, there’s not going to be any music.” So I thought, oh we’re going to be like the accountants at the Academy Awards. And Peter Asher, American’s, accept those who have lived it in England and then they’re going to – don’t have an idea.

I mean it’s the difference between Brooklyn and Manhattan or thing – I may have taken advantage of him when we were both 16, when I put on an R & B, a rhythm and blues night in Hampstead Town Hall claiming to be a charity. There was no rhythm and blues except in the post stickers, so we got the town hall for free. My partner and it was a guy called, Peter Meaden who was the first Who manager for five minutes, he called them the high numbers and so on and so forth. And Gordon, of Peter and Gordon, tops the bill as mark conquest. And Peter and Gordon close the first half of – which time we had 57 pounds and Peter and I decided it might be better to leave. So we got our comeuppance and when we tried in the king’s road and lost all the money, but there you are, and I don’t know, man, I don’t know the guy.

Just because he’s English and he’s got red hair, you know and I tried to get Keith, right, when they were having that problem, they had to stop the tour in Australia – I mean this is just data, it’s not – probably not answering your question. In the end just to rile people, I said, “I really don’t want to be inducted with a dead gay Jew.”

LP: That answers my question.

ALO: There you go –

LP: – That answers my question.

ALO: And I promise you Brian wouldn’t mind.

LP: Yeah, yeah. Well I had read a quote where you said something to the effect of – and it’s so funny because you know I think more than most how these things land in print without the intonation, without the inflection, without the sense of irony or anything else. And the quote I read was, you said, no one asked me about whether I wanted to be inducted and no one asked Brian Epstein either. So I'm going to – Brian couldn’t make it to his induction and I'm not going to make it to mine.

ALO: There you go, all right. We made it to the [mugs], we made it to the t-shirts and [unintelligible 00:20:10]. OK, I do Pug Chats, right. And the premise of them, but the reason they’re called a chat and not a cast is because I do them with people who I know, right. And I did one about a week ago with Elliot Easton of the Cars, wonderful fella, right and he – and it worked. But I'm sure it’s the same for you when you do these things, there’s – along comes someone with a remark and you go, whoa, I can live on that for a few minutes, a few hours, a few years, right. My favorite one was from the drug money runner in Columbia who was beating his wife up on the floor because she couldn’t – she was looking on the floor for a diamond in the shag rug, canyon-type carpet.

And he just – as he telling her to get ready, he said, “I told you don’t have tears for the things that don’t have tears for you.” Oh, that’s brilliant, I could live on that for 12 years, right. But anyway, with Elliot Easton, excuse me, we – in this thing we were discussing and so on and so, and he just said, “Look,” he said, “The two hours I'm on stage you can have for nothing, what you’re paying for is the other 22 hours.” I thought that was great, you know I mean he just had it simplified and I suppose I didn’t want the other 22 hours in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. I mean I told Steven for 10 years, “I don’t want it,” and it was not modesty, it was my reality.

LP: Yeah, yeah. How does it come to pass that in the – I don’t even like to call your life a career, I think of your – I think when I – and obviously I have not ever spoken to you before this conversation, so it’s all my perception and what I’ve decided in my head about you. But I think of you as one of these people that, you have a life and a career and it’s the same thing, that you’re this entity that, in a way similar to Keith in that what you see is what you get. And that your life is performance and your life is not that different when you’re not on camera or on microphone. And I accept that I'm probably completely wrong –

ALO: No, no. I was speaking to a British actor a few weeks ago, [Darren Stamp], and we were talking about this thing we’re going through and he sort of said, “Well, you know ALO, I went off to India and you went –“ I said, “Yeah to the dealer,” so I sort of had 25 years out because of my addictions. By the way, I do want to discuss The Oral History of David Bowie written by Dylan Jones with you; whoa, what a page burner that one was, but – which I just read over the last week. And it – no I mean you – I'm lucky enough that the dreams I had when I was nine or 10 became a job, no not even a job. When I had, excuse me, five cars and I was still trying to impress my mother, and I took her out in one of them, the Phantom 5, and she got out of it and she still said, “Yeah but Andy, when are you going to get a proper job?” Well that’ll ground you, you know.

And, yeah I mean it’s pretty – you're pretty lucky when your passions pay the rent on enough occasions that – and if you're not, if you like money, but you're not driven by the accumulation of it, or – I mean we’re only eating one meal a day now, but two meals should do. It’s – I don’t mix out of basically a circle of people who are civilly blessed. I mean with this stuff that’s going on. When I check in with my friend, since ’64, ’65 and thereabouts, they’re all well because they’ve been living the same kind of life, this is not new to people my age or slightly older because even if we weren’t conscious of the detail of it, we grew up in it after the war. A lot of rock stars who will be nameless now have invented more of what they saw in the war than is possible, you know but you’ve got to answer those questions for the journalists as they do more interviews than I do.

