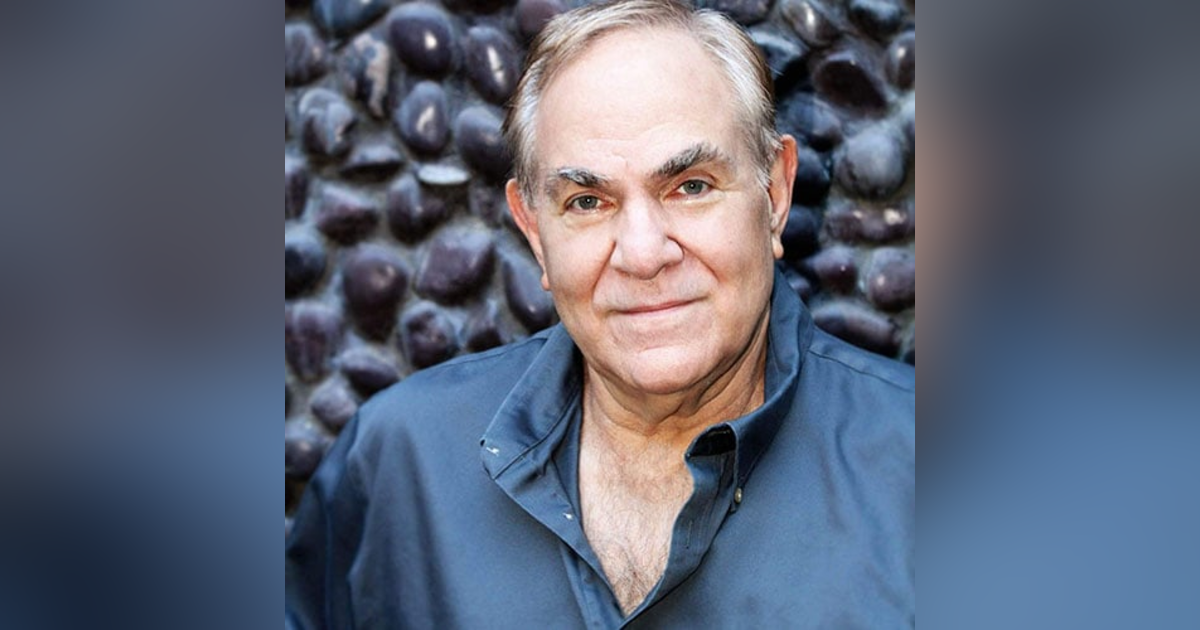

Ted Cohen

In this conversation, LP discusses Ted's history, the early days of CES, the early days of the digital music industry, and more.

Ted Cohen is an American digital entertainment industry executive. Having worked in senior management positions at EMI Music, Warner Bros. Records and Philips Media. Cohen is currently the Managing Partner of TAG Strategic.

Cohen currently chairs the Visionary Committee for MidemNet, served on the NARAS (Grammy) Los Angeles chapter Board of Governors as well as the National Trustee Board and currently co-chairs the Grammy Technology Committee. Cohen serves on the Board of Directors for the Neil Bogart Memorial Fund, Lyricfind.com, and Music.com, and works in the music and technology education programs the Grammy In The Schools Program and MusiCares. Cohen also served two terms as the Chairman of the Mobile Entertainment Forum Americas in 2006 and 2007.

Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Lawrence Peryer: Thanks for making time.

Ted Cohen: My pleasure. There's been a lot going on this week, you know, with the proliferation of online conferences.

LP: Yeah.

TC: You know, I literally have been jumping from a Zoom session in one conference to a Microsoft Teams conference in another conference. It's been crazy.

LP: Well, my perception of you for a long time has been that you basically – you've done obviously the physical world version of that for years. All right. You've been – you've worked that circuit, and you've been somebody that people have wanted to hear from for a long time. Are you find you're – are you attending more conferences as both a participant and a speaker? Like, how's it changed for you?

TC: Well, first of all, you have access to all this. So I mean, there's, you know, the ability to drop in on a webinar. I mean, we have both probably been getting webinar invitations for the past two or three years at least. I think there's more stuff out there right now that is interesting, and people want to talk about whether it's – you know, what's the new normal. You know, what's the future of live concerts. You know, is – where are living room concerts and virtual concerts going to fit going forward. There's all of that stuff.

I have to be honest, and most people who know me know this, I've been doing this I hate to say almost 40 years in digital. We started a digital – I met Wozniak and Jobs – I met Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in 1977 in Chicago at the Consumer Electronics Show when it used to be in Chicago before they moved it to Vegas, with the intention of going back to Chicago. And then they went, "Why go back?" But I met them in '77 in a hotel room, and they were – they basically unzipped a brown zipper case, and this is the Macintosh – you know, this is the Apple computer. It's going to change the world. And they looked like two homeless guys. But Warner owned Atari, and I started hanging out with the Atari folks.

So I won't go into all of that right now, but basically I've been part of a bunch of people that have been looking at what we would do and what we're doing now. We formed a formal group at Warner Music in '82 with Alan Kay, who invented the graphic interface at Xerox Park. He left Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, joined Atari. And in '82, we started this group to look at what was going to happen when the CD came out in '83. How was a digital format going to affect the music business? So we talked about streaming. We talked about downloading. We talked about burning CDs.

The average net speed at that time was 300 bits, not 300 mg. A blank CD was $100. A CD burner at the time was $20,000. So and the average computer, like an Atari, had 16k of memory. It had a – one sec. And one thing I should have turned off in the background, every once in a while, if we mention the word "computer," there it goes. Yes, no, I don't need anything. Hey, computer stop. Computer stop. Computer stop. [laughs] Goodbye.

I will take one second, hi, everybody, to mute everything for one – I muted everything except these wonderful – OK. This should be better. I apologize, everyone.

LP: It's all good.

TC: We looked at, you know, an Atari computer in 1979 was 16k of memory with a cassette recorder as a drive. You know, five years later, a 20 mg hard drive at the Apple – at one of the Apple dealers on – in Westwood was $350. Not 20 gig, 20 mg. It – so it was crazy. We didn't have the bandwidth. We didn't have the processor power. We didn't have all of the tools, but the concepts we started talking about, and it was led by a guy named Stan Cornyn, who was just this amazing guy at Warner who looked at marketing – what if radio didn't exist, was always his preface. How do we let people know about music if it's not being played on the radio?

So we did a lot of consumer advertising. He's famous for this ad about Joni Mitchell saying, "We have 10,000 Joni Mitchell albums sitting in a warehouse, and that's a crime. Send us 10 cents, and we'll send you the Joni Mitchell album." [laughs]

So he led this group, and we talked about all of this stuff. So I'm giving you again one of my longwinded answers to a very simple question – do you attend a lot more conferences. I spend most of my time saying, yeah, we talked about that five years ago, yeah, we talked about that 10 years ago, or somebody will say we're the first company who has ever done such and such, and I'm sitting here going, no, actually, they don't realize that Liquid Audio did that in '98, RioPort did that in '99. You know, Apple didn't invent the iPod. They acquired it from Tony Fadell, who had worked at Philips and Philips didn't want the iPod, so he took it to Steve.

So I – literally, I'm leaning back a lot. What I'm trying to do now is click on things, go into things that I don't know about that I sit there going, "Wait, wait, wait. Run that by me again." Because as versed as I think I am most of the time, I love those moments where I literally have to go, "Wait, say that again." I meet the person later and say, "I heard you speak the other day. Could you run that by me again, and talk really slowly? Because I think I've got it." And those are better moments for me.

LP: Yeah.

TC: You know, there's a certain lack of looking at history. You know, when someone says we want to do an interview with you, talk about the future, I say I've got to talk a little bit about the past, where we've been to inform where we're going.