So, but austerity, silence because our peers and our parents and our elders were not boring us to death with what they had sacrificed for us, but you could read it on their faces. And even though you didn’t know what you were reading at the time, it became apparent and if it didn’t become apparent as you grew older, and realized, oh what did I say straight for, my kids? You – through all this thing I can remember the face of my mother told me everything, still now with – so we’re kind of used to that. My youngest son said to me about a month ago, he said, somebody had told him that when this thing ran its course or whatever that airplane travel, because he was worried about the prices, was going to go back to how it was in the ‘80s.

And he was asking me to remember what it was like in the ‘80s and I thought, well – I said, “Well,” because I was basically in New York then, right and Columbia. And I said, “Well I could always afford to travel business or first to Columbia, but I did have to schlep to Europe, I couldn’t pay those prices.” Thank God for a gentlemen called Freddie Laker, who had those, well cheaper airlines because for like two years I had to go and visit my mother’s boyfriend, who was slowly dying. And so I think you could get on a plane for 175 or 275. But in many ways there are – there could be blessings apart from the awful ventilator mistakes, and the scrapings of the hearts, and the lungs and now we see a form of dementia is coming out of this thing.

But three drops of oregano, eight drops of vitamin D, not just now but every day for at least the previous 10 years and always, you don’t have to be sick, just take it, right. And it – we’ve got a – OK, I was a lecturer, I did a – I went to Thompson Rivers University from January to April doing a course on music called, Rock Dreams. It was meant to be 1952, 1954 to 1984, I got as far as 1967. Then you realize what you’ve missed and you think wait a minute, I really have to explain to them how people like Giorgio Gomelsky and [what we term] Robert Stick or Joe Meek and those – how records and how it was all done, so I spent a lot of time there.

But we had about 200-plus students and one stage I asked a girl to enunciate and she actually – she’s in the class and I'm doing the gig and they’re there. And I said, “Could you enunciate?” And she actually said, “Could I send you the question by text?” Now I'm not criticizing her; this is just the way that it is, you know when they had to write up their experiences over the 12 weeks, there were at least seven or eight who didn’t know the difference between w-h-e-r-e and w- – and wear clothes. And it became painfully apparent that – I mean after all, if communication is the key to whatever, right or basically to everything or the ability and the ability to listen. These kids, this quicksand called a telephone, I welcome these signs back, man I want to go back and stay in a hotel where they hire real people not actors and I can say, “Were there any messages for me?”

I know dream on, ALO, dream on. But I will create/continue in answering your other questions, I will continue to create my own world that I feel good living in, because it was based on [unintelligible 00:29:50] anyway.

LP: Well and to bring that into the other formative figures you just mentioned of the music business as we know it, and you had to explain that as part of your course. What were you and your contemporaries using as – what did you think you were inventing or what did you think you were doing? If you aspire to something more, you had a drive, if you had an ambition, what was it that you were doing –?

ALO: – No, no, no, you said two words that are just – they’ll trip you up, ambition and inventing. Any of us who thought that they were inventing something was shown into the side room or they fell by the wayside on their own later. Like maybe simplifying it and not wishing to be hurtful to those who [admire], but Brian Jones might be a contender for that. In that – OK remember I could never fully get what a musician got or what their mind was all about, so therefore I can explain Mick, but I might not be able to explain Keith. In that they had – my instrument was my mouth, you know and what came – how – what the key was that – of what came out of it. But no, man, Ok if you were in that whole – if you weren’t – if you didn’t own a car – so that your great grandparents had build by what is apparent now to the rest of the world is slave trading, and –

Did you see the guy of the company selling Oxycodone died of cancer at 65? One of the – today, yeah I just find that comically, he couldn’t handle the pressure, man, because inherited wealth is such a fucking slope, right. Unless you’re all peace and love. But I’d invent – if you think you invented it or if in terms of what you’re doing, you need somebody else to tell you whether it was good or not, you’re in trouble. And – no we were just getting out of the way of the future that had been promised us, which was not too good. We weren’t poor enough to be – to have been from the east end like the aforementioned Terence Stamp and/or his brother Chris who managed The Who and had the record company with Jimmy Hendrix.

So they may be closer to what you're saying, they might’ve had – they had more of a gutter to get out of than I did, I went to very nice orphanages. But – and they weren’t orphanages, they were high-end – my mother couldn’t afford to keep me at home, so I went to these kind of places, you know. And – or we weren’t – nobody was going to welcome us into jobs or into the city, I got my – sorry, you knew but you didn’t – I watch people on the street when I walk now talking on the telephone, there’s no difference between the way somebody speaks on the telephone who owns everything and somebody who is one week away from disaster, it’s the same bullshit coming out of their mouth because this is what the last 40 years has given us in terms of –

I used to say bullshit was something that God used to give to the fortunate few now it’s a worldwide disease. And so I say it a little quieter. But I was – I did – I had such a great read, man at the Oral History of David Bowie [unintelligible 00:34:11] – I found it terrifying. I mean, woo, I couldn’t have lasted in all of that, I can’t imagine being with the one you’re with and saying to her as you enter a room, “By the way, we’re not talking that one, we are talking to him, he’s useful.” I mean OK, one of the bottom lines was, OK when The Rolling Stones and I came to America, we couldn’t afford it. There was what was, we – the Hotel Astor, the – when – in the Bowie to freeze structure of Main Man of 1972, ’72, ’73, they came in and moved straight to the palaces.

It was straight to the Carlyle, it was straight to the Pierre, the Sherry-Netherland. That was unattainable and until Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey started staying in separate hotels, oy vey. I mean, it – just the – OK, none of us wanted to be Fats Dominick, we may have wanted to have the ease of how when he played – so the one thing that you’re really always looking for is the ones who win are the ones who understand the space like Dion. Right, I mean Dion is like an instrument in a band, I mean I watched him like 15 years ago in Connecticut actually in the Mohegan Sun sit there, stand there and decide when he was going to drop the next note in. But he was conscious of the playing and where to put himself in as opposed to Jule or anybody who graduated from the [Maria Carey] Gymnastics School of listen to me and you won’t catch me sing flat.

And Nick Cave, shame on you, you know you’ve made it OK for so many people to now sing flat. So one of the pleasures of watching that rubbish on TV the other night, because I do watch rubbish, was the cast of the Girl from the North Country. Well, I mean they might say, what are you talking about? Well actual voices that are trained to drop and breathing, you know I mean I was – if I had one question for Frank Sinatra, when he – in his swimming pool, swam for his breath, to help his breath control. What did he do with the headpiece? That’s what I wanted to know, you know and by the way, in terms of John Wayne being racist, I once was walking into the Beverly Hills Hotel with my wife and with a gentlemen called La Bruja who was one of those sort of Columbian drug kingpins.

LP: One of them.

ALO: One of them, but this one – you either look like Benecio del Toro playing a drug dealer or you look like the few could pass, looking like Persian princes. They – and this one La Bruja had it, right, woof and we’re walking in and John Wayne is standing at the top of the stairs with his Mexican girlfriend/secretary, Sharon and I said to her, I said, “Look, it’s John Wayne,” and La Bruja, runs ahead of us, up the stairs at the entrance of the Beverly Hills Hotel and he says, “Mr. Wayne,” and John Wayne goes into that and the handshake, right. He said, “I want you to meet two friends of mine, ALO and Esther.” And John Wayne said – put his hand out and he said, “Very pleased to meet you, I'm John Wayne.” I mean come on. OK, so that’s what makes it work very worthwhile.

LP: Yeah, I wonder what John Wayne did with that hat when he went in the pool, you didn’t ask him.

ALO: No, I didn’t, I was so amazed at the – he wasn’t like so many with little bodies and big heads; he was John Wayne.

LP: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Tell me a little bit about when you had Immediate and you were making records on your own, was there anything the artists all had in common to you? Is there something you need to see in an artist or that an artist needs to demonstrate to you for you to put your passion into it?

ALO: Well my standards slipped with Immediate, there was one thing that they had in common it was that they were all children. And at that time you’re not going to realize that you have been spoiled by The Rolling Stones, you – because when that time goes and you’re faced with the small faces or the nice, see – I mean you know this because I know that you’ve been in close quarters with what we’re talking about. When people say to me, “Oh, God man, you got to spend three minutes with Keith, how was it?” I said, “Normal,” you know they were special when they went on stage, but – and they didn’t moan, I mean that’s so important, they did not moan. Most of Immediate Records moaned. I – basically – I formed it kind of, I was getting a little too high to go outside and deal with record companies, I was like laughing at them by now.

And high or arrogant or cocky or whatever, but I like the idea, I based – I had originally hoped that Mick and Keith and me could become a sort of [Hollandosier] in Holland by virtue of the way. I mean Mick Jagger had done an incredible job producing Chris Farlowe for me, that was – that produced a number one record. It’s very expensive, it was like one and a half Rolls Royce Phantom 5, which is not a sensible amount to be spending on an album, right. But it was a joy to behold because amongst other things he actually managed to get a British brass section to, for want of a better word, to groove, not to play like they were reading parts or you know – I went off Immediate Records –

I was spending my own money anyway and I was past – I mean that’s why I would admire people like Chrysalis or things who – because if you’re going to do that you’ve got to stay the course and turn it into a business and live happily ever after or whatever the phrase is. To me, when I get fed up, I leave or when I know I'm going to be invited to leave, I leave 24 hours before that request comes. Doesn’t tell you much about Immediate but I mean Clive Davis used to take the bus to work, please.