LP: Yeah. Is there an example of a recent topic that really caught your fancy or caught your wonder in a way that either you hadn't seen that take on it before, or it was just a new subject matter to you where you say, "Wow. I've got to dig into that."

TC: Well, it's actually really understanding how machine learning works, you know, because we can always say it's AI, and it's machine learning, and it learns whatever. How does it do that? So there's an old friend named Judy Stakee. Judy was at Warner/Chappell Publishing. And Judy and I have known each other probably for 25 years, and she's doing Sunday afternoon, you know, how to get a sync license for a commercial, for a movie trailer. And I happened to see again on Facebook Judy Stakee is doing a get your music licensed, so I clicked on it.

And there was a guy in there in the – talking in the comments about AI music. And there's a company called Amper that does, you know, machine learning music, and company is actually funded by – one of the investors is Hans Zimmer. There's LANDR that does, you know, machine learning mastering, so you don't have to go to Bernie Grundman anymore, but you should. But if you can't afford to go to Bernie Grundman, you can send your finished recordings to – you know, load them up on LANDR, and they get mastered.

Those are all great concepts on a high level. How does it actually work, and what is it doing, and what's the input? The person that I met on Judy's, you know, sort of Facebook Live thing was a kid – he'll kill me. A guy named [Nico Collorog], and he started saying he's a composer who taught himself machine learning to basically take stuff that he writes, and then put it into the system, and extend the pieces, or do variations on things that he's written. So he's approaching it as a composer, not as a neuroscientist. And I think that's the tipping point for all of this.

So I'm trying to learn a lot more about what goes into creating the right learning systems. I mean, there's anecdotes. Microsoft launched a chat bot about three or four years ago in Japan and China. It was very successful. They launched it in the U.S. It became a white supremist. They had taught it the wrong things, and it picked up slurs and whatever, and so now the chat bot is talking like it's part of the – you know, the White Panther party.

So how – what does this do, and how does this affect, you know, where we're going to go with music in terms of recommendation engines, in terms of getting me to stuff that I don't know. I mean, my big – I always give long answers, so I apologize. You know, going back to '99, '98, there was a service in – out of Boston called FireFly, and it was a very attempt at machine learning recommendation and personalization. It's gotten better and better.

Echo Nest also came out of MIT in 2006. They got acquired by Spotify. There's Musimap that I worked with. There's – again, I also worked with Pandora. In each of these iterations, what I was looking for is I love Coldplay. I love Steely Dan. I love Michael McDonald. I love the Doobies. I love Chicago. I can't listen to them everyday for the rest of my life. Give me something – if I like the Doobies, don't recommend Michael McDonald to me. I know that. But get me to something that's going to have that same emotional impact that I get from listening to those artists, and whether you like them or not, those are the ones that resonate for me. Jennifer Warnes is one.

So you know, how do we use these tools to enhance our life and not lean on them, you know, to run our life. So, I mean, that's one I've leaned in on. VR and AR, there's a company out of Poland that I'm – I just started working with called [Teddy Berry], which I love the name anyway. And it's an AR creation company that knows once they scan – I'm trying to think of something – let's say they scan the steps of the New York Public Library, they can have an AR character walk up the steps. And when it walks up the steps, the shadows are what you would see if it was a real person walking up or down the stairs, or sitting down. It literally – once it's mapped the environment, it's not just walking down Fifth Avenue or Madison or Sixth Avenue or whatever. If there's a car in front of it, it blocks part of the character. If there's a car behind it, it blocks the car. But also, if it stepped up on the car, it knows where it is in space. I find it fascinating. So it's getting realer and realer.

It's those – I don't know. I'm saying it's just a question, but I continually like to learn, and I continually like to be – I like that moment when I don't know everything.

LP: Yeah. Well, I think I'd like to take the conversation in both directions of time linearly. And I'd like to ask –

TC: – And I'll give shorter answers. [laughs]

LP: – No, that's fine. That's fine. But I would love to – on the music AI front, what – do you have a sense or are people talking about what the killer apps there, or what is the – what's the why around this technology?

TC: Well, I mean, some cases it's cost. I mean, so I'll give you two examples of AI. One I was working with a company out of Israel about eight years ago. We had a client called YouLicense. And we had approached Warner/Chappell at the time about building them a search engine to go through their category and identify and tag low-hanging fruit that – one of the problems is, is there's only so many hours in the day. So you're working at Warner/Chappell. You get a call from a church in – or a synagogue in St. Louis, that wants to use "We've Only Just Begun" for their fundraising campaign. It's a $500 – you know, they don't have the money.

So this was a system that says what do you want, what are you looking for, give us an idea. You could go in, and based on saying I need something that is rainy, driving up the Pacific Coast Highway, sad, it would give you a list of here are 200 songs that fit that category, here are the ones that you can license right now on the platform without having to talk to anyone because we've precleared these, and the minimum is $500, or whatever the price was.

YouLicense has got [Mayor Ezer], who started the company, agreed – I got him to agree with Warner/Chappell to build this site. The day before it was going live, Scott Francis, who was running Warner/Chappell at the time calls me and says, "We can't launch it." I said why. He said, "The staff thinks it's the first step in eliminating their jobs." And I said it's not. It's freeing them up to have the $10,000, $50,000. They're not just dealing with the volumes of calls where they're going, "No, we can't do that. Bye."

But they pushed back really, really hard, and we didn't launch it. And fast-forward about a year and a half later, everyone that objected – and Judy was one – Judy Stakee was one of the people who objected, and a guy named Brad Rosenberger, they ended up leaving Warner/Chappell because Warner/Chappell didn't hit their numbers that year. And so what we thought would empower them to increase their revenue they looked at something that was marginalizing them.

You know, you now have – the other use cases – so I ended up – I worked with Mayor, and we did a few of those things. And ended up working with Musimap, which is out of Berlin and out of Belgium. The use case there is MTV Networks has, you know, 20 reality shows. Their music budget is really small, but they're looking for things that deliver a certain emotion or a certain lyric or whatever. You could put in the Musimap system I need a song like Adele's "Hello" that has the line in it, "I thought you loved me," and it would find you replacements that weren't Adele. It might not be a name artist at all. But the music hits the emotional target, it needs the hit. So a music supervisor for one of those shows could bring the music in on budget, and maybe save enough that for an opening theme he can get something or she can get something they really want.

LP: So is your sense in that use case, Ted, that there will be people and productions and budgets for which the superstar is always in order because they need it and want it and can't afford it. But there is this sort of – I hate to use the word, but there's this long tail, or there's this mid and low end of the market for which they just need the mood and the sentiment, and it's not about the superstar brand.

TC: Yeah, I mean, and you know, the name part is usually underscore. So do you need thematic underscore from a major composer, or do you want music in the style of John Williams without it being – without plagiarizing any major theme that John Williams ever created? You want that feel, but you can't hire John Williams to do your Netflix show. It's just not realistic.

So in some cases, I mean, you can have an Amper – Sam Estes is over there. You can call up Sam and say, you know, this is what we need, or go on the site and pick out what you want, where before you'd have to say let me find a B-level or C-level composer that was an understudy in John Williams' publishing company. But I met Sam Estes a year ago – actually, it was just before the pandemic. It seems like a year ago.

LP: Yeah.

TC: And I teased him. I said so what Amper does is it writes songs in the style of Hans Zimmer, like the songs that Hans Zimmer had somebody else write for him in the style of Hans Zimmer because Hans Zimmer has an Andy Warhol type of composer factory where he'll say take this theme here now and embellish it where basically it's under his supervision, but he may not write every note. And says, "Well, you know our company is financed by Hans Zimmer." I went, "Oh." Great moments in – and I really like all of the stuff that he says that he wrote.