LP: When you said the artists it strikes me that it’s not that long of a time that it sounds like the conventions around being a rock star and the sense of entitlement developed so quickly. From the time of – you know you said you had the Stones who I take it when you say they didn’t moan, basically meant they showed up and they worked.

ALO: There you go, right.

LP: And in a short period of time it already became the idea of the coddled, pampered rock –

ALO: – Well, OK, it goes in very fast degrees, it’s like, OK when I would speak to another – a drug money runner, who was five or six years younger than me and go home and they – so peace and love, I said, “What are you talking about?” Before the guitars were like Bren guns, man, you know I mean, OK you went – the first thing is the public started taking drugs, that made – and the ramifications of the Vietnam War. I mean, I did – had a deal with Motown with Rare Earth in ’69 and my business partner at the time said, “Man, you got to go and find a group.” So I was down to the Westport [Grainery], you know the little thing in front of the Westport Seminoles where all those rich [4-f] motherfuckers were playing acoustic guitars and thinking, oh journey, you know and things.

And s I'm the first one that would pass muster and they were certainly on Rare Earth, you know and I had – was in such a mood about it, I called their first album already a household word. But be that – OK, but even a few years, because then that’s ’73, before that the public’s taking drugs, the people who are running the record company have decided we are not going to go away, so they get used to it and they start dressing for the part. And then came the dreaded word, advances, you know advances to acts, well – and also then on the technical side, which I’ve tried to steer away from all my life, no it’s just – [unintelligible 00:44:31] yeah I'm sure – you know maybe through your parents then, I was born when nothing came with instructions. So once things started coming with instructions I was lost, you know open a package instructions, oh, you just had the thing that you bought before.

But the dreaded thing about advances is that it applied – I felt like Morris Levy by the time I’d finished with Immediate Records. Like artists who’d sold a 180,000singles, 80,000 of which we had bought into the charts, were certainly believe in their own bullshit of what their mother or their girlfriend was telling them. “Oh you’re screwing me, man,” you know I – “I know I saw –“ the Small Faces sold 68,000 albums of Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake in England, that was it. But now you’re also dealing with the seedier side of journalism that – I mean one of the reasons one of my books later only didn’t work in eBooks is because people wanted the physical books to sell on eBay. So it’s all a learning curve, isn’t it.

And advances and then of course at the end of the ‘60s you’re getting [unintelligible 00:45:53] and people who’ve got us to spit on, us to copy, the dream – the illusion of what they thought we were to copy and look what chaos that brought you. I mean, you know it’s all – look the song is the living common denominator, I eight, nine, 10, 11 months ago here in Vancouver went to see Lionel Richie, I was in heaven, the songs. Only if you’re not clear in our prejudice can you deny the songs. Doing what the same job as Vera Lynn did or the Sex Pistols did with God Save the Queen or Sha Na Na. Whatever it is there is one of the great rewards of it all, is when you see the effect a song, sung in the right key, sung with the right amount of strain or sexual tension or whatever, however you want to call it, it lifts people up.

That might be your job.

LP: There’s something incredible about a two or three–minute pop song when done right.

ALO: Yeah, yeah.

LP: Very incredible. Do you think that you have a particular simpatico with artists? What do artists recognize in you that draws them to you?

ALO: I think I try and become them. There’s a metamorphic thing, although I’ve noticed when I'm hanging around with people that I shouldn’t be hanging around with, in that I might adopt some of – their eating habits might not be good for me. But OK, the first moment was with a dead Jew who – I can – did you, no I won’t go there. Did you read in the papers about – well I will. And you can cut out what you’d like. About the dog that was buried in England, just in the last week? OK, it had a, what do you call it, those things, headstones, right? Had a headstone and they’d had to dig the headstone up and remove it – the dog was buried in 1902, because the dog’s name was the N word.

So I'm sending this to a few friends and things like that and I said, at the end of the conversation, I said, “Yeah, but you see the great pleasure is without any problem we have been able to use the N word,” in the same way that one of the joys of New York in the – you know there was Tom Wolfe’s Park Avenue and Tom Hanks and the book Bonfire and all of that. And all the other people that one knew at the end of the – well that you met who – in America who had made it with Doo Wop or singing on the stoops and whether they were Polish, Italian , Jewish or whatever they would say, but we’re all the N word, that it was a collective thing. When did we – did we notice a change? OK, there’s a wonderful song by Dion singing with Paul Simon on Dion’s new record and it’s a homage to Sam Cooke and it’s talking about the song, the lyrics are just great of being on the road with him in 1962.

And how it changed as they got further south in terms of the hotels they could be in or not be in and we had the same experience with Patty Labelle and the Bluebells in 1965. And – but anyway I got to use the N word again, you know because come on, you know we all want to be Chris Rock. Why not, you know

LP: Dion’s an interesting character because on the one hand, he’s not widely talked about in the pantheon, but on the other hand there’s people whether it’s Little Steven or you’ve talked to him, you’ve mentioned him now four times in this conversation, there’s certain – there’s people that Dion really impact and the fact that he’s still around and working is fascinating to me. That he really – his importance, I don’t know, it just can’t be denied and I can’t reconcile the impact he had on his generation and the kids that grew up with Dion. And then if you’re not of that era, it’s almost like he doesn’t exist.

ALO: That’s right. Yeah. He – hey maybe because he started heroin early, no he – when he was 14, man, I mean that was life in –

LP: – So he fucked up his own legacy –

ALO: No, no, no, no, I'm joking about his – he – no, I mean hey we don’t know. The only important part is his pipes, his delivery, his sense of himself and what he does and his ability to still deliver it. I mean, OK, on that – it’s very dangerous, people shouldn’t be making CD’s, you know there’s – I'm – you can’t – OK the one with Jeff Beck works, the one with Van Morrison works, the one with Paul Simon. There’s another thing by him and Paul Simon and I never thought I’d be spending this much time on Paul Simon, but great records and things like that, but he could’ve been Carl Reiner. But Dion, if you have sensed it because you knew what he was doing – you knew he knew what he was doing from a distance, that there was something that was there that you better respect because he’s respecting the craft that –

And it’s not genius, it’s not this, it’s hard work, it’s a craft, something has dropped, some essence has dropped something in your hands, you haven’t discovered it, you’ve been given the ability to use it. And knowing that you didn’t discover it is what stops you from going insane. If you think, oh that was me, you’re in big trouble. And this was by part of the nuts and bolts of the course I did because I really was trying to tell the students, it doesn’t matter what you’re doing, whether you're going to be a carpenter, an accountant, what – an IT salesman, or whatever the thing is, the same rules apply to – I’d also just make sure the woman you marry is prepped first.

LP: You teach them that in the class do you?

ALO: Oh, yeah.

LP: I have one other question I would love to ask you and that is, as someone who has been there from the birth of a lot of this, if not all of this, and it was such a youth phenomenon, what’s your take on watching rock and roll and rock and rollers age? And how does it strike you to see some of the artists whether it’s Dillon’s new record getting rave reviews, which it seems he managed to pull one out every 15 years that he adds to his pantheon. And then does a decade’s worth in between that nobody pays attention to. Or obviously the Stones and The Who on the road or McCartney out there. How does that strike you, how does that all land for you?

ALO: Well you see, the Stones on the road is basically like the Rat Pack with guitars, you’re getting the – you're not getting an old man trying to write young or try to be relevant. He knows what – they know what they did is relevant and they’re giving it to you and they’re having a great, hopefully a great time doing it, they obviously are, look at the sense of humor of Charlie with that thing they did with the blind drumming thing. Right? I mean that was just fucking immaculate, right?

LP: That was terrific.

ALO: It was just incredible, right? But I will – I’ve had quite a few people say, “Oh, man Bob Dylon, thing like that, you’ve got to listen.” No I won’t listen to it, OK. These are, I use the word and its context, quasi sensitive times for all of us, when I walk around South Sari and I run across husbands walking their sons and I feel like I should be introducing them to each other because their life before has been work, work, work, work, work and now they’ve got this time and so on and so forth. But to your question, I'm not interested in what – I'm not saying this about Bob Dylon, I'm just saying this in general, what an artist in panic, because they haven’t got the forum – I mean somebody was just down for wife beating because he’s not on the road. What the fuck is he going to do?

And so I'm not necessarily – I think we’ve got enough of a job right now keeping ourselves on course, I'm not to be able to have what I had going to see Lionel Richie here at the Roger’s thing when I'm sitting next to this black couple from – where, Seattle. Right? And when they heard that I had actually seen –– I was by myself because you can get a good seat, right. When they heard that I had actually seen Luther Vandross, they thought I’d went to heaven, man. You actually saw – and I was like, yeah that tub of lard, like – but give me the reason. Is one of those three-minute records we’re talking about, like Forever, right. And – or Exile, Kiss You All Over or whatever.

But that I don’t – I'm not interested in the angst of it and listen to me. I'm not saying that that’s what Bob Dylon to start with, I have to admit, I admire the aura more than I admire the content. I feel the same way about Bruce Willis, I don’t go and see Bruce Willis movies but I like him.

LP: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Glad to know that a Bruce Willis exists.