You can do that. You can basically create by, again, training the engine, you know, here's what I'm looking for, and you input a bunch of stuff, and it outputs stuff. I had a call with a guy yesterday, part of this Hackathon and conference, Walifornia in Belgium. And the company's called Dadabots, D-A-D-A-B-O-T-S, dot com. [laughs] It has a channel on their website where it has been continuously outputting death metal. He basically said he put in every – and I can't even name all of them – but he put in bands that may – you know, like Rammstein, Rammstein, I never know which way it is. You know, really death metal, black metal bands. Put everything into the system, and it's outputting death metal.

And it's just instrumental, and it runs 24 hours a day. It's just a continuous – it's streaming the output of the system. And every once in a while something sort of sounds like something somebody did. And if somebody raises their hand and says, you know, that's really close to that two chord – I'm being facetious – really close to what we did, they'll take it out of the system because, again, monkeys with typewriters, at some point it's going to accidentally write Romeo & Juliet. So they will go in and make adjustments.

But I mean, it's fascinating that – and again, I mention Nico, his thing is I'm a composer. This is no different for him than a new native instrument synth or a synthesizer or a sequencer, or a new version of Albeton or Pro Tools. In every iteration here, people who didn't have access to Ableton or Pro Tools or whatever go, "I wrote, and I didn't need that. I didn't use a sequencer." Now you can.

LP: Yeah.

TC: So it becomes part of the toolset. So I don't think it's any less of an instrument or a accessory than, you know, a keyboard, a drum machine, different kinds of mics, different kinds of signal processing. It's just at the end of it has to sound good, and it has to achieve the emotional, and you know, the creative goals. But I don't think it's any less valuable than, you know, things that are being – have been done for years.

LP: Yeah, I think having the – making the qualitative argument about the tool itself is never – that's not really that interesting of a debate, right. There's always the back in the day, or when I had to do it, that's the least interesting part of the discussion.

I'm curious, what was Ted Cohen doing in 1977 that had him in a hotel room with Wozniak and Jobs. I take it you weren't delivering pizza.

TC: No. So this is how crazy this is. So I grew up in Cleveland, and in high school my mother was a party planner before that term existed. She somehow ended up there were a few wealthy families in Cleveland who started hiring my mother on a regular basis to do parties that got them in the Sunday style section of The Cleveland Plain Dealer. And it came time for my bar mitzvah, being a nice Jewish boy from Shaker Heights, Ohio. The party was "An evening at the Cohen cabana," not the Copa Cabana, "starring Ted Cohen and his first appearance as a man." And my mother ends up calling the local TV station where sometimes she would hire the newscaster or the weatherman or whatever to be the MC at a party. She said, "Who is there that could sign at my son's bar mitzvah?"

And I used to remember the guy's name, but I can't. He was the weatherman, and he said, "Well, we've got this new guy here, Mike Douglas." [laughs] The Mike Douglas Show. He said, "Let me ask him if he'd be interested. He just started doing the show two weeks ago. Woody Fraser, who had discovered Merv Griffin – not discovered Merv Griffin, but created the Merv Griffin show, had seen Mike in a piano bar in Chicago. And the story goes that Frank Sinatra sang with, you know, the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, and Mike Douglas sang with the Kay Kyser Orchestra. And Frank Sinatra became Frank Sinatra, and Mike ended up playing in piano bars.

So he's got the TV show – I don't want o burn too much time with this. And he's two weeks into it, and he calls my mother, and he says, "I'll do it for $50 if I can bring my wife." And so Mike Douglas came and sang at the bar mitzvah. I won't hold the picture up. It's hilarious. And it kind of defines what we're doing right at this very – you and I are doing at this very moment. He invited me up to say a few words to my relatives that were there at the party. There were about 200 people at the party.

And 20 minutes later, my mother is waving her arm going, "Sit down. You're done." So the picture says, "To Ted, god bless. You ad lib very well." Because I'd say, "Hey, grandpa, grandma, how's it going?"

His assistant was a woman named [Marianne Moyer], she married a guy named [Jim Gallant], Marianne Gallant. Calls my mother one day. Now, there's no voicemail. There's even no answering machines. This is like 1960, late '64, early '65. Says Mike says to call. We have a band on the show tomorrow. They're coming to Cleveland before they're going to New York. Ted may know them. They're called the Rolling Stones. If Ted wants to skip school, come on down, he'll be on the list.

So the first time I met Mick and Keith was backstage at the Mike Douglas Show, and the first words I ever heard from a Rolling Stone was Keith saying Mick Jagger, "Stop being a fucking asshole. Sign his album." So years later at EMI, I ended up working with Mick, and he goes, "Nice to meet you." And I said, "No, I met you when I was 14. You wouldn't sign my album."

So I manage bands all through high school. I go off to Ithaca College. I'm in premed. The week I get there, I find out Rod Serling's teaching. I go to hear him speak. I go to the head of the communications school at Ithaca, and I say, "Can I change my major? I'm going to break my mother's heart, but I'm not going to be a doctor." Came back – this all ties in. Came back to Cleveland, and – for summer break, and I ended up meeting a guy named Billy Bass. I don't know if you know Billy. Billy ran Chrysalis for a while. Got mentored all along the way, and I end up – Warner puts me in Boston doing artist development.

And my girlfriend at the time was the woman who had been Frank Zappa's secretary in L.A. Frank's manager calls me and said, "My secretary just flipped out. She hates L.A. She got in her car. She's driving to Boston. I told her to call you when you get there. Will you have dinner with her?" We ended living together for 10 years.

I'm reading the Sunday Boston Globe. See, now that took five minutes to get to, "What were you doing in a hotel room?" And there's an ad that says, "Chairman of Advent Corporation seeking executive assistant." I turned to my girlfriend, and I said, "You're going to work at Advent." And she said – she had been working at DBX. She had gotten a job at DBX when she got to Boston. And I said, "You're going to Advent." She said, "Why?" I said they've just come out with this new – the big-screen TV. It was called the Advent VideoBeam, and I said, "I want one, so you're going to go work there."

So she goes to work there, and it turns out the guy she goes to work for there is a guy named Peter Sprague. His father was National Semiconductor. I refer to him affectionately as a trust-fund kid. And he liked things, so he liked Aston Martin, so he bought Aston Martin. Not the car, the company. He liked Advent speakers, so he bought Advent. So she's now his assistant. I start meeting him and I said I've got – "The Doobie Brothers are going to be at Boston Gardens next week. Would you like to come?"

He turns to me one day and he says, "We're going to Chicago for this thing called the Consumer Electronics Show. I think you'd like it. Why don't you come along with us?" And so that was my first CES. We're the Drake Hotel on Michigan Avenue in his suite, and they've taken the furniture out of the bedroom, and they've turned that into my first experience of a home theater. Jobs and Wozniak showed up to trade an Apple 1 computer for an Advent VideoBeam. And because the Apple 1 was the first computer that natively output in color graphics.

So the trade was made. I had nothing to do with it because didn't work for Advent. Somebody at Advent ended up with an Apple 1, which is worth probably $200,000, and they ended up with an Advent VideoBeam, which I guess if you melted it down, would be worth about $50. I have no idea. [laughs] But I ended up talking to them, and they got me interested, like I said, in talking to Atari. So I became the liaison between Warner Music Group and Atari on where this is going to go.

Years later, I ended up reconnecting with Steve Wozniak. We ended up on the board of a company together called en2go because do you know who Captain Crunch is?

LP: Yeah, the notorious –

TC: – John Draper. –

LP: – phone manipulator.

TC: John Draper. So John Draper went to prison for Steven Woz. He took the rap when AT&T had the FBI raid Apple because Apple before it was a computer company was actually building boxes that cheated long distance. You'd go into – it was a blue box. John Draper is the engineer at this company en2go in 2007. And he asked Steve to join the board, and next thing I know I'm on a board with Steve. It was very cool. He's a great guy.

Jobs on the other hand, not speaking ill of whatever, was not as nice as Woz. We'll just leave it at that.

LP: Yeah, I don't think we'd be the first person to go on the record saying that. Is –

TC: – I'm sorry?

LP: Is Draper still alive?

TC: He's still alive. He had a really bad health scare for a while. He was in the hospital. He was actually in intensive care. There was a – I think it was a Kickstarter campaign, or it might have been an Indiegogo. He was selling re-creations of the blue box. They don't do anything anymore, but he was selling based on the original ones that he had, he had some made, and you got his book, The Blue Box or whatever for like $100. So a bunch of us bought one. Very nice guy. Completely still crazy, but a really very nice guy.

LP: Was he successful in – did he end up having a tech or entrepreneurial career, or was he sort of a fringe figure? How would you describe him?

TC: Again, I talk about my life ends up being a series of serendipity and [Zelig] moments. So and again I'm jumping all over the place. In '72 when I was a local guy in Cincinnati – before I went to Boston for artist development, I was local for Warner in Cincinnati. And Todd Rundgren comes out with the Something/Anything album. And I'm listening to it and the single was "I Saw the Light," was the first single from the album. But I'm listening to it, and I hear this song, "Hello, It's Me," and I fall in love with it.

And I start calling a guy named [Paul Fishkin] at Bare Soul Records in New York saying, "Paul, you don't know me, but I'm the local guy. This is a hit." He says, "I think it is, you think it is, but nobody at Warner thinks it's a hit. Todd doesn't think it's a hit." I said can you press up 1,000 singles for me. Let me just try this.

So they pressed up 1,000 singles. I put some in some stores in Columbus and Dayton and Cincinnati. A year later the record was a top five record. Todd and I became friends. He came to Cincinnati and did a concert for WKRQ, which was the prototype for WKRP in Cincinnati, the TV show. And then Todd's manager gave me a concert. I said, "I can't. I work for Warner. I can't do a concert." But I think the statute of limitations is expired.

So I had a friend front it for me. Concert sold out. And I ended up – Todd started talking to me about video. So I got my fist video machine in '74. I got a three-quarter-inch machine. And I started looking at what music video was going to be. Paul and I stayed friends. Todd and I stayed friends. In '93 – wait, '93 or '94, I signed Todd at Philips for his New World Order CD-ROM, which was an interactive music – it never played the same way twice. It had what I referred to as a digital Legos that could reconfigure themselves and still sound like music. You know, it wasn't disparate. They had to – it was almost like dominos. They had to match. They go together, but they were different dominos.

So I stayed friends with Paul. I stayed friends with Todd. Paul worked with a guy named Tolga Katas, and Tolga was a dance music producer in the '80s. When I started doing what I'm doing, Paul called me and said we've started this company called en2go. I want you to meet Tolga. And it was a new video compression technology that was better than anything that was out there at the time. Tolga was friends with Draper. Draper was still friends with Woz. So I end up at a company where I'm there now with Paul Fishkin, who I've known since '72, "Hi, my name's Ted. I'm in Cincinnati." And Tolga, who had I become really good friends with. And Steve Wozniak, and the infamous John Draper.

And it was amazing. I mean, it was relationships. And I keep stressing this. You know, if you meet people that you like, be good to them. You know, try not to do anything wrong. If you do something wrong, apologize as quickly as you can. You know, I always joke Jewish guilt goes a long way. I have had a career, and anybody listening to this who has heard me talk before will hear me say, "Oh, he's saying the same story." But I had a guy – I was in – and again, I have this very visual memory of where I was. I say it's an episodic memory, and someone says it's visual cortex.

But I was in Las Vegas in the Bellagio Café in the Bellagio Hotel, and the phone rings January of 2001. And he says, "Hi, my name is – it's Scott Young. Do you remember me?" I said, "Yeah, you were Clark Duval's secretary at Capitol Records." And he goes, "Yeah, and you're the only guy who used to talk to me about what I wanted to do when I wasn't Clark's secretary anymore." I said, "Really?" He said, "You're the only person who used to listen to me and give me suggestions."

I said, "What are you doing now?" He said, "I'm global head of digital at Best Buy." I said, "Cool. Why are you calling?" He says, "What can I do for you?" And I said, "What do you mean?" And he says, "I want to do something. What are you working on that I can – that you can use Best Buy to realize?"

I had gone to – I had met the folks at SanDisk a few months earlier, and I had this idea about putting – making a catalog available. So basically the Rolling Stones entire catalog was a SanDisk micro-SD chip. You bought "A Bigger Bang," the new album, but if you had – and there were only four or five phones that would do it. But if at 2:00 in the morning you wanted to unlock "Sticky Fingers" or unlock "Exile on Main Street," you could punch up a few codes on your phone, and all of the sudden now you had access to the entire Stones catalog.

There was a guy named Rick – I'll think of his last name – oh, Rick Dobbis, who was Clive's right hand at Arista. Rick had tried to get me to go to Arista when I was at Warner doing artist development, but we stayed friends. There was a moment when I had to put this all together, and it was literally calling people that I had always had a good relationship with. We were able, in four days, to get Mick, Virgin, SanDisk, and get – and I had a friend who worked at ABKCO. What's her name? I think Iris Keitel, Harvey Keitel's sister. I called Iris. I said here's the thing, I want the whole catalog, so I'd like the ABKCO catalog too.

So we had the entire Stone's catalog on a micro-SD chip, and it was the first time that everybody had played nice in the sandbox. We started the discussion on a Thursday, and on Monday afternoon we announced it in a press release, and had an event at CES I think about two weeks later. And so I mean, you end up with this network – the technology is great, but you end up with a network of people that, you know, when they call you, you help them if you can. When you call them, they help you if they can. And it makes things go a lot easier.

There's a couple – I mean, I could give you a couple more examples, but I mean, it's – did you know Gerry Kirby?

LP: No.

TC: Gerry was the cofounder of Liquid Audio.

LP: Yeah, I remember. I didn't know Gerry, but I was around then.

TC: With [Phil Weiser].

LP: Yeah.

TC: And you know, I have a reputation for talking a lot, which I'm enhancing right now, but I also have a reputation that if I called you and said there's somebody I really want you to meet because I think you're going to really enjoy meeting them, you know I'm doing – you hopefully will know, as we know each other, that I'm not calling you because – to say can you get a hold of [Lawrence], or – you know, I would say to them possibly, no, he won't be interested in this, or you're not ready, or the application isn't baked.

So Gerry calls me one day on a Tuesday around 4:00. And he – how are we doing timewise? We're OK?

LP: Yeah, we're doing great.

TC: I'm sorry. [laughs] Gerry calls me around 4:00 on a Tuesday and says, "I'm flying on the red eye from San Francisco to New York. I'm going to be there Wednesday, Thursday, Friday. I need you to setup a meeting with Fred Ehrlich at Sony Music, who was running digital at the time. Five minutes later I called him back and I said, "You've got a meeting" – and he said, "I'm getting in at 7:00 a.m., so I can be there anytime after 9:30." So I said, "You have a meeting tomorrow morning at 10:00. It's Fred Ehrlich, Al Smith, David Waldman, Mark Ghanime, Mark Eisenberg." It was basically the entirely digital team at Sony.

And he goes, "Well, that seemed really easy. Maybe I should have done that myself. What am I paying you for?" And I went, "Oh, Gerry, I promise you. Ask me to do something else, I'll give you written reports, I'll give you updates, it may take me two or three weeks if you feel that's more valuable use of what you think you're paying me." He goes, "No, no, no. This is good. I just" – he just said, "That was really quick."

Now, that was good. I was on the phone with a guy – do you remember a guy named Michael Gallelli?

LP: No.

TC: He was running digital at – he was running music at T-Mobile in the mid-2000s.