ALO: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. It means you can get above the title.

LP: – [In a word] for you.

ALO: Bobby Cannavale or whatever his name was in Vinyl couldn’t.

LP: Yeah, yeah. I’ll tell you what, that guy was born out of time, I think if he were an actor 30 or 40 years ago, he’d have – more people would know his name, yeah.

ALO: That happens – I mean but then you have the other guy, the guy who was in the three – the thing, he played – he put on weight and played the fat cop, Sam Bottoms, no not Sam Bottoms, Sam Rockwell. OK, there is – there’s certain things that work that I could compare, how do you pronounce that gentle – Bob Cannavale or what is it?

LP: Yeah, Cannavale, right, yeah Bobbie Cannavale.

ALO: OK, Bobbie Canavale, OK, good. As compared to Sam Rockwell, it’s no different that there isn’t a take – you take someone into your family or you don’t, that is one of the bottom lines. It’s the same way as when there were gay performers like Liberace or others I won’t because they’re living. But – or even Elton John, OK, before he came out or before what. The wife or the girlfriend is going, oh. See we were trained early with Johnnie Ray, a husband, his antenna knew that Johnnie Ray was not competition even if it was all subliminal. He wouldn’t resent his girlfriend liking Johnnie Ray or his wife liking Liberace or, oh Elton John’s so great, it wasn’t competition in the house and there are those elements, you can only experience them.

My mother, you know the one I like is – this is early, early, “Oh no the one I like is Keith.” I said, “Yeah, why?” She said, “He likes dogs.”

LP: Nobody who likes dogs can be that bad, right, that’s –

ALO: – There you go, right.

LP: I get that, yeah that’s funny. So what’s next for you, are you in a secure location in Vancouver or what are you – what’s life hold for you?

ALO: I'm on a plane that goes to South America on September the 3rd, Argentina and Columbia and Cuba seem to have similarities, I think it’s because the population is one way or the other, grown and live with the military, which means in the long run that you’re more likely to follow orders. Shame about where you are is there’s no general.

LP: Just a wanna be.

ALO: Yeah, I mean you have what you had in 2009 and how it was handled, it was handled quietly and with dignity. In south – anyway, I'm on – I don’t know if the planes will fly and also we don’t know what – we know that when the country that supplied Columbia with the most stuff recently was Turkey. Where is the reservoir of stuff? I mean fortunately my family is – they – both my youngest son and my wife are in Columbia and that’s the best place for them for the first round, one, two and three of this. I decided on my equal residence because I am more British than Columbian, but I'm in British Columbia. So it’s fine, man, you know. We – it’s just I have said my life was formed by the ‘50s and that’s what gave me the groundwork, now I’ve got to make sure that’s true, because that’s what we’ve got.

LP: Yeah, it’s fascinating to talk to people who grew up in the years immediately following the war. I don’t think Americans realized that the post-war period for England, really it went on for decades, it was not business back to normal by the early ‘50s or even the late ‘50s or even the mid ‘60s. it took decades for England to get its footing again and you can argue it didn’t have its footing for very long after.

ALO: No, it didn’t, yeah. But when you’re Prime Minister, while he’s in school it’s decided that he will be the Prime Minister; the system has not changed. And when I look at – I mean when I was 11, I went to Germany for the first time and I kind of, in present day language, almost thought I was on the set of Star Wars, because it had been rebuilt in terms of what America and the [MASU] plan or whatever it was, what the agenda was whereas England was still one up, two down. But out of that, I made the mistake of watching a documentary on the ‘50s last night, on a songwriter called Lionel Bart, who wrote Oliver and a lot of hits for Cliff Richard and things like that. And I think I’ll stick with my memory, my memory is personified by Daniel Day-Lewis in Phantom Thread that is the way I’d like to remember it, OK.

LP: Fair enough. ALO thank you for making time to do this.

ALO: Thank you.

LP: It’s really a pleasure.

ALO: It’s been edutaining as Graham Greene said.

LP: Isn’t that all we can hope for at this point.

ALO: All we should work for, yeah. Thank you very much indeed.

LP: Yeah and maybe we could talk off – this – will it stop recording, Craig or do we – you can just edit out if we –

[Audio Gap 01:03:57 - 01:04:04]

LP: I just wanted to connect with you over Keith and Jane. If you think of it, if you have a chance, phone Jane and surprise her. Don’t tell her I said anything to you, but yesterday was my birthday and she always does, she sends gifts and when I reached out to her, she said she was having a hard few days. And so I don’t know, maybe she could use to hear from some of her friends –

ALO: OK, good, no I do, do that with her, but I mainly do it by email and – because that’s like – but I will take that onboard and I will do it because he’s still got to be a tough fucker to work for. Anyway, apart from whatever else, yeah look who was born on December the 18th, you got Keith, Allen Klein, Steven Spielberg, Brad Pitt, they’re all tough motherfuckers, you know one way or the other.