LP: Oh, yes.

TC: It was him and Kyle Levine.

LP: Yeah.

TC: Great guys.

LP: They worked on – T-Mobile worked on – it was in the UK though. They worked on a Stones project that I was part of around that time.

TC: Yeah, they're both at Microsoft right now, and they're really great people. We were doing the ringtone deal directly with T-Mobile. We had already done a deal with Moviso with Mark Levy and earlier with Ralph Simon. And I had gotten them from a 60 cent wholesale on a ringtone to – up to 95 cents. We kept going back and forth. I said, OK, 95 cents. We're good.

I take it to a guy named Colin Finkelstein, who I hope watches this, and I said, OK, we've got T-Mobile done. It's 95 cents. He goes, "I think there's $1 there." I said, "Colin, I just told him we're done." And he says, "Well, go back to them and tell them you're not done. It's $1."

So I call Michael up, and I explain to him Colin wants it to be $1. He goes – and I said it's 5 cents. What's the – and he goes, "If I agree to the $1, are we done?" I said, "I give you my word, we're done." Where I fucked up, I called Colin one minute later, and I said, "Fine, you've got your buck." And he goes, "Well, that seemed easy. I think there's $1.25 there." I said, "Not from me." I said here's his number if you want to call him, but I've already told him that if you ask for any more, he should go directly to Moviso because Moviso was getting at the time for 85 cents, and even with their markup, it would be less than $1.

We never ended up doing the deal with T-Mobile. I called Michael back, and I said, "Call Mark. This isn't going to happen. They're playing games here. I don't have time for it." So I reconnected with them the other day. I sent them a note on LinkedIn that said, "Can we go to $1.25?" And this is like 15 years later. And he's like – he writes back, he goes, "Call me tomorrow." So we talked for about an hour. [laughs] He's having – you know, I mean, I've always tried to protect the people on the other side of the table.

I mean, I'll tell you one other thing. This is a weird one because it came out yesterday, and I hadn't thought about it in a long time. When I was on The Who Tour in '82, Bill Curbishly, their manager, says to me one day – he just turns to me and he goes, "You know, you're going to have a really sad life." And I said, "Thank you. Why?" He says, "You're too egalitarian." I said, "What do you mean?" He says, "You want everybody, on all sides of the table, to be happy with whatever the deal is, whatever." And I said, "Yeah, because at the time I was fighting with them over" – you know, the concept used to be – where were you in your teenage years?

LP: Where was I?

TC: Yeah.

LP: I was in New Haven, Connecticut.

TC: OK. So there was AVZ and NHC.

LP: Yeah.

TC: OK. So ideally, somebody at AVZ would call and say, "We want to promote the Van Halen show," and NHC would get blanked. What I tried to do on The Who Tour was AVZ would get the backstage visit the night of the show, NHC would get to send a winner to the show in Boston two days earlier. The – whatever station was in the market that should get a piece of it, got something that was unique. And in every city I'm going – because he was getting calls going, "No, we want the show as an exclusive," and I'm going no, if you want to sell the maximum amount of tickets, you want NEW, you want PLJ, you want the oldies station, you want everybody involved. So I'm trying to parse it out.

And he goes, "You worry about this too much." I have never changed. I mean, I am always trying to figure out how do I make sure that you don't feel that you got screwed in the deal, that you're bent over the – literally that you weren't coerced into making a deal you don't want to make. So when I ended up – and again, we're not in any – I love interacting with you because it goes all over the place. You know, I go to – the date was like May 5th or 6th of 2000. I had been hired by Jay Samit to put on a private EMI digital conference. I had just done Web Noise, the November before we did Web Noise '99, and it was like –

LP: – Web Noise.

TC: Were you there?

LP: Yeah, probably. Yeah.

TC: It was like Woodstock. It was at The Century Plaza in L.A., and it was amazing. And Jay said, "Could you do a private conference for EMI?" I said yeah. And he said, "Could you fund it? Could you get it funded?" I said easily. And he goes, "OK. What's the pitch?" I said you've just hired 30 digital people around the world, Microsoft you can go to 30 different cities over the next two or three months, and meet each individual person, and you know, do the pitch, or you can come to Atlanta the weekend of May 5th, and you can meet everybody. We're going to hang out. We're going to go to movies. We're going to have a show. And by the way, you're buying dinners for – it's $50,000."

So I was able to raise $300,000, excuse me, for a private get-together, and it turned out really good. But when I got there – and I have to tell you the other part of it. I decided I wanted to see what the subway was like in Atlanta, so I took MARTA from the airport to Buckhead to go to the Ritz Carlton. And I get off the subway, and I come upstairs, and there's a cab outside. And I said, "I need to go to the Ritz Carlton." And he laughs, he goes, "OK, get in." And he did a U-turn around the street, and said, "OK. Here it is." It was across the street. I didn't see it.

So I end up –

LP: – I did that the first time I went to New York to get to the Roosevelt Hotel. I got out of Grand Central Station, got a taxicab, said, "Take me to the Roosevelt." He drove around the corner. [laughs]

TC: Exactly. I love those moments. So I go into the bar at the Ritz Carlton, and Jay's sitting there with a guy named Frasier Hollis. Frasier ran amplified.com. And he goes, "Ted, why didn't you tell me?" And I said, "Tell you what?" And he hands me the program for the conference. And I'm looking at it, and I went, oh. I said, "You know, I should have mentioned to you. It happened very quickly. I guess I should have briefed you." Frasier leaves, and I turn to Jay, and it said, "What the fuck?" In the program, it said, "Jay Samit, senior vice president, new media, EMI. Ted Cohen, vice president, new media, EMI."

I said this isn't going to work. He says – he said, "What do you mean?" I said, "I told you a year ago you can't afford me." I said I've got 25 clients that are paying me reasonable retainers, and I'm making, you know – I'm doing much better than I could do if I came to work for you. I won't go into the numbers, but the numbers were stupid at the time. It was the first digital – I had – I was representing everyone. I joked that I wanted to be the Alan Grubman of digital being that I represented everybody in the room, and nobody had a problem with it.

And I did. And every – and again, Gerry Kirby would call me and say, "So just between you and me, what's RioPort up to?" And I said, "That's funny. They asked me yesterday what you were up to, and I told them that I couldn't tell them. But if – I'll tell you what they're up to, if I can then call them and tell them what you're up to." "No, never mind. I just thought I'd ask."

So I'm sitting there with Jay. And he said, "No, I've got it all worked out. You're allowed to keep your clients." I said what do you mean? And he says you're going to head up digital business development, but you can keep your consulting process. Just have Jill – there was a woman, Jill Johnson, I don't know if you met Jill over the years. She's wonderful. She took over running the company, and I had no active role in it anymore, but I had residual income. And he says the one thing is you can't negotiate with your clients for EMI. You can't be on both sides of the table.

That lasted for about a month. And about a month into it I showed him that I could get the deals done quicker. My clients were getting less of a deal than they were trying to get, but they were actually getting the deal that they would have ended up with anyway after going back and forth. And it was a much more efficient process, and I made sure I was being true to what EMI wanted to do, and I was being true to the client. And people were saying to me you can't do both sides of the table and satisfy everybody. And I said you can, and there's a way to do it, you know. You have to be transparent with everyone.

So I said look, I know you wanted to pay this, but you're going to get that. So I get brought in sometimes by clients when they're stuck on a negotiation to basically say to the person across the table, "Look, you and I work together. You know you're overreaching. Come on. You know, if you're going to" – there was one company, I can't tell you exactly who it was, but there was a company that wanted to change one of the client's deals from 50/50, where in business for four years, to 90/10. And I said you're not being greedy enough. Let's just go for 100 percent. When the checks come in, we'll just endorse them to you. Why stop at 90? If you're going to take 90 percent, take 100.