LP: – Well you’ve got to throw Bobby Keys in there, I don’t know if he was very tough –

ALO: – Yeah, I’d rather not, there is the underbelly of each side, also [unintelligible 01:05:18] guitarist Elliot Easton’s the same, but hey – yeah. And he’s fascinating, I mean, well when you're born Elliot Goldstein you usually are.

LP: Yeah, right, right. I'm looking forward to hearing that conversation because I - they were a fascinating band too, they could write a great song.

ALO: I loved – because I spent time with Ben Orr, right. And even then in the ‘80s you didn’t go where did you come from, what’s the history of – ? I mean one of the devastating books to read was the, can’t remember his name, but one that wrote a very good book on Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. I didn’t know who the fucking Mudcrutch was, right. And that suddenly – and I had an interesting time with Tom Petty about seven months before he died, right. And if my – I went and did his serious radio show, now he may have lived off the Pacific Coast Highway, but he brought the trailer trash with him; I mean the [coffee urns], would disgust you, you know, I mean just the coffee urns. But yeah, it’s like being in the Four Seasons in Seattle in 2005 with Charlie Watts and he had this huge fucking tear with tea bags in it.

I mean, you know but the thing with Tom Petty is someone comes along and says, “OK,” – I mean I was spoiled with The Rolling Stones, they – what I meant about they didn’t moan, they didn’t – apart from Brian, but then again I kept my distance from him except when we were high together. But they did their own dirty laundry amongst themselves, I mean I didn’t know, for example in ’65, mind you they were being quite pragmatic, what can fucking ALO do about it, right? But when they were starting to have problems with Brian, they didn’t call me up and go – they took care of it, you know. And the – but hey Jane, she’s not – no I always stay in touch with her, but I will make a point of doing so now. But sometimes in these days, you’ve got to make sure that you don’t call somebody when you’re having a tough game.

LP: That’s right and unload all your shit on them.

ALO: No, because somebody else’s tough days going to make yours tougher. I’ve had – I’ve completely realigned what my physical activities are and I'm doing – OK, I’ve got this great heavy metal young base player as a trainer, because she doesn’t give a fuck, I mean it’s just clean. And she’s trained, she’s really well trained, she’s got degrees in everything, she – and she’s very good. And I’ve gone back to chewing gum because basically the big benefits of chewing gum is – are the lungs, which are our vulnerable place, one of our vulnerable places at the moment and the spine. But you know that was interesting one of the things that we saw – when you asked me the question and I got – I now managed to closet off better the difference between – because I don’t take any notes and what the new Rolling Stones music.

I know that Charlie Watts doesn’t, so why should I? but the difference between that and then attempting to – we’re all in the business we despised, not despised, but laughed at, but we never laughed at the discipline, we always recognized the discipline. And in those times we always recognized the ones who weren’t holding anything against us for having to move over slightly to let us in. I mean, I only recently – it came to me like as a jewel, I said, “So, you know why they paid us reasonably properly in the ‘60s?” And says, “Why?” I said, “Because they stopped paying the people I'm the ‘50s.” But Connecticut, man, I was in jail in Bridgeport, you know when there were no Latin’s then, there was Italians, blacks and whites.

LP: Yeah Bridgeport was a crazy fucking town, yeah.

ALO: Yeah. But it had a great –

LP: – So it’s – and it had – there was good music in that part of the state, I don’t know how much you know about the history of the Connecticut live scene in the ‘50s and ‘60s but there was a whole circuit that started in Bridgeport and went up through Naugatuck, basically followed the river up to Waterbury. And there was such a circuit back then of – and everybody – I talked to old timers back then, everybody played up their Coltrane, it almost had an extension of the chitlin circuit, there was a whole black music industry in that part of Connecticut that’s fascinating, really interesting –

ALO: – So New Haven, the black part of New Haven was fascinating then, you know I mean the people who worked in that old hotel there, the blacks who worked in the hotel were just fucking great, I used to be there in the ‘70s and ‘80s. And I [unintelligible 01;11:06] OK, he had one great, potentially great artist a lady singer called Christine Ohlman. But she fell in love with him and she never whereas if we look at say when you're looking at an act, you’re looking at who has the kill factor, there’s got to be a killer. And I take it this year we’re celebrating Robbie Robertson. Like – but if you don’t have it, then if you fall in love, you decide you then devote your life to that man and you never get out of – and I'm not, hey, love will keep Neil Sadaka together or whatever.

But – yeah exactly. I mean she had an incredible fucking voice, man. When I was looking for groups to put on Motown and Rare Earth, I remember from the Wallingford – and I was very comfortable there because he wasn’t going out, he wasn’t going anywhere.