And they were like, "What do you mean?" And I said can you really sleep at night saying you want to change it to 60/40, whatever the reasoning is? I can understand you while you're saying we're four years into it, it should be a more equitable split, we should get a bigger share, 90/10. We ended up in a really good place, but I had to sort of go we actually don't need you – you're not as important to us as you were, and so if you want to try and do it on your own, we'll take a year off. And so if you want to try and do it on your own, we'll take a year off, and then come back to us in a year and see.

We were providing a service, and if I keep talking, you may figure out who it is, so I'm not going to do it. But there was the ability to say we can walk away from this. And we ended up at a – we ended up with the client paying more than the 60/40, but not much more. But for that, they got better treatment. There were other things that I said if you do this and this, and they were sitting there and I'd say, "They'll agree to it."

We get it all done, and one of the partners turned to the room and said, "Can we just" – and we both turned to him in unison accidentally and went, "Shut up. We're done." So and I kept saying to the client if you don't like what I'm saying – if either of the parties in the room, if you want me to leave, tell me when you want me to leave, but from my perspective, this is what you need to do. So I mean, I've worked really hard to move things forward.

And I'm also very good at calling someone up saying, "That call we were on just now, you were really an asshole, and you can't do that again." "Well, why do you care what I said to them?" I said, "Because it just isn't – you don't grind people like that." I happened to have one of those calls this morning, so I just called somebody up, and I went, "Don't do that again?" And they went, "What do you mean?" And then they actually wrote me in an internal thread on Slack, a public, "Hey, I'm glad we worked everything out this morning." And it's like we're fine. So I mean, and again, we're at –

LP: – Let me ask you this, Ted.

TC: OK. Go ahead.

LP: You told me this a few minutes ago that – you referenced, "When I started to do what it is I do," in regards to sort of your business.

TC: Right.

LP: How – what do you do? How do you describe what you do? Because I have a notion, but I'd love to hear you articulate it.

TC: I – because – I believe that because of the way that I approach it, I'm not an attorney, but I explained it to somebody who was asking, "Why do we want to work with you, and what are your skill sets?" And I went, "Well, you called me. Your boss wants to hire me. And now he wants me to sell you on why he's hiring me, but here, I'll go through it." And I made a list of this is what I think I'm good at. I said, "I'm not an expert on any of those things, but I have a really good appreciation for each of those issues, whether it's legal, whether it's, you know, distribution pipeline issues. I have enough knowledge about the various facets that I can make an informed suggestion of how we approach the negotiation and solve it."

So I said I'm an enlightened generalist, and I – you know, when I was at Philips, I was doing the Cranberries disk. I'm trying to do this one really fast. I was producing a title, a CD-ROM for the Cranberries. My idea – because CDI was – if anybody remembers what CDI was, it was a failed platform from Philips that they spent $1 billion trying to launch. I wanted a single SKU, a single disk that played in a PC, played in a Mac, played in a CDI player, played the audio tracks in your audio player. Played the video files on either an MPEG video card. Basically, it would play on anything.

And they said, "Well, I don't know if that can be done." They said, "Go talk to engineering." I went down. Was hanging out with the engineers, I said, "This is what I need. How quickly can you do it? And how much will it cost?" And they said, "It will take six months and half a million dollars." I said, "You've got three months, and I've got $200,000 left in the budget. " And they went, "Yeah, we can do it." And we delivered a disk. It was called – if you know, like CDs are red book audio.

LP: Yeah.

TC: And video is white book audio, and photo CD is yellow book. There were literally these binders that were colored binders that had these standards. We called it a rainbow disk because it played green book, red book, white book, yellow book, and blue book was a CD. Philips and Holland went nuts on me because I was breaking – I was violating every standard, every one of those. We had basically created, you know, nachos in terms of all the different things that were in there.

LP: Franken-disk.

TC: But we were able to get it out. I was able to get it into retail. I was able to talk to the folks at Tower Records about carrying it at Tower, and talk to the people at Cybersmith, and – which were Micro – at the time, Micro Pro or Micro Computer. I was getting computer stores to carry it. And we had two different – we had the same disk, but one was in a software box, and one was in a CD. The CD was just in the jewel box without the packaging. We sold a quarter of a million of them at $29. And it was very successful because I believe that I'm able to talk to everybody in the various, you know, participants, the people that are involved and get everybody to play nice in the sandbox.

So what I do now is when I'm working with people is what are your objectives, what are you trying to do, and let me see what I can do – do you want to keep going, or do you want to stop?

LP: No, by all means.

TC: OK. You can cut whatever you want to cut. My thing is I give you – my running joke is when someone says, "What do you cost?" And I said, "I cost X to do for you what needs to be done, and tell you what you need to know. And I cost XX to agree with everything you say and only do what you tell me to do." You know, because I think my value to you is that – is you know my input. If you're not going to listen to me, and you're not going to take any input, and you're going to just go off and do whatever you want to do, I actually don't want to take the money from you because now my name's attached to it. And when it goes south, it was, "Well, I heard your client went under," yeah, but he never listened to me. So I don't want to be in that position.

I had a client that I resigned from because he would call me going, "I just made a deal with Sony Publishing. What do you think?" I think you made a deal with Sony Publishing. If you – hang on a second. We've got to – the Roomba goes off on the hour. One second. [laughs] OK. I'm back. Sorry.

LP: You're surrounded by technology that's thinking for itself.

TC: Right. The guy would call me every few days saying, "I just did such and such. What do you think?" I said you – I can't work with you anymore because if you want me to be a cheering section and congratulate you, first of all, yay, but I'm not really – if you had sent me the publishing deal two days ago to skim through it and just give you not a legal opinion but an operation of what does that agreement mean, and how can they screw you in that agreement, then I'm of value to you." You're familiar with Muze? So I'm consulting for Muze in – around 2011 or '12, and this guy there named[Lonnie Chenkin. And Muze at the time was owned by Alliance out of Florida. Alliance Distribution.

LP: Long after – who was in it, Trev Huxley?

TC: Well, Trev had left Muze, Paul Zullo had left Muze. This wealthy guy bought it, along with the guy who owned Alliance. They were partners on it. But Scott Lehr was still there and Gary Geller, who – again, I ended up working with Gary Geller. Gary Geller was our roadie on our Sex Pistols tour. Now he's business development at Muze at that point.

So Lonnie calls me one day, and I might as well just tell you the whole thing, and you can edit it down. Lonnie calls one day, and he goes, "I've got ask you a question, some questions." He goes, "Are we a client?" Yes. "Do we pay you?" Yes. "Do we pay you on time?" Yes. "Do you like us?" Yes. "Do you like us?" Yes. "Do we pay you enough?" No, but that's another question. We'll do with that another time. He says, "OK. I have to ask you, I got a call just now, and I'm kind of upset. Did you recommend Rovi to somebody yesterday?" I said yeah. "But we pay you."

I said yes, but somebody called me, and said who is the best at a certain thing. Rovi is better at it, as I always go, mirror, mirror on the wall, you're not the fairest of them all. And he goes, "But we pay you." And I said not to say to say the best if you're not. I said my value to you is people know when I tell them something that it's either true, or that I totally believe it's true. I'm not reading from a script of these are the most wonderful people, and they have – I said, so when we go into Sony next week to meet with Fred Ehrlich, when I say to Fred Muze is the best for what you need them for, for – I forget what it was for that we were going to do at Sony, Fred knows that, yes, I'm getting paid by you, but I wouldn't sit there and say Fred you need to do this because it's great for Sony.

And a lot of times I'll say to clients you always have to think about Universal knows why you want the deal with them. Sony knows why you want the deal with them. Why do they want the deal with you? Yes, there's an advance, but what's it doing to enhance Sony's website, enhance Sony's, you know, how their artists get exposed. What is the underlying value of the technology that is going to make it easier for Syd Schwartz at Sony Legacy to promote the Journey catalog. So really think about not, "Hi, we really want to deal with you," but, "Here's why you want to work with us." We're giving, you know, in-depth exposure to the legacy artists. We're doing whatever the application or the service is.

And sometimes people have trouble with that. I mean, I don't care at this point. I worked with Quboz. It's a French – it's sort of like [Desserts]. They're Paris based, high-res, you know, 24-bit, 192. The gentleman who owns the company is a serial entrepreneur. His name's Denis Thébaud. Really smart man. I really enjoyed working with him, but I discovered that he was – I can't think of another way to put it. He was very Trumpian in that he would pose a question like, "Wouldn't you agree that such and such is whatever?" And I'd say, no, actually, I think it's this. But of course it's obvious that – no, Denis. Here it isn't. He stopped asking me things because he wasn't asking me what do you think about this, it was don't you agree with me.

LP: Yeah.

TC: And when I didn't agree all the time, we drifted. And so I worked for him for a year, and it was – and I really enjoyed it, and I enjoyed – the product is great. He's a wonderful guy. It – he's the CEO, chairman, owner of the company. And he wanted me to get the deals done, which I think I did a pretty good job, but he also wanted me – you know, he'd ask me aesthetic questions about, well, don't you think whatever, and actually I think it's more like this. You know, other clients are very open to that kind of input.

I've been – I've, you know, had clients that we have really had just go at us. I've been brought in to do day-long, rip it apart, and I always go it's insightful but not spiteful. I don't try and be a jerk about it, but I'm going here is where you're missing it, in my opinion. In my opinion, not in the world, but here's where I think the disconnect is. So it's been a lot of that.

It's getting them – it's getting people in front of people – for example, if you're doing a deal with Universal, there's a great guy over there, Tuhin Roy, who I worked with years ago when he had a startup. I can, let's say allegedly call Tuhin up and say I've got a client you have to see. They're not funded yet. They don't have any money for an advance, but I want you to see this first because it's amazing. And normally it's who is the attorney, or how much is their potential advance, or who are they funded by, and I'm able to jump that line because I don't want anyone to ever turn to me and go, "You just stole an hour of my life that I'll never get back. You owe me. That was horrible."

I really – it's almost like prequalifying somebody for a mortgage. I mean, I won't bring someone in until I think coming in to see you that you're going to go, "Ted, that was great. And I love these guys, and let's do something." As opposed to, OK, you got them the meeting they wanted, you owe me dinner sometime.

LP: Yeah. It's – you're trading in value add as opposed to trading in constant favors.

TC: Yeah. You know, and so most people literally, I mean, I will write to Mark Cuban is not a good example. But there are people, Chris Fralic, First Round Capital. I don't know if you know Chris. Chris was – they funded Ring. They funded – First Round is an amazing company. If I write, "I need 10 minutes," he doesn't say, "Send me the deck, what's it about?" He goes, "I'm good tomorrow afternoon 4:00, but I only have 10 minutes," and I write back, "No Van Halen stories." And I do 10 minutes. And you know, I had one of those – I was on – there's a wonderful guy who you may know, [Jeff Cockrell].

LP: Yeah.

TC: So he was at Converse. He built those recording studios whereas – whatever, and then he went to Coca-Cola.

LP: Didn't they have a flagship one in Brooklyn, was it?

TC: They had one in Brooklyn and one in Boston. And that was his idea, Converse, just an amazing guy. Then he went back to Coca-Cola where he had started. And – I need a sip. I'm sorry. An old friend of mine is starting – has started a company – might as well do this, and then you can cut this out whenever you want to cut it out.

In 2004, a company approached me at EMI to do a test on a product that's called PhatNoise. And what it did was – what kind of car do you have?

LP: I have a 1992 Volvo 240 GL in mint condition.

TC: Did you have a six-disc changer in the back?

LP: No, but I've had a car with a multidisc changer.

TC: OK. So this was the coolest thing ever. You basically opened your trunk, you unscrewed your six-disc player from its mount. You screwed in the PhatNoise unit, you plugged the cable back in because it had an adaptor cable that matched your cable in your BMW. And now you had a 100-gig removable cartridge that had a dock also in your house. So you take the cartridge out, bring it in the house, rip your CDs, put it in the cartridge, you now had 5,000 albums in the trunk of your car.

LP: Yeah.

TC: But the head unit on your radio still thought it was talking to a six-disc change. There as no new software. You now though when you started scrolling, instead of scrolling through Disc 1 through 6, you're scrolling through Discs 1 through 5,000. And the only thing they added was they added voice synthesis to say "Robby Williams, Neil Young," so you could turn it while you were driving, and you'd go, oh, there's Neil Young. I'll do it.

Anyway, they sold the company to Harman Kardon. There were two cofounders, [Susan Paley] and Sharon Graves. They sold it to Harman Kardon. Susan went to Harman Kardon. Sharon went to DTS. I ended up working for Sharon at DTS. They have their version of mesh networks, similar to [Sonus]. And they were having trouble with Spotify and Title and Amazon making their interoperable mesh network compatible with the music services. So she hired me to go to the services and call people like Drew Denbo at Rhapsody in devices and then was at Amazon as they were – please don't – I get scared every time I say the A word. Something goes off here.

LP: OK.

TC: I called Drew up and I said, you know, here's why this needs to happen, here's who these people are. I lost track of Susan. I thought – I assumed she was still at Harman Kardon. I reconnected with her three months ago, and she says, "I'm on vacation right now. Let's talk in a couple months." And so I called her about two months ago, and I said, "So what are you up to?" She has this company if – I don't know if you have a second computer in front of you, but she has a company called droplabs.com, D-R-O-P-L-A-B-S. So I said what are you doing. And she said we're making these sneakers.

So as he reaches down, these are the sneakers. But you will notice they light up. They are stereo subwoofers in the shoes.

LP: Get out of here.

TC: They're amazing. They're just fucking amazing. They – what happens is you sync the shoes to your iPhone or your Samsung. The shoes then send – and then you – the shoes then sync to Spotify. And then the shoes send the rest of the information. So the link is from your phone to the shoes, you log on to Spotify. The shoes are sending the rest of your information to your earbuds. And you know, I'm talking a little bit out of school, but I think Jeff could be a greater advisor to her, so I introduced them. And they hit it off, and they love each other, and we'll see what happens with it.

So she sent me a pair that I did a review on for the newsletter for MediaTech Ventures that I work with now. And but the funny part, for anyone who knows me, I said, "So you've been at Harman all of these years?" And she said, "No, no, I left Harman in 2009." I said where'd you go, and she says, "Oh, I was the first hire. I was the president of Beats for six years." She's working for Jimmy and Dre, and I must have done an audible gasp, and she goes, "Why, don't you like them" And I said, no, I loved them, I was just thinking about all of the headphones I missed over six years.

She's like, yeah, I always wondered why you didn't call. I said I didn't know where you worked. And she's telling me all of my friends who were calling who I had introduced to her who knew she was there. Anyway, the guy who invented the shoes brought them into Beats around 2014 or something. Jimmy and Dre passed on them. When she left and took a couple years off, she then called the guy and said what did you ever do with that shoe idea. They partnered, and she finally brought the shoes. They officially ship August 1st. And so on a – she may never be a client, but she's a friend, and she's always been good to me.

So you know, Arabian Prince?

LP: Yeah, of course.

TC: So Arabian and I have become – I'd say not best friends, but – I always like to overstate it, but we get along really, really well. And so I introduced Arabian yesterday to Susan for – he's more of the demographic that can talk about how cool the sneakers are, as opposed to an over 50, we'll leave it at that, heavyset guy from Shaker Heights. So Arabian is going to talk to her later today about being an evangelist for the shoe company.