LP: Mm-hmm. Did you do the – were you behind the live broadcast from there? I know there’s a very famous Fleetwood Mac broadcast there. No, you weren’t involved with that?

ALO: No, I can’t remember the name of the guy who did it. There were so many people who used to be drug dealers who then went into doing radio broadcasts. Great, you know.

LP: All the same clientele.

ALO: Yeah exactly, it was just amazing, OK I got it. There we go, yeah.

LP: The family, are you in touch with the family? Is the studio still running?

ALO: No, we fell out rather in the same way that Steven Van Zandt fell out with me. When he did – [unintelligible 01:13:10], he did [unintelligible] when I wouldn’t do the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, he actually sent me an email saying I'm canceling our friendship. Because he’d never been hurt so much by anybody, now we know that’s not true, he’s a guitarist.

LP: Well I was going to say, he had a very lucky life then if that’s the deepest he’s been hurt.

ALO: Right. But no I – yeah you’re quite right, I only met a lot of the people who went – came through [unintelligible 01:13:49] there are a lot of talented people. I used a lot of musicians from [Doc’s] Wrecking Crew on to patch up what all these fucking expensive musicians hadn’t delivered for me on a record I did with Donovan in 1974. I used them to overdub parts where it [unintelligible 01:14:12] just Donovan. But I had a good time there, because – but it was fascinating because in ’71 to ’73 the kid in the gutter in Westport was probably the richest kid on the block, the junkies. I mean when I was in The Pigpen in Bridgeport there was this one kid, I thought what the fuck is he doing, joining me at the back of the cube and the Italians and the blacks with the sink in the morning, right.

But he was going to the same place to be arraigned as I was the next day, Westport, and it was his like 15th time for smack. So never mind this epidemic now, but if I was in the [unintelligible 01:15:03] I’d figure you’re all fair game anyway. But –

LP: – The thing about the rich kid living in the gutter, it always – it reminded me of how St. Mark’s got to be for a while there, where I used to live in the East Village and right around the – you could tell when all the high schools got out for the school year, because St. Mark’s would fill up with homeless kids who looked like something out of Blade Runner the way they dressed. And then by Labor Day when school went back, they all disappear and it was clear they all came down from Connecticut and Long Island and slummed in the street all summer, that was their summer vacation away from mom and dad. And then would go back home and go back to school.

ALO: Yeah, OK. I mean the history of – I'm reminded of – in ’64 and ’65 in London on the Club Cabaret Circuit, not folk, you had the Simon Sisters playing with their dainty little acoustic guitars, sort of – as if Joan Baez was playing in a society club. But they all had all that money to come home to. There’s a great book written by a woman called Suzanna Moore, I think it’s called Miss Platinum, I have just finished reading it. And she comes from a very wealthy kind of all – quasi-wealthy fucked up family in Hawaii. So when she got her entry into Hollywood, and she would be hired as a script reader by Warren Beatty because of her legs. It’s all logical to her because she’s lived in – she’s grown up in madness, you know but the book is great because this woman has the gift like the aforementioned Graham Greene.

She knows how to iron the words flat, so that Warren Beatty is no more important than a car rental, it’s all even, there’s not, oh like – but that’s a very good book. And the woman just has this just obvious gift to – and it’s very interesting because her experience is nothing phased her because she came from a mad – a sort of, what I would call, mad, I mean it would’ve been made for me. But her family trained her for Hollywood in the same way that one of my sons is [unintelligible 01:17:44] so I have no surprises because I was Mick Jagger’s father for four years. I'm sure –

LP: – He’d love to hear you say that, I'm sure he loves that.

ALO: That’s the first time I’ve said it that way, so you know but there are – I don’t sit there and decide if I'm going to speak to you because of my astrological chart, but there are certain characteristics in people that can be vaguely undeniable. They will behave a certain way or are prone to or whatever –

LP: – Yeah could almost be counted on to.

ALO: Yeah there you go.

LP: Well Andrew, it’s a pleasure, I hope that someday we get to do this over a meal or across from a table.

ALO: That would be great.

LP: Safe to be in each other’s presence.

ALO: Yeah exactly, exactly I would look forward to that.

Andrew Loog Oldham

Visionary and Mensch

In 1965, Tom Wolfe famously dubbed Phil Spector America’s first tycoon of teen. Great Britain in the 1960s had its own version with Andrew Loog Oldham.

Similarly eccentric, Oldham sported a one-of-a-kind mix of flamboyance, fashion, attitude, chutzpah, vision, and business smarts. As co-manager of the Rolling Stones from May 1963 to September 1967, and founder and co-owner of Immediate Records from 1965 to 1970, he helped shape the future of rock, and certainly turned the music industry in the United Kingdom on its head.