LP: Yeah. So that's what you do.

TC: So I like connecting people. And in a lot of cases, it's you know, someone will say can you do an introductory email, and I'll do an email that says, "Lawrence meet Arabian. You have much to talk about." And that's all it will say. It won't say – and both sides know that if I introduce you to Arabian that what he wants to talk to you about or what you want to talk to him about is going to be of interest to the other party. And you know, let me know if anything comes out of it, or let me know if someone's not answering. If someone's answering the talk to each other, then I smack the other side that didn't answer the email.

And I'll say to companies in some cases you may never hire me, but I like what you're doing, and you know, here's what I – it's not always altruistic. I like getting hired. But at the same time, I like seeing companies – you know, I like seeing companies grow. So you know, I will do a lot of stuff. I don't know how else to explain this. You know, I like working with really clever people and smart people and nice people, and I like menshes, and I don't tolerate mooks very much.

And so I tell – you know Toby Momis?

LP: Mm-hmm.

TC: So Toby and I have been friends since when he first started working for Alice. And I met Shep in 1971 in Cincinnati at the Carousel Inn on – I forget what the name of it – it was by the Cincinnati Gardens. And he ruined the rest of my life because Shep Gordon is one of the smartest people I've ever met, he's one of the most honest people I've ever met, and he's one of the most pleasant people. And I started judging every manager afterwards based on Shep Gordon, and it's a really high bar.

LP: Yeah.

TC: I've met smart managers that are assholes. I've met lovely people that can't get out of their own hotel room. I mean, Shep was like the real deal, but he taught me a lot. If I'm leaving words of wisdom for whatever, I worked for Sandy Gallin in the mid '80s. If you called me when I was at Warner, I would call you back at the end of the day. If I missed you, I would leave a message with your – you know, your answering service or on your machine. There still was no voicemail, '84. I go to work for Sandy, and Sandy says, "Did you get a hold of Lawrence?" And I go, "Yeah, I left him a message."

"I didn't ask you if you left him a message, you stupid" – much things. [laughs] Did you get a hold of him? Did he sign the deal? Did you get the check good? Is the check in the account? Did the check clear? Did you get the deal to the attorney, so they know it's done? Otherwise, you didn't do shit, get the fuck out of my office. And I learned the difference between you called me, I called you back, so you couldn't say, "Hey, you never returned my" – I mean, if you answered the phone, I wanted to talk to you, but if I didn't reach you, tag, you're it. You know, I returned your call. Sandy taught me about get it done, and whatever you have to do to get it done, get it done. Just be relentless.

You know, I tried to smooth that out, so I wasn't doing it Sandy style. But it was an interesting life lesson in how to get things done.

LP: Yeah. Well, thank you for being so generous with your time and your story. I really appreciate it.

TC: Did I answer – do you have other questions? I'll do, you know, I'll do one-sentence answers. I don't want to – I feel bad. Do you know Dan Steinberg? Steiny?

LP: I do. Yeah.

TC: So two years ago, almost three years ago now at South By, he interviewed me. He was doing a bunch of interviews at the Driscoll in his room. It's two months. It's six months. And I finally called him. I said when are you airing my Promoter 101 podcast? And he said, "Ted, I asked you one question, and an hour later I said thanks." And he said, "I don't know what to do with it." And I said I've had this problem before. Just intercut it with the questions. [laughs] Because I answered everything you wanted me to talk about, I just did it, you know, as verbal diarrhea.

And so he did that, and he added the questions and whatever, and he ran it. And I listened to it, and it was OK. But it starts out with where do you think this is going and whatever, and I went through and here are the promoter issues, and this is what happens when the show – but I can equally – again, cut all of this out or whatever. I'd been working – I worked with Prince for the first four years. And I became friends with everybody in the band. And actually I became friends with Prince. He came over to my – at the end of the Dirty Mind tour he came over to my house two nights in a row to hang out and watch music videos and not say a single word. I mean, he just sat there and said, "Show me music videos." MTV was coming out a few months later.

Dez and I though – Dez Dickerson, who was the lead guitar player along with Andre Simon, we've stayed friends continuously. We're working now on doing – he's been working on doing a documentary about Prince from high school up to Purple Rain because he played with Prince in high school. He was in the bands – they went to high school together.

So these friendships, and the – if they're good people, we stay in touch. And the people that I'm calling now, and I won't get into where we're at with it, there's somebody who asked me something one time, and there was no upside for me doing what they asked other than it was a nice thing to do. And so when I called them and said I want you to hear what Dez is up to, things moving forward, and we may have found the executive – we may have found the main people to put on the project, you know. Hypothetically, Quincy Jones presents, or whatever that branding is. But it comes out of I got a cold call from this guy five years ago asking me could you help me with such and such, and I said yeah, sure, because I knew who he was.

So I always say to people just, you know, until you find you can't be, be as nice to everybody as you possibly can be. Be as, you know, collaborative as you can be. And if I say I'm going to call you back on Tuesday, and I don't call you back until Thursday, I'm writing you notes going, "I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry." It's not like, "Well, I was busy." It was like, "You have no idea how many times I went to pick up the phone to call you, and then something else happened." So that's how I approach it.

My girlfriend Maggie is like, "Why do you spend all of this time talking to some people?" And every once in a while I'll show her an email back saying, "I met you in the lobby of whatever a year ago, and you introduced me to so and so, and now we got funded, and we'd like to talk to you and whatever." And I go even if that never happened, you know, it was somebody that I wanted to help that I believed in.

I can send you the image. You'll get a kick out of it. In 2000, the Jewish – what's it called? Jewish Welfare or whatever. The Jewish Federation of L.A. had us do a "Let's kibbutz about digital." And so I had Christina Caleo from Microsoft. I had David from – oh, gosh, from Universal, the attorney David Ring. I had Richard Wolpert, who had been working with Yucaipa and with Ovitz. It was the all-star list.

And then there was a kid on the panel, and everybody's going, "Why's he on the panel?" And I said, he's obnoxious as hell. He's a pain in the ass. But he's one of the smartest people I ever met. And he'll say that, "I remember when we had the kid on the panel." Somehow when I say to people, "Yeah, I had Travis do this panel back in 2000," and I think Travis – you'll either like this or you won't like it. Come on, you can do this. Do you know who I'm talking about? Travis Kalanick's current net worth.

LP: Oh. [laugh]

TC: So literally when I called – I've had a couple of times I've had to call Travis in the last five years. When I call him, he calls me back. When I write him, he writes me back because when nobody liked him, and he was running Scour – I mean, my mousepad here – my Scour Exchange mousepad, then he went to do Red Swoosh and whatever. But when I met him I went obnoxious as hell, but so smart. And I – you know, ended up interacting with him over the years, and he is who he is.

But even before – you know, if you wanted to do a conspiracy theory, I would say that Travis created the pandemic because about a year and a half ago, almost two years ago, he started creating this business about ghost kitchens for major brands. So you would order food from PF Changs, but it wasn't coming from PF Changs down the street from you. It was coming from a central kitchen that only was making the food for delivery. It's become very big, ghost kitchens is a huge business right now. And that's what he invested in. And now we're relying on ghost kitchens for a lot of our meals.

I'll set you free.

LP: That's amazing.

TC: It's been fun. I hope this wasn't too rambling, but it was because I know it is every time.

LP: No, I think it was beautiful, and I think that people always benefit from the insight, and I know I benefit from the insight. And I love talking to you, and I love hearing you talk. So thank you very, very much.

TC: My pleasure. Have a wonderful day.

LP: You too. Be well.

TC: OK. Bye-bye.

Ted Cohen

Consultant, Advisor, Board Member & Consigliere to some of the most innovative digital entertainment companies on this planet.

Greatest Hits

Wondering where to start or where to go next? Check out some of our most-listened-to episodes